Outside of a Black church in Little Rock, Ark., 1935

BY REV. PIERRE LOOMIS WILLIAMS, Contributor

Come unto me, all who are labor and are heavy-laden, and I will give you rest. (Matthew 11:28)

In the days of the past, the clarion call and mission of the Black church was two-fold: it served as a beacon of hope for the lost-soul seeking grace and mercy, and also as an oasis for all issues affecting the community. The Black church served as a voice in the wilderness, crying out that equality and justice belonged to all persons, despite race, social status, or lived experience.

The church operated as 24-hour, full-service institutions, affecting change spiritually, intellectually, emotionally, and socially. People from all walks of life recognized that the Black church was a place where needs were met and issues addressed when resources were exhausted.

The Black minister preached a transformative message of salvation and served as a community representative and social activist, preaching a message of social change, equality, and unconditional love.

Rev. Pierre Loomis Williams

While most Black ministers were not formally educated in the pre-Civil Rights era, the message of the Declaration of Independence presented a complex challenge for the Black church: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these life, liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

Considering the liberty of the children of Israel and the liberty of African slaves, liberty has been the crux of the Black church. Consider the words of a familiar Black spiritual: “And before I’ll be a slave, I’ll be buried in my grave, and go home to my Lord and be free.”

Now, in our contemporary society where the Black church has become so focused on preaching messages regarding the attainment of economic success and personal prosperity, has it begun to lose sight of its foundational calling, rooted in a message of salvation with the promotion of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness?

In the days of the Civil Rights agenda, the Black church fulfilled the words of Malcolm X (how fascinating, the use of a minister of Islam in an exposition of the Black church) “by any means necessary.” The Black minister proclaimed a message of hope and change within all persons (regardless of race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, educational attainment, or family background) so all could find solace, and the people of the church served the direct human needs of the public from meals to medicine and from housing to hope.

The Black church once connected to society’s ills and developed a sense of responsibility in fighting those troubles. Whether it required a Sunday morning message or civil disobedience, the Black church accepted its role in genuine social change and community transformation.

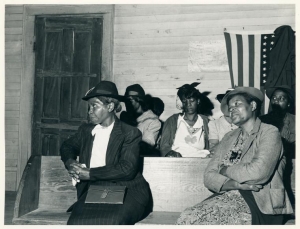

Church goers in Heard County, Ga., 1941

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., an eminent prophetic voice in the reform of American society, once wrote in his 1963 “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” that “In the midst of blatant injustices inflicted upon the Negro, I have watched white churches stand on the sideline and merely mouth pious irrelevancies and sanctimonious trivialities.”

Yet, in this post-modern culture, it is no longer exclusively white churches on the sideline of truth and justice, allowing the struggles of underrepresented or oppressed groups to perpetuate, but it is also the churches filled with those underrepresented groups, allowing the perpetuation of injustice and inequality.

The message of the cross as the changing force of all aspects of life has become silenced by the message of the dollar. The Black church, a place where people came to receive whole life empowerment, has now become a wealth workshop and capital industry. Accepting that financial opulence is a component, and some would contend a derivative of the gospel message, it should not serve as the nucleus of the message.

Furthermore, accepting that our culture’s educational, economic, and ethnic façade is changing, the essence of social problems remains the same — inequality and non-access for oppressed populations. Thus, it is the responsibility of the Black church to not compromise the message of the gospel with a message of capitalism.

Therefore, the question becomes, what can the Black church do to recapture its identity as a city of refuge and a beacon of hope? Above all else, it must return to its first love: the social, compassionate, and liberating gospel of Jesus Christ. It must stand on the teachings of Jesus despite the pressure and magnetism of contemporary societal fads to mitigate the work of the cross for the influx of capital expansion.

The Black church must focus on living the commission of compassion while also continuing to preach a message of freedom, justice, equality, and hope for all persons from all walks of life. Ernest Hemingway, an American writer and scholar, once penned, “Never mistake motion for action.”

In the same essence, the Black church must never mistake the Sunday morning motions as the spiritual, intellectual, emotional, physical, and social actions that must be taken Monday through Saturday for the full service of all humankind.

The mere act of preaching motivates the soul, and the melodies of song enliven the emotion; ye,t motivation and revitalizing are not enough for debt to be eliminated, graduation rates to rise, and affordable housing and healthcare to be attained — all parts of the present social crisis.

As part of the Black church, parishioners must recapture their identity in this society; only then will it serve as a collective utility of social transformation and positive change.