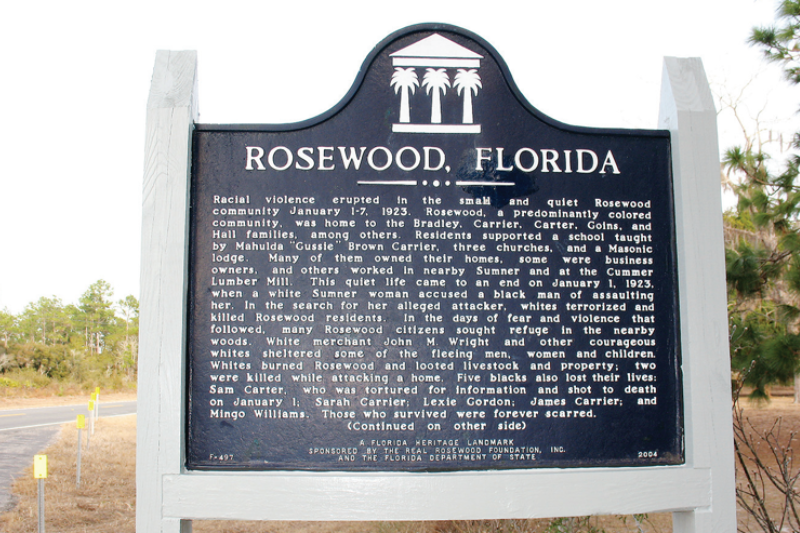

This past January marked the 100th anniversary of the Rosewood tragedy, a racially motivated massacre of Black people and the fiery destruction of a predominantly Black town in Levy County.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

CLEARWATER – This past January marked the 100th anniversary of the Rosewood tragedy, a racially motivated massacre of Black people and the fiery destruction of a predominantly Black town in Levy County. As part of the Florida Humanities series, “A Florida Talks Event,” Dr. Vincent Adejumo held a lecture at Pinellas County African American History Museum.

Before its destruction, Rosewood was located near Cedar Key. Adejumo called the abandoned town an “eerie place.” “You can almost feel the souls that were killed there,” he noted.

Dr. Vincent Adejumo, University of Florida lecturer in African American Studies

The years during WWI saw Black lives terrorized by a renewed racism, Adejumo explained, which was fostered in part by the policies of President Woodrow Wilson’s administration. The president allowed his cabinet members to pursue policies that disenfranchised African Americans. Furthermore, southern members of Congress feared that Black veterans — once they had fought for the flag — would return from the war with the notion that their political rights must be respected.

In cities and towns around the country, white mobs, often in alliance with police officials, denied Blacks the rights and privileges afforded to whites. Many whites lashed out at African Americans during and after the war, often in violent ways, which included lynchings.

A cabin burned in Rosewood on January 4, 1923.

With the 1915 premiere of the film “The Birth of a Nation,” which glorified the Ku Klux Klan, a renewed interest in the KKK swept the South and beyond. Southern newspapers also added to white fears by publishing almost a daily litany of alleged racial attacks and rapes by Black men against white women.

This appealed to readers who had a “fascination with the violent and the grotesque,” Adejumo, a full-time lecturer in the African American Studies Department at the University of Florida.

In 1920, members of the KKK attacked the Black town of Ocoee, Fla., in Orange County. Over 30 Black people were killed while all remaining African Americans fled the town, which remained all white until the 1980s. Two years later, race relations took another terrible turn when a white schoolteacher in Perry, Fla., was allegedly murdered by an escaped Black convict. White residents discovered her badly beaten body about one month before the Rosewood massacre. Though they were not formally implicated in the crime, Black men were shot and hanged in response.

The Levy County sheriff Bob Walker, holds a shotgun allegedly used by Sylvester, a Black resident of Rosewood, to shoot and kill two deputized white men who were at his door.

Rosewood, founded in 1870, was a predominantly Black town by the turn of the 20th century. By 1920, the residents of Rosewood were primarily self-sufficient, as the town had churches, a school, a large Masonic Hall, a turpentine mill, a sugar cane mill and even a baseball team, the Rosewood Sluggers.

It also had two general stores, one of which was white-owned. Some land-owning Black families had pianos, organs and other symbols of middle-class prosperity. There were rising racial tensions, as the events in Ocoee and Perry were still fresh in people’s minds and an escalating resentment toward African Americans and their upward mobility.

“There was a strong Civil Rights Movement in Florida between 1910 and 1920,” Adejumo said. “That’s why we see these massacres happening because it was a response — they didn’t care nothing about the accusations!”

After Fannie Taylor, a white woman in nearby Sumner, Fla., claimed she was assaulted by a Black man, a group of white men descended on Rosewood in Jan. 1923. James Taylor, a foreman at Cummer & Sons mill and husband of Fannie, assembled a vicious mob and tracking dogs.

“The white community became enraged at the alleged abuse of a white woman by a Black man — again, alleged,” Adejumo said.

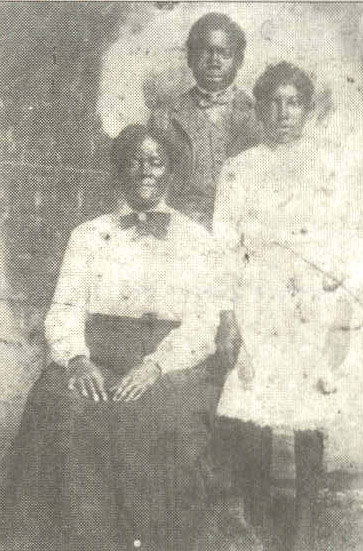

Taylor enlisted help from members of the KKK, who had recently held a large rally in Gainesville, about 50 miles away. Four or five hundred Klansmen combed the woods behind the Taylors’ home in Sumner, looking for a suspect. Suspicion soon fell on Jesse Hunter, a Black man who had supposedly just escaped from a chain gang. A sheriff’s posse searched for Hunter, but when no trace of him could be found, the posse turned into a lynch mob and seized Sam Carter, a local blacksmith who had supposedly given aid to Hunter.

They riddled him with bullets and hanged his mutilated body from a tree to intimidate Black people, Adejumo said. When the posse returned to Rosewood, they found Aaron Carrier and “angrily pulled him out of bed, roped him, tied him behind a car and dragged him to Sumner, cursing and ranting all the way,” Adejumo said.

Sarah Carrier (left), Sylvester Carrier (standing) and his sister Willie Carrier (right), taken around 1910

“They cut him loose, stomped him, kicked him and spat on him,” he said.

The Levy County sheriff, Robert Walker, then put Carrier in his car and drove him 55 miles to Gainesville, where he begged his friend Sheriff Ramsey to put Carrier up in his jail and not disclose to anyone that he was being held there. On Feb. 1923. a special grand jury investigated the Rosewood massacre, as white mobs burned almost every structure in the town. Black people hid in nearby swamps as the roving mobs terrorized the town.

After 25 white and a rumored eight Black witnesses testified, the jurists reported that they could find no evidence on which to base any indictments. No arrests were made. Though eight deaths were officially accounted for (six Black and two white), the actual loss of life was almost certainly much higher.

Black turpentine workers were encouraged to stay in Florida only after they became scarce.

The Black residents all ultimately fled Rosewood for other cities, as some even settled in St. Pete. Many lost touch with one another, never sharing the horrific stories with each other or their family members. Some had become so terrified that they changed their names to disassociate themselves entirely from the town.

In 1982, Gary Moore, a reporter from the then “St. Petersburg Times,” resurrected the history of Rosewood in a series of articles that brought national attention to the tragedy. The living survivors of the massacre, who were all in their 80s and 90s, then came forward and demanded restitution from Florida. This led to the passing of the Rosewood Compensation Bill, signed by then-Gov. Lawton Chiles in 1994, which awarded the survivors and their descendants a package of $2.1 million.

Rosewood today is part of Cedar Key and is 98 percent white, two percent mixed race and zero percent Black.