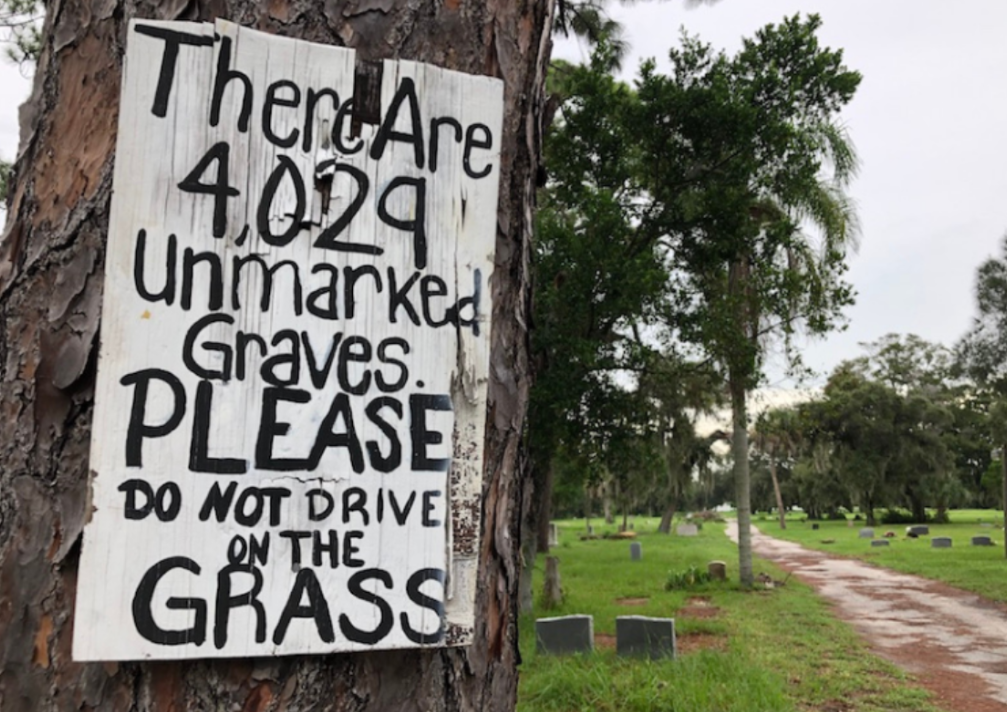

There are thousands of unmarked graves in Lincoln Cemetery, and since the topsoil moves over time, the graves with headstones could be a foot or two away from the actual vault.

BY WILL MICHAELS | Northeast Journal

ST. PETERSBURG — There has been much news about the Hines–Tampa Bay Rays proposal to build a new stadium in St. Petersburg, just southeast of Tropicana Field. It’s not just a stadium but a 20-year $6.5 billion proposal to redevelop the 86-acre area of the historic former Gas Plant neighborhood.

The proposed redevelopment calls for:

- 6,000 residential units, including 1,200 affordable and workforce units both on-and off-site

- a hotel

- 14,000 parking spaces

- A refurbished park along Booker Creek, which meanders through the site

- An entertainment venue

- Space for and a $10 million contribution to a new home for the Woodson African American Museum of Florida

Proponents of the development highlight anticipated job creation, economic stimulation of the surrounding area, and, most notably, a revival of the African-American sense of neighborhood devastated by previous development and failed promises and expectations.

View of the Historic Gas Plant neighborhood at its height. Some 500 households, nine churches, and 30 businesses were displaced by development. [Tampa Bay Times]

What is this latter proposal all about? The short answer is that Tropicana Field is also the site of an early city cemetery known as Oaklawn Cemetery.

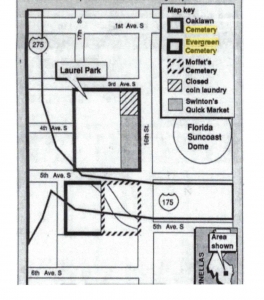

Among St. Petersburg’s first cemeteries were Moffett, Evergreen, and Oaklawn. Oaklawn Cemetery was located at what is now the west parking area at Tropicana Field, and Moffett and Evergreen were co-located just south of Oaklawn, largely beneath what is now I-175.

Moffett Cemetery was dedicated in 1888, the same year as the city’s founding, as a burial ground for Civil War veterans. Initially, the cemetery included both whites and African Americans. Two Civil War veterans are known to have been buried at Moffett (or adjacent Evergreen), but there may have been many others.

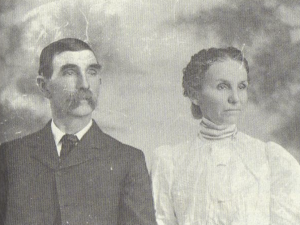

Moffett Cemetery was named after David Moffett, an early settler and St. Petersburg’s first mayor. Moffett himself is buried at Greenwood Cemetery, which was established in 1897 (Martin Luther King, Jr. Street and 11th Avenue South). After the establishment of Greenwood, Moffett became essentially a Black cemetery.

David Moffett and his wife, Janie. Moffett was the first mayor of St. Petersburg and established Moffett Cemetery (known initially as St. Petersburg Cemetery) in 1888. [St. Petersburg Museum of History]

Oaklawn Cemetery was north of the Moffett and Evergreen cemeteries, generally around the Tropicana parking area west of 16th Street South. Oaklawn was founded by the Independent Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF) and the local chapter of the Carpenters’ and Joiners’ Union of America in 1906. It was primarily for whites but included a segregated area for Black burials.

The cemetery also included Civil War veterans. Oaklawn Cemetery was also known as Grandberry Hill Cemetery. Evergreen Cemetery was acquired by S. D. (Samuel David) Harris in 1908. In 1910, Harris acquired Moffett. In 1913, the Carpenters’ and Joiners” Union conveyed their interest in Oaklawn Cemetery to the IOOF, and in 1917, the IOOF sold the cemetery to Harris.

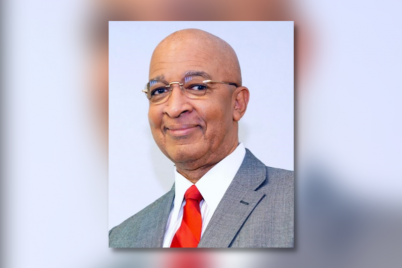

Undertaker and later juvenile judge Samuel D. Harris at one time owned Moffet, Evergreen, and Oaklawn cemeteries, image circa 1935.

Harris is a fascinating but little-known figure in early St. Petersburg history. Born 1866 in Sumter County, he relocated to Clearwater as a child with his parents. As a young man, Harris became a seaman and shipmaster. In 1894, he gave up his seaman’s life and became an orchardist. He next established a general merchandise and feed store in St. Petersburg in 1905.

In 1908, Harris became an undertaker after completing training in Macon, Ga., and passing the State Board of Health examination for embalmers. His funeral home was located at 674 Central Avenue. He continued in the undertaking profession until 1921 and then became a real estate investor. He also had a distinguished career in local politics and played an essential role in the creation of Pinellas County.

In 1921, Harris sold his undertaking business along with Oaklawn Cemetery to James M. Endicott and Sarah K. Cowen, owners of Endicott Funeral Home. Three years later, Endicott and Sarah Cowen Masterson sold all the unsold lots in Oaklawn, Evergreen, and Moffett cemeteries to Reginald H. Sumner, a prominent St. Petersburg contractor, real estate investor and county commissioner.

Among his business interests was Sumner Marble and Granite, Inc. He also owned Royal Palm Cemetery (First Avenue and 55th Street South), which is nearly adjacent to Lincoln Cemetery. Royal Palm was a historically white cemetery; Lincoln was established by Sumner in 1926 for African Americans. Why the name Lincoln was chosen for the cemetery is unknown. Likely, it was because President Lincoln was a hero to many African Americans.

Not-so-final resting places

On March 29, 1926, the City of St. Petersburg passed Ordinance No. 440-A. The title of this ordinance reads: “An ordinance declaring that public interest and public health demand the removal of bodies of deceased persons from Moffett, Evergreen, and Oakland cemeteries and be interred in Royal Palm Cemetery and the colored cemetery adjacent thereto, ordering the removal thereof at the [expense?] of the city…”

The ordinance goes on to state that the cemeteries concerned are poorly kept and “constantly used by the public as a passageway and are unsuitable for a resting place for the dead…” All persons were to be buried “in a location of equal dignity to the place now occupied by said bodies… and in a manner in keeping with the situation in life of said deceased persons then living.”

The “colored cemetery” was not referred to as Lincoln Cemetery in the ordinance and was perhaps unnamed at the time.

Another reason for closing the cemeteries and relocating the burials was that doing so would open up Fourth and Sixth Avenues South and “greatly” clear up “thoroughfares on the south side.” Subsequently, a new “Bay to Bay” street was opened on Fifth Avenue South, relieving congestion on Central Avenue.

Fifty burials were removed from Evergreen Cemetery to facilitate the roadway in 1926. The following year, 86 unknown persons were removed from Moffett Cemetery and reinterred in Lincoln.

For unknown reasons, only a portion of those interred at the three cemeteries were removed immediately after the 1926 ordinance. The grounds of Moffett Cemetery were improved, and as late as 1953, people were still buried there.

In June 1953, McRae Funeral Home put out a plea for those with relatives buried there to make arrangements for them to be relocated, as a youth center for African Americans was planned for the site. In 1958, approximately 225 burials were relocated from Evergreen to make way for an apartment complex.

Ownership of Lincoln Cemetery was transferred from Sumner to McRae Funeral Home in 1957. In 1958, approximately another 150 bodies were moved from Moffett and/or Evergreen Cemeteries to Lincoln. In 1976, a few human remains were uncovered during the construction of I-275 in the vicinity of Evergreen.

Rev. Basha Jordan Jr. at Lincoln Cemetery visiting family members. Among those buried are Jordan’s grandfather, Elder Jordan Sr., his wife Mary Frances, their six-year-old daughter Anita and son Elder Jordan. Jr. Elder Jordan Sr. was formerly enslaved and became a prominent businessman. [The Gabber]

In 1967, St. Petersburg’s city boundaries were changed to exclude land occupied by Lincoln Cemetery and adjacent areas, and the land was then annexed by Gulfport. This action was triggered by a rezoning application filed to permit a trailer park on 16 acres of land east of Lincoln.

Dr. J. C. Benefield, a former St. Petersburg city council member, owned the land. Rather than accommodate the rezoning request, the St. Petersburg city manager recommended “de-annexing” the property to Gulfport, stating it would be difficult and expensive for the City of St. Petersburg to provide services to the parcel. In newspaper accounts of the matter, there is no indication of discussion of the appropriateness of transferring jurisdiction over a cemetery, which was the resting place of primarily St. Petersburg residents, to another city.

Gulfport’s mayor did not learn of the proposal until the St. Petersburg City Council had already approved it. Gulfport City Council ultimately approved the transfer on a split vote, and only after Dr. Benefield had agreed to pay for sewer and waterline extensions. The dissenting members objected that the proposal was not “economical” and only part of the land would be taxable.

Lincoln Cemetery was sold to Sumner Marble and Granite in 1974 (Reginald Sumner himself had died in 1949). In 2009, Sumner changed its company’s name to Lincoln Cemetery, Inc. In 2017, the cemetery was purchased by the Lincoln Cemetery Society, Inc., which was superseded by the Lincoln Cemetery Memorial Park Corp and finally superseded by the Lincoln Cemetery Society, Inc.

The society is operated by a board of eight Gulfport residents, with Vanessa Gray serving as president. Before acquisition by the Lincoln Cemetery Society, a perpetual care fund of $109,000 was depleted. The society also inherited a $30,000-plus debt to the city of Gulfport for prior maintenance, which has yet to be paid, and the society has struggled to maintain the cemetery primarily through volunteer service.

The society and the Gulfport Veterans of Foreign Wars have undertaken recent maintenance. The city no longer provides maintenance.

Dignity for Known and Unknown Burials

In 2018, Cardno Limited, an infrastructure and environmental services company, conducted a Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) survey to facilitate confirmation of any remaining graves under the Tropicana Field parking lots. The survey identified two possible graves and seven “areas of interest.” The survey report also noted that it is likely that there are also disarticulated human remains mixed within the soil that could not be detected through GPR.

Sign in Lincoln Cemetery requesting visitors not to drive on the grass due to unmarked graves. [Courtesy of Shelly Wilson]

Dr. Ralph Wimbish is among the many African-American community leaders buried at Lincoln Cemetery. He led efforts to desegregate Spa Beach, lunch counters and lodging for MLB players. [St. Petersburg Museum of History]

The African American Burial Ground Remembering Project (AABG) is based at the University of South Florida. Its mission is to collaborate with Tampa Bay African-American communities “to recover histories that were paved over.” The project is researching and collecting oral histories and telling the story of Oakland, Evergreen, and Moffett cemeteries.

The AABG is in the beginning phase of new genealogical research on Black cemeteries in St. Petersburg, including a master listing of those reported buried in those cemeteries. That effort is coordinated by Drew Smith, associate librarian at USF. He is seeking volunteers to examine early Pinellas County death certificates for people likely to have been buried at Oaklawn, Evergreen, and Moffett. Work on Lincoln Cemetery is planned to follow.

Ownership of Lincoln Cemetery has been in dispute since 2017. While the Lincoln Cemetery Society claims title to the property and has struggled to provide maintenance for the past few years, they have been inhibited from seeking grants as their title to the property is clouded. Greater Mount Zion AME Church also claims the title. Recently, the two parties have come together to try and resolve the matter.

Gray, president of the Lincoln Cemetery Society, and Rev. Clarence A. Williams of Greater Mt. Zion AME have recently discussed how the title to Lincoln can be resolved and how the two organizations can work together. She said she is “very excited that we can come to a resolution that’s good for Lincoln.”

Wanda Stuart digging through burial records to find her stepfather’s whereabouts with Vanessa Gray this past June.

Pastor Williams stated, “Vanessa Gray has done a wonderful job trying to maintain Lincoln Cemetery. She has taken on a monumental task and poured her heart into this work. She reached out to me about this sacred space, and we feel that we can come together and work something out. We are looking at a new oversight board that can develop the necessary resources to maintain the cemetery. This is not just a local matter. This is part of a larger, national effort to restore and honor African American cemeteries.”

These hopeful developments may bring needed dignity to those buried at Oakland, Evergreen, Moffett — and particularly to the unknown burials at Lincoln Cemetery — and healing to their families and descendants.

This article was originally published in the Northeast Journal on Nov. 21.

Will Michaels is a former director of the St. Petersburg Museum of History and the author of “The Making of St. Petersburg” and “The Hidden History of St. Petersburg.” Reach him at wmichaels2222@gmail.com.

Will Michaels is a former director of the St. Petersburg Museum of History and the author of “The Making of St. Petersburg” and “The Hidden History of St. Petersburg.” Reach him at wmichaels2222@gmail.com.

Will Michaels during the 6/13/23 City of St. Petersburg Historic Preservation Commission Mtg as a Commission Member offered to Meet with Lincoln Cemetery Descendant Leaders, Sierra Clark & Tomeeka Wright who spoke at the Mtg. A Week later Will Met with a Lincoln Cemetery Descendant Leader to assist with the Honoring of All 7,000 People Resting at Lincoln Cemetery.