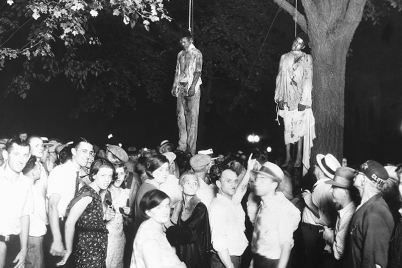

With more than 1,300 miles of coastline, Black Floridians had to contend with the issue of segregation on public beaches as well as lunch counters, schools, public transportation, and movie theater. Photo courtesy of Florida Memory

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

SARASOTA — The Sarasota African American Cultural Coalition (SAACC) held a free online history course to discuss the history of segregation of Florida’s biggest draw: its beaches. The discussion dissected some of the landmark protests over the state’s segregated beaches in the 1950s and 60s.

Vickie Oldham, president of the SAACC, said Sarasota’s history of desegregating Lido beach is one of the most important civil rights stories coming out of the city.

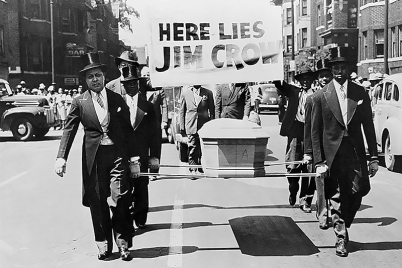

Confrontation between integrationists and segregationists at a whites-only beach in St. Augustine, Fla. Photo courtesy of Florida Memory

“The work of Newtown activists in organizing these caravans and ‘wade-ins,’ they are listed in the U.S. Civil Rights Trail,” she said.

Historian at the State Archives of Florida, Dr. Josh Goodman, said the state’s unique geography ensured beaches would become a prominent “battleground” in defeating Jim Crow laws during the Civil Rights Movement. In the days of segregation, most of the beaches were reserved for whites, and if African Americans had any beach access at all, it had to be completely separate.

“Gaining that access generally required a protracted fight, and sometimes it was not possible at all to obtain public beach access,” he said.

Goodman said that Black Americans found ways to circumvent and later openly resist this form of segregation.

At the turn of the 20th century, industrialist Henry Flagler established one of the first private Black beaches on Florida’s east coast, Manhattan Beach. Initially purposed as a relaxation spot for the Black workers at his Continental Hotel near Jacksonville, it soon became a tourist attraction for African-American families from all over the Southeast.

“Black labor unions, church congregations, scout troops, all kinds of African-Americans groups were coming to this area,” Goodman noted.

In the 1930s, American Beach, just north of Jacksonville, was established by a Black business — the Afro-American Life Insurance Company. Though it also began as a perk for company employees, it wound up establishing an entire community there. Black families purchased land in that area, and new Black businesses emerged just to serve the growing number of tourists.

In time, Florida’s Black residents began to take on Jim Crow more directly. They participated in nonviolent “wade-ins” in Miami as far back as the 1940s to gain access to beaches that were off-limits to them. They simply waded into the water of white beaches in protest. In time, such protests would take place in Sarasota.

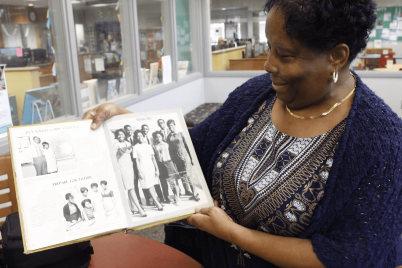

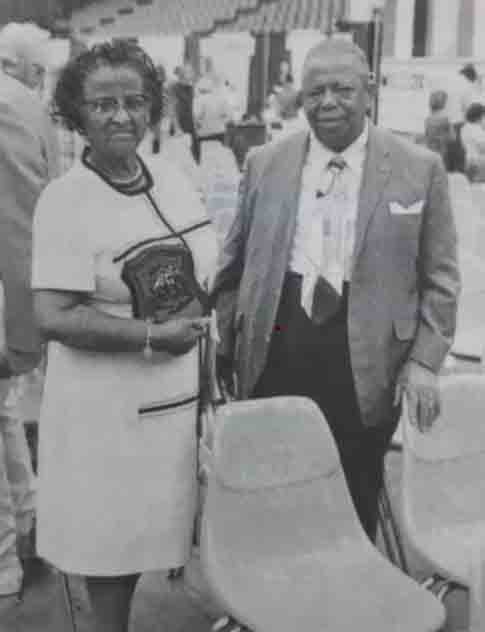

In 1951, Newtown business owner Mary Emma Jones requested a “colored” beach at a Sarasota Board of County Commission meeting. Mary Emma Jones is pictured here with her husband Jack Jones. Photo courtesy of Vickie Oldham

Initially, Sarasota’s Black residents wanted a public beach facility established for them. By the early 1950s, local entrepreneur and Newtown resident Mary Emma Jones made such a request at the Manatee County Commission meeting.

The county formed a committee to mull over this problem, but ultimately nothing got accomplished. By 1955, Goodman said, the county was considering selling its public beach facilities to private owners. As this was just after the Brown v. Topeka Board of Education decision, private companies would then be responsible for setting their own rules and regulations. However, the governor made it clear that he would not support such actions.

Civil rights activists found a sturdier platform when “separate but equal” was judged to be unconstitutional not only in classrooms but in places such as public buildings, parks, golf courses, and even swimming pools and beaches.

“Black activists trying to integrate facilities like beaches and lunch counters and things like this, they didn’t just have morality on their side anymore,” Goodman noted. “They now had the law on their side.”

As Sarasota officials feared equal access to their beaches would decrease their attractiveness to white tourists, they proposed establishing a public pool in Newtown instead of allowing beach access. Black residents, however, were adamant in getting access — among them Neil Humphrey, Sr., then-president of NAACP Sarasota.

Humphrey and other local leaders began organizing caravans to go from Newtown to Lido Beach, and later other beaches, to wade in, “or at least just sit on the beach and occupy the beach as citizens of Sarasota County exercising their rights to be in that space as taxpayers and members of the public,” Goodman explained.

Though they were peacefully demonstrating, the Black beachgoers not only weathered curses hurled at them but rocks and bottles. NAACP leaders instructed them to stay calm in the face of it all but to stand their ground. One demonstrator would go on to say years later that she believed “God made all of that water, and I should have access to it, too.”

As Sarasota officials feared equal access to their beaches would decrease their attractiveness to white tourists, they proposed establishing the above public pool in Newtown instead of allowing beach access. Photo courtesy of Vickie Oldham

Odessa Butler participated in a “wade-in” when her mother was the NAACP Sarasota president. She remembered her mother underscoring to the caravan and “wade-in” participants that there would be no violence, taking her cue from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

“We were to be quiet,” Butler said. “We were to act like we knew what we were doing and where we were going.”

The caravans would line up on Orange Avenue after church, she recalled. Her mother one day asked the sheriff if he would provide a police escort, and though he didn’t say yes or no immediately, in time, police officers on motorcycles would escort them on the way to the beach. Once there, they were fair game to the myriad jeers from whites.

“We were taunted, words were said,” she remembered. “It was not pleasant, but because we were taught nonviolence, everybody acted very well. Very well. And then when we got home, we talked about how mad we were!”

Looking covertly to deter demonstrators, in 1956, the city commission passed an ordinance stating that any time there were members of two or more races on the beach, the police had not only the right but the obligation to close that beach down. Despite this, the caravans trundled on, Goodman pointed out.

“At no point, in those days at least, did the city commission ever revoke this emergency ordinance,” he said. “Over time, quietly and informally, the city just stopped enforcing the ordinance eventually — but never came out and said that they recognized the right of African Americans to use the beach.”

The SAACC recognizes the route taken by the caravans in a trolley stop tour, which winds along the same streets and makes stops at notable places, such as the location of Neil Humphrey’s drug store.

Renee Gilmore, executive producer and host of ABC7’s “Empowering Voices,” a political affairs TV program, is the great-granddaughter of Mary Emma Jones. Even as a child, Gilmore said she knew Jones was “pretty special” and described her as a multi-tasker. Jones not only operated businesses like a taxi service and a restaurant, but she led the Colored Women’s Civic Club in Newtown.

“It just fills my heart to hear my great grandmother’s name called and to know that between my great grandmother and Ms. Butler’s mother and Ms. Butler herself, these kinds of people who truly were in their own minds just regular people standing up for all of us,” she said. “I am standing on shoulders.”

Oldham said the coalition aims to open the Museum of African American History and Culture, which will showcase exhibitions by Black artists, host programs, and focus on historical events such as the fight to integrate Sarasota beaches.

The center will initially be housed in the historic Leonard Reid home, but plans are to relocate it to a spacious 17,000-square foot facility at some point. The beach desegregation story will be told in a permanent exhibit.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com