By Jacqueline Hubbard

After Reconstruction, the United States Supreme Court on May 18, 1896, issued an opinion in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson. Most historians regard this case as laying the legal foundation for the separation of races as being constitutional in the United States, as long as the separation was “equal.”

Plessy v. Ferguson dealt with the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment’s (1868) equal-protection clause, which prohibits the states from denying “equal protection of the laws” to any person within their jurisdictions. Although the majority opinion did not contain the phrase “separate but equal,” it gave sanction to laws designed to achieve racial segregation by means of separate and equal public facilities and services for African Americans and whites.

It served as the controlling judicial precedent in America until it was overturned by the Supreme Court in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, in 1954. Brown resulted in the desegregation of American public schools.

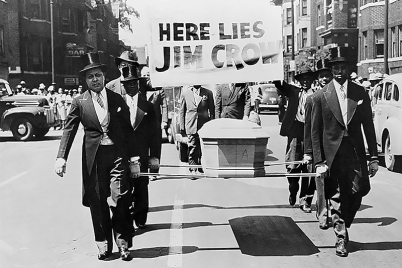

The end result of Plessy was a systematic wave of Black Codes, discrimination in every form and the institutionalism of Jim Crow. The legality of this system of segregation lasted more than 60 years.

Its precursor was a wave of racial terrorism, particularly in the southern and mid-western states, the re-emergence of the Ku Klux Klan and the abominable act of lynching that claimed nearly 5,000 black lives.

The case originated in 1892 as a challenge to Louisiana’s Separate Car Act (1890) that required that all railroads operating in the state provide “equal but separate accommodations” for white and African-American passengers and prohibited passengers from entering accommodations other than those to which they had been assigned.

In 1891, a group in New Orleans hired an attorney, Albion Tourgée, to contest the law. The plaintiff was Homer Plessy, who was seven-eighths white and one-eighth African American. Plessy purchased a rail ticket and took a seat in a car reserved for whites. After refusing to move to a car for African Americans, he was arrested.

At Plessy’s trial in U.S. District Court, Judge John H. Ferguson held the act was constitutional. The Louisiana Supreme Court affirmed Judge Ferguson’s ruling and the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari and rendered its decision.

The Supreme Court relied upon in the Civil Rights Cases of 1883, which found that racial discrimination against African Americans in public accommodations “imposes no badge of slavery or involuntary servitude…but at most infringes rights which are protected from State aggression by the 14th Amendment.”

Only one judge disagreed with the majority opinion in Plessy, Associate Justice John Marshall Harlan. Judge Harlan argued the act was unconstitutional because it regulated civil rights on the basis of race. Judge Harlan wrote: “Our Constitution is color-blind.”

Later cases have proven that the United States Constitution, especially after the “Civil War Amendments.” is, indeed, color blind. It is a constant struggle to keep it that way.

Historically, black Americans have relied upon legislation such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 to preserve this constitutional argument. Under our governmental system, we have three co-equal branches of government: the President’s Executive Branch; the Congress and the Judiciary.

In order to preserve the ability of each branch to check the other, the system depends upon its citizens exercising their right to vote. Voters elect the president and the Senate. The president nominates the justices for the Supreme Court and the Senate decides whether to confirm the president’s nominees.

Supreme Court Justices serve for life. The people elect the president and congress. In order to preserve the integrity of the system, first, all people need to vote, and second, the votes need to be fairly counted without interference.

The more we vote, the harder it is to interfere with the integrity of the outcome. Don’t ever take your right to vote for granted. Use it.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.