Irving Sanchez III supports the African American Burial Ground and Remembering Project and believes that the people laid to rest years ago in the forgotten cemeteries are worth being recognized and remembered.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

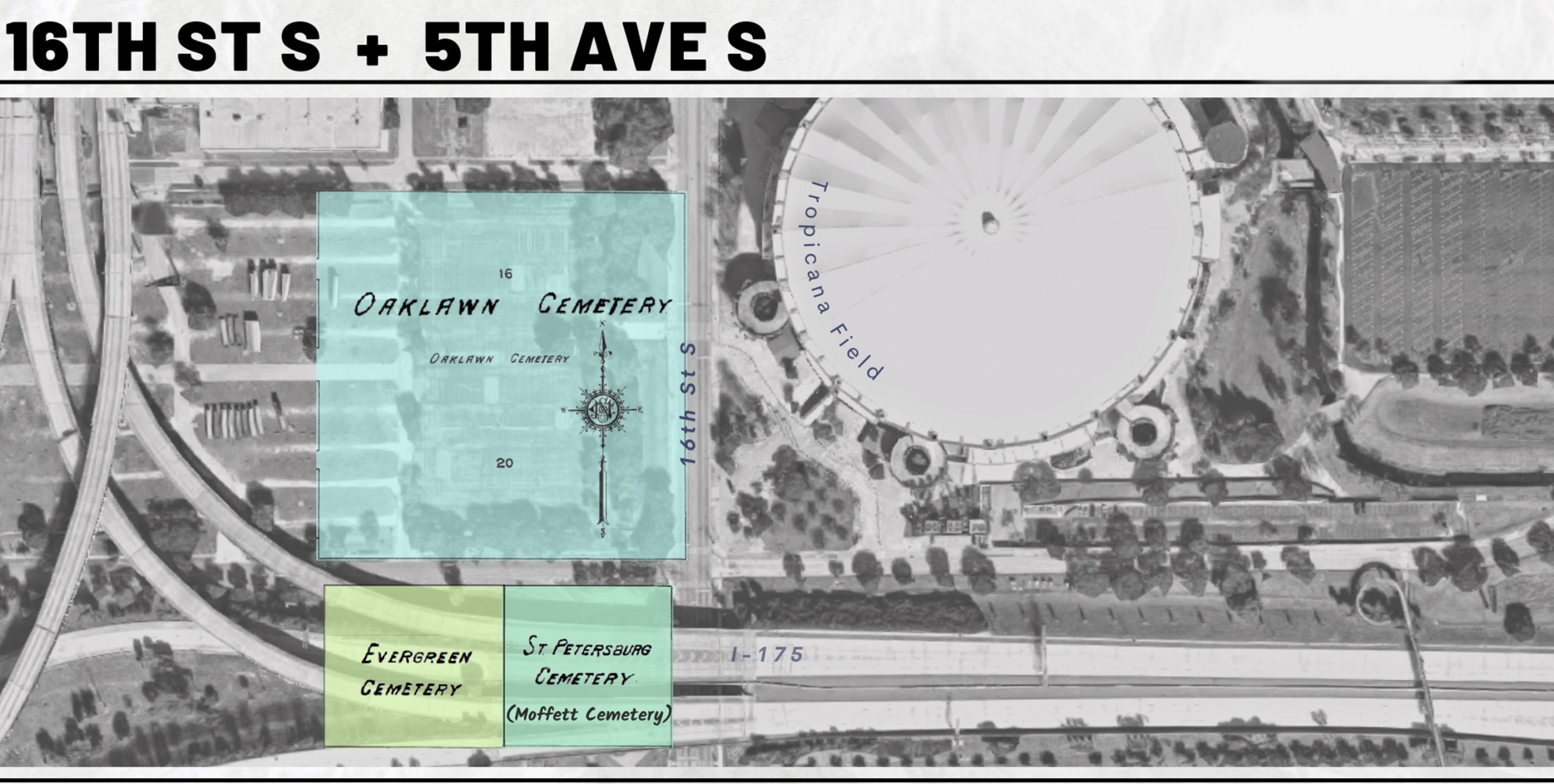

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (found beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Irving Sanchez III

For a good portion of his life, Irving Sanchez III has been in the business of seeing people off into the afterlife. Born and raised in the Midtown area near Jordan Park, he returned in 2014 and became the owner of Sanchez Rehobeth Funeral Home and Cremation Services after moving away from St. Pete.

His aunt, Jessie Marie Calhoun, lived in the Gas Plant area on Third Avenue off 16th Street South. She purchased the Williams Funeral Home on Ninth Avenue and 22nd Street South, and his father, Irving Sanchez, Jr., took it over from her in the 1950s, when it became Sanchez Arch Royal Funeral Home, later Sanchez and Son.

“She was married to a gentleman named R.C. Calhoun, who was a builder,” Sanchez said of his aunt. “And he built a ton of houses right there in the Gas Plant area and churches.”

Sanchez would often spend time at his aunt’s house as a youngster. While in elementary school, he attended Immaculate Conception Catholic School and would be shuttled to his aunt’s home after school until his mom got off work from Perkins Elementary.

Since this was the early 1960s, some of the Black cemeteries by then were not in use, and Sanchez only recalls Lincoln cemetery.

“There was no Oaklawn; there was none of that when I came up,” he said. “I don’t think there was a cemetery, known as a cemetery, in any of that area as I grew up. Everybody that was African American went to Lincoln. Everybody.”

Sanchez remembers the specific burial practices and rituals performed in the community back then.

“Everybody pretty much did the same thing,” he said. “Somebody passed, we picked them up, they were embalmed and prepared for a funeral. Typically, the funeral either went to the church—mostly went to the church—very few were chapel services. Going to the church was probably a must-do, you know.

Sanchez said cremation started getting popular in the 1970s, but before then, most African Americans “were buried in concrete liners, and they all went in a high plush cloth casket.”

There wasn’t much “mixing” in those days along racial lines, recalled Sanchez, when it came to preparations and services. But his father did quality work—including for those who had perished in car accidents, fires, or succumbed to cancer — and white families sometimes called upon him for his restorative abilities.

“My dad probably got called sometimes across racial lines because of the quality of his restorative work. A lot of funeral homes called him to come and do restorative work on their cases. That’s how he got to be known in more of the whiter circles because of that fact. But typically, he did what he did in his area, and they did what they did in theirs. Only when they had difficulty or issues would he be contacted.”

In those times, Black funeral homes were doing their own ambulance service. Sanchez said that as a boy, he had an important job that he always looked forward to.

“One of the things that I remember distinctly was whenever we got an ambulance call, my dad and whoever else was going to pick the body up — or the hurt person at that time — I was sitting in the middle seat, and my dad gave me the privilege to — whenever he was driving a hearse and he was ready to hit the siren, he gave me the responsibility of the one hitting the siren button!” he explained.

He noted that 99 percent of the time, they went to Mercy Hospital on 22nd Street South, and every now and then, going to segregated Mound Park, which is now Bayfront.

At first, young Sanchez started by hitting the siren and washing the whitewall tires. He became meticulous about the care that properly goes into washing the tires, which continues with his employees to this day.

“I mean, I could wash two cars –two cars — in 15 minutes, all right… So, I literally grew up in the funeral business from the ground up. Every facet of this business, I have experienced it. So, people don’t understand why I’m so specific about things that I’m requiring them to do. But the simple fact of the matter is I have worked in your shoes. Everything that I’m asking you to do, I have done it.”

He stoutly believes such meticulousness applies to everything in the business, including embalming. It’s a work ethic he’s held on to for his entire career.

“You can’t come in here and you got the man’s collar of his shirt all wrinkled, or it’s not in his suit the right way, just not neat like it’s supposed to be,” Sanchez said. “I mean, my dad would drill me about that kind of stuff.”

Everyone was appropriately dressed for burial, and if the deceased’s family couldn’t afford a suit, Sanchez explained they would often help.

“If you didn’t have a shirt, we’ll get you a shirt,” he said. “Now, that’s not as routine now as it was then, but I can assure you, everybody that was being embalmed and dressed and had a funeral burial was in a shirt and tie [and] suit because if the family couldn’t afford it, we would go somewhere and get it.

Concerning parts of downtown where African-American bodies were buried and could still feasibly be there, Sanchez wonders if the old cemeteries could be recreated.

“If that’s not possible, with all that’s been done, and it’s paved over or what have you — if the area itself could be identified, wholly, then sure, there should be some monument or something, some representation that they were there,” he said.

“Because, I mean, to the core of the funeral business, and I’ve said this often, most people get caught up in the cars or the limos or the buildings at the funeral homes and who dressed them and all this kind of thing. But to the core of the business of what we do, the significance of it is to remember a life.”

If the space is to be memorialized, Sanchez thinks, then it should be family members should be responsible for the remembrance of a deceased person. Yet the passing years may have eroded the memories.

“We’re talking generations now, so probably most of the family is no longer there or doesn’t have any recollection because they didn’t know it was there either,” he pointed out. “[If] you don’t have family representation, then the powers that be, if they—I have to say this the right way — if they were shown, trained, informed, enlightened on the significance of why we have to remember, why we have to look back, then they would understand that there’s a concrete reason that we should not allow these people to be forgotten. Then they should take a stance and say, ‘Yes, we should do so.'”

The problem with that is, Sanchez said, with passing generations, there has been less and less of what he would call “good morals” and “good folkways.”

Sanchez said if one generation is not teaching the next about who they are and where they came from, then there is no wonder heritage is lost.

“I hate to even say this, but people nowadays probably care less about any history other than what’s going on right now because they don’t know any better. They weren’t trained to know. They weren’t trained to care. They weren’t trained to respect their elders.”

He contends that it’s an uphill battle to get the people who are in power today to say it’s important to look back and commemorate a generation that in and of itself may not have seemingly done much.

“All right, well, they weren’t attorneys, they didn’t have big homes, they didn’t have—they didn’t do anything significant in life, so why should we make the effort to commemorate them?” he said.

Although the powers that be may not think these ancestors laid to rest in erased burial grounds had significant lives, they managed to survive overt racism, Jim Crow St. Pete, lynchings, legalized racial discrimination and white supremacy, all while raising a generation of political leaders, educators, civil rights leaders and entrepreneurs.

Sanchez supports the African American Burial Ground and Remembering Project and believes that the people laid to rest years ago in the forgotten cemeteries are worth being recognized and remembered. If you can win that battle, he said, it would be a matter of relocating and safeguarding the new location.

Click here to explore an interactive exhibit about the project.

Julie Armstrong interviewed Mr. Irving Sanchez, III, on May 7, 2021.

Dear Frank

This article is informative and as you know based on the work being done by the USF African American Burial Ground Team. Additional information about the project and access to the work being done by the team is published at USF Digital Commons–https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/african_american_burial_grounds_ohp/

Any additional project inquiries may be directed to Dr. Antoinette Jackson, PI, USF African American Burial Ground Project Team, via the USF Heritage Research Lab (https://heritagelab.org/). Thank-you!