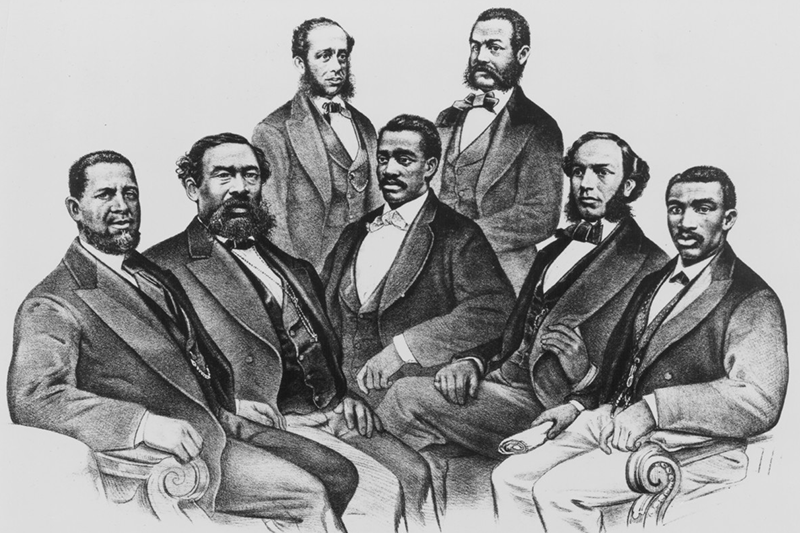

Portrait of the first Black senator, H. M. Revels of Mississippi (far left) and Black representatives of Congress during the Reconstruction Era, circa 1870-1875

By Jacqueline Hubbard, Esq., ASALH President

Imagine the circumstance that existed after the Civil War:

- The enslaved were freed

- The Southern slave states that had seceded from the Union and formed the Confederacy had lost the war

- Nearly 180,000 Black armed Union Troops, who knew how to use guns, had fought with the Union in the War

- The institution of forced, enslaved free labor had ended

- The plantations were dying out

- The rich plantation owners were becoming impoverished

Plantations could not stay profitable without free labor to tend their cotton, rice, indigo, tobacco and other crops. There was confusion, resentment, bitterness and deep racial hatred throughout the South.

As many as 620,000 soldiers had been killed in an era when medicine and surgery were in their infancy. An equivalent proportion of today’s population would be six million people, according to historian Drew Gilpin Faust in “This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War.”

The remaining majority of non-plantation owning whites were poor and illiterate. Hatred and resentment ruled the South. Instead of blaming their poor warrior skills and lack of preparation for war, the Confederates blamed their defeat on the “turncoat enslaved” and the “overwhelming military might of the Union Army.”

Yet, their deepest hatred was for the emancipated Blacks who told the lie on enslavement: it was a barbaric, cruel institution that destroyed families, exerted full dominion over the enslaved, who had no rights, and served at the mercy of the slave owner, who was often heartless, sadistic and mean-spirited.

However, the Civil War allowed Black people the opportunity to resist enslavement en masse, escape and fight for their freedom. This made the experience of the Black Union soldier unique. According to Faust, “the conflict was a moment for both divine and human retribution, as well as an opportunity to become the agent rather than the victim of violence.”

How did the victorious North decide how to handle this enormous challenge? Not since the founding of the Union had so pressing of a problem confronted the nation. First in importance were the Civil War Amendments.

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States Constitution set forth four fundamental Constitutional guarantees to the formerly enslaved:

(1) the abolition of slavery

(2) equal protection under the laws of the United States

(3) entitlement to due process under the laws of the United States

(4) the right to vote

Second, were the Reconstruction Acts establishing the Freedman’s Bureau. Third, was the use of Union troops to enforce the newly enacted rights among a group of Southerners who had lost their civil rights, including the right to vote if they had participated in the South’s insurrection.

According to W.E.B. DuBois in his seminal work “Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880,” the effort at Reconstruction was a huge undertaking, partly because of the enormous size of the Black population and partly because of the massive resistance to full citizenship for Black people, especially the resistance to the right to vote.

As to sheer population numbers, DuBois noted that before 1830, the black population had passed the “two million mark helped by the increased importations just before 1808, and the illicit smuggling up until 1820.” In 1850, Blacks reached 3,638,808 and before the Civil War stood at 4,441,830.

Reconstruction was hard-fought and lasted for a relatively short period of time. For the first time in America, all Black men could vote. Blacks were elected to high office, even to the United States Congress. Union Troops came to the South to protect the ballot and with the Freedman’s Bureau, ensuring the right to vote and the building of the first public schools for Black Americans.

All efforts were met with severe anti-Black violence. Teachers, doctors, dentists, lawyers, writers, artists, the Black press, skilled artisans and craftsmen began to bring their talents to fruition. Never again to be totally suppressed.

Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) began to be built. Prosecution of the Ku Klux Klan was enforced by President Ulysses S. Grant, who instituted the Office of the United States Attorney to fight them and actively supported Reconstruction and voting rights.

It was a battle fought but ultimately — some would argue — lost for the soul of America. Violent resistance was fierce. DuBois summed up the situation when he wrote: “How two theories of the future of America clashed and blended just after the Civil War: the one was abolition-democracy based on freedom, intelligence and power for all men; the other was the industry for private profit directed by an autocracy determined at any price to amass wealth and power. The uncomprehending resistance of the South, and the pressure of Black folks, made these two thoughts uneasy and temporary allies.”

By 1876, after the compromise election of President Rutherford Hayes, Reconstruction began to end. The protection of the vote by Union Troops was withdrawn, insurrectionists were again permitted to vote, the Ku Klux Klan re-emerged, Black Codes that openly discriminated against Black Americans, and rigidly enforced segregation became the law in the South.

Without the support of the North, the universal right to vote gradually disappeared and disenfranchisement became the norm through technical requirements most Black Americans could not meet, such as poll taxes.

Open violence against those who attempted to vote became widespread. A reign of terror against Black Americans began in earnest. The Equal Justice Initiative, located in Montgomery, Ala., has counted 4,400 terror lynchings between 1870 and 1950. This violent reaction to Reconstruction did not begin to dissipate until the 1950s when the Civil Rights struggle began.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.