The Childs Park subdivision was platted in 1911 by Julius A. and Lysander D. Childs. The remainder of the neighborhood was platted in the teens, 1920s and 1940s by many persons.

BY JAMES SCHNUR | The Gabber

ST. PETERSBURG — Much of Gulfport’s eastern boundary along 49th Street abuts Childs Park. Generally, this St. Petersburg neighborhood spans from 5th Avenue South to 22nd Avenue, between U.S. Highway 19 and 49th Street.

Similar to how the label “South St. Pete” creates overbroad misperceptions, viewing Childs Park as a singular entity denies the diverse history of its neighborhoods.

Childs-free groves and farms

During the late 1800s, groves and farms in portions of western Childs Park had closer ties to Disston City (present-day Gulfport) than the small hamlet of St. Petersburg. Two early pathways connected agricultural lands with Gulfport’s waterfront.

An east-west dirt road that became Lakeview Avenue (22nd Avenue South) offered a corridor between Big Bayou and Disston City. Big Bayou’s “Pinellas” settlement, now the Driftwood neighborhood, existed before St. Petersburg.

Similarly, a north-south path that became Disston Avenue (49th Street) allowed growers to bring their goods to boats moored along Clam Bayou and present-day Gulfport Beach.

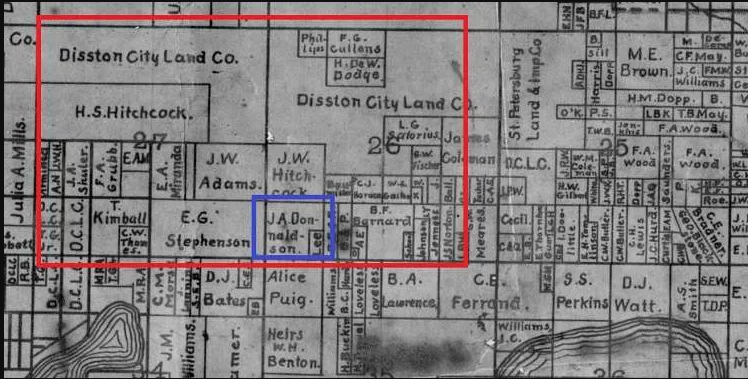

The red box on this 1902 map highlights landowners in the approximate boundaries of Childs Park. Lands once held by John Donaldson — the first Black landowner on the peninsula — appear in the small box. | Photo from Heritage Village

John Donaldson, a farmer and occasional mail carrier, acquired a 40-acre tract in the area. Donaldson’s children attended school in Disston City. He gained respect for his syrup, farm products and negotiating skills.

Donaldson became the first Black landowner on the Pinellas peninsula. He arrived more than a decade before the Orange Belt Railway reached the village of St. Petersburg in 1888.

Streetcars, ostriches, and a field of dreams

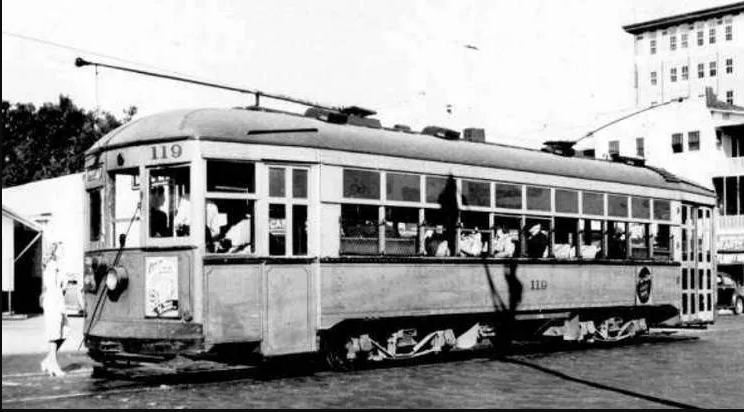

The streetcar line’s completion in 1905 accelerated development. Shortly after J.F. Chase transformed the former Disston City into Veteran City, electric trolleys ran along Tangerine Avenue (18th Avenue South) to and from St. Petersburg. Early conductors often contended with wild horses, cattle, and razorback hogs.

Streetcars such as this one in St. Pete ran along 18th Avenue South to Gulfport. | Photo from Heritage Village

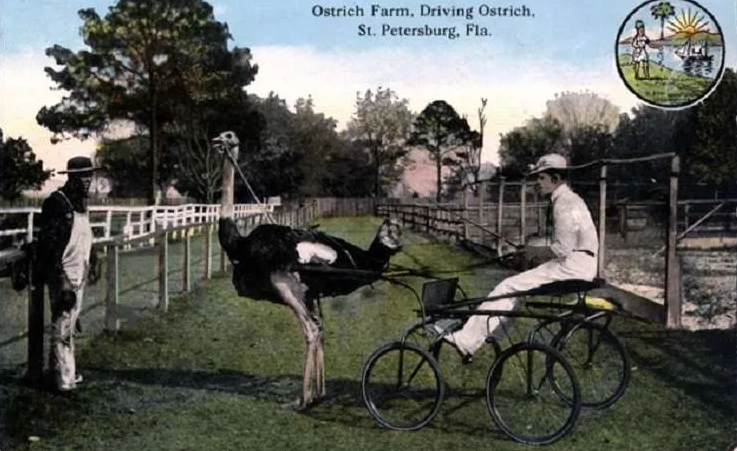

In 1908, Jerry Wells brought his Tampa ostrich farm to the area. He leased land slightly west of present-day Thurgood Marshall Fundamental Middle School along 18th Avenue. A trolley stop allowed people to travel to his St. Petersburg Ostrich Farm and Zoo to see more than 50 ostriches.

Visitors could watch daily ostrich races and interact with other animals for the cost of a nickel trolley fare and a dime (for children) or 15 cents (for adults). An April 1913 fire at Wells’s farm closed this attraction. By the 1930s, another St. Petersburg Alligator and Ostrich Farm flourished near Big Bayou.

The original St. Petersburg Ostrich Farm and Zoo opened in Childs Park in 1908. | Photo from USF Digital Collections

The St. Petersburg Saints sought a new baseball diamond in 1910. Their manager, Charles Clarence Symonette, negotiated a deal to move the Saints from a field near Mirror Lake to groves west of the Ostrich Farm. The Saints played their first game against the Tampa All-Cuban Stars at Symonette Field in September 1910.

A month after Symonette Field’s inaugural game, voters in Veteran City decided to incorporate their town as Gulfport. By that time, St. Petersburg had ambitions of claiming much of the land near the trolley line east of 49th Street.

The youthful years

Eugene B. Rowland grew crops on land he owned north of 18th Avenue, near 40th Street South. After streetcar service began, he turned some of his holdings into the Oak Park subdivision. By the time Rowland passed away in 1913, developers started carving lots out of fields west of 43rd Street, between 15th and 18th Avenues, creating the Forest Heights subdivision.

The Tampa and Gulf Coast Railroad reached St. Petersburg in 1914, following the current path of the Pinellas Trail. With the railroad and regular trolley service running through the area, St. Petersburg’s city limits expanded westward into unincorporated lands formerly associated with Disston City.

Childs’ neighborhood

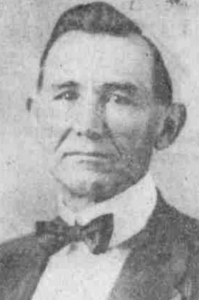

L.D. Childs, in 1920. | Photo from Google News Archive/Fair Use

Lysander Doolittle Childs moved to St. Petersburg in 1912 after wintering here for a few years. A western North Carolina native, he was born in 1866 at a settlement named for his family, Childsville. Now a ghost town, his family had established a sawmill and grist mill in that community.

Along with his older brother, Dr. Julius Arthur Childs (1858-1945), L.D. Childs began selling real estate. Additionally, Lysander’s son, Charles Albertus Childs (1899-1971), worked at the L.D. Childs & Sons office on Central Avenue.

Their firm marketed “Childs Park” properties northwest of the intersection of 22nd Avenue and 34th Street South. With some lots spanning more than a third of an acre, advertisements announced that they were “sufficient for a home with chicken ranch, garden, and fruit.”

More than Childs’s space

The “Childs Park” name encompasses an area much larger than the properties L.D. Childs sold. In addition to Oak Park and Forest Heights, other developments sprouted in the area. C.A. Harvey acquired 10 acres west of the original Ostrich Farm in February 1910. His holdings spanned between 18th and 22nd Avenues, near 42nd and 43rd Streets.

Harvey, the developer of the Bayboro Harbor area south of downtown St. Petersburg, turned this land into Boca “Ceiga” Heights. He misspelled “Ciega,” and “Boca Ceiga” remains the improperly spelled proper name for property platted in this area.

By late 1913, realtors proclaimed that sales in Fairmount Park would help St. Petersburg become “the Los Angeles of the East.” Fairmount Park boosted lots where buyers could raise their “own vegetables and chickens as well as tropical fruits and flowers.”

William P. Woodworth operated the Oakwood Poultry Farm on lands east of 49th Street South near 16th Avenue. Subsequently, the location of his Disston City chicken-and-egg business became St. Petersburg’s Oakwood subdivision.

Boom-time expansion

Additional suburbs appeared during the early 1920s. Beginning in the summer of 1922 on lands immediately south of the Pinellas Trail between 37th and 46th Streets, many of the original lots in Fuller’s Garden Homes exceeded two acres. Industrial sites replaced most homes and gardens in Fuller’s Garden Homes after 1950.

In January 1923, Edgar Linn began selling lots in Victory Heights. He bought this acreage — between 5th Avenue South and the Pinellas Trail, from 46th to 49th Streets South — from Henry H. Victory. In 1924, Vinsetta Park became a hot spot on the other side of the Trail, between 44th and 49th Streets South.

In early 1924, the Sunny Slope neighborhood formed south of 18th Avenue South, near the former Ostrich Farm. Lots sold for as low as $800. Just south of this area, Dr. J.A. Childs had donated land for Childs Park Elementary School, which also opened in 1924.

Located between the trolley line and the new school, developers touted Sunny Slope as a subdivision “where a little means a lot.”

A century ago, ads proclaimed that the sweet grapefruit grown at Golden Glow Groves required no sugar. Soon thereafter, the trees located on Golden Glow lands between 46th and 49th Streets South, from 20th to 22nd Avenues South, became homesites.

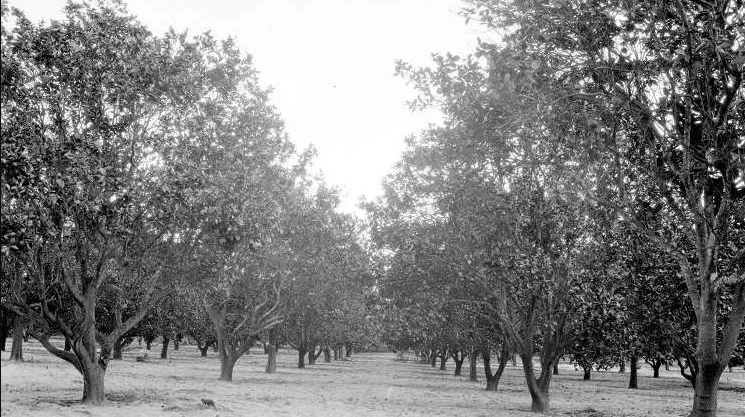

Grapefruit groves such as these grew throughout the Childs Park area a century ago. | Photo from USF Digital Collections

Gulfport developer William Roe began selling lots in his Tangerine Gardens subdivision in October 1925. Located north of 18th Avenue South, near Douglas L. Jamerson Elementary School, this became one of the last major areas marketed before the land boom came to an end.

A shared separation

Despite their unique characteristics, Childs Park’s subdivisions shared a similar demography: No Black homeowners lived in Childs Park by the 1920s.

Many white homeowners expected their leaders to maintain segregation. They implored mayors and City Council members to pass ordinances that would prohibit nearby Black residential districts. White residents occasionally formed “protective associations” to maintain the “character” of their neighborhoods.

Redlining and white flight

Neighborhoods west of 34th Street South remained all-white during the early 1950s. As Black residents began to move into areas south and west of Jordan Park and Campbell Park, some real estate brokers used scare tactics.

These agents played upon the fears of white residents. White property owners sold low, brokers handsomely profited, and neighborhoods quickly transitioned.

By the late 1960s, Thirteenth Street Heights, Cromwell Heights, and other neighborhoods north of Lake Maggiore had majority Black populations.

Fairmount Park Elementary opened in September 1957. At that time, no Black students lived near the school. The first Black teacher transferred to the school a decade later.

Black residents began to move into homes in eastern Childs Park by the 1960s. A decade later, many neighborhoods throughout Childs Park experienced a similar pattern of brief integration, followed by a relatively rapid resegregation.

Why did this happen? Hateful racial stereotypes persisted. Redlining (per the New York Times, “government maps that outlined areas where Black residents lived and were therefore deemed risky investments”) and other practices discouraged white residents from remaining in — or moving into — Childs Park’s neighborhoods.

Childs Park Elementary had a few Black students in 1967. Three years later, the proportion soared to 40 percent.

Midlife challenges

Although court-mandated busing integrated Pinellas County schools after 1971, patterns of white flight in Childs Park continued.

As white residents left the area, church members who once lived nearby now commuted for fellowship.

St. Andrews Russian Serbian Orthodox Church began to offer services at 4668 15th Avenue South in the early 1950s. After the flock moved to a new building on 54th Avenue North, this structure became the home of Ebenezer New Testament Church of God.

Services for the Childs Park United Methodist Church began under large oak trees near the intersection of 18th Avenue and 40th Street South in 1920. After Dr. J.A. Childs donated land, the congregation built a house of worship. Membership soared to nearly 700 by the 1960s but declined to under 50 by the new millennium.

Members of Rock of Jesus Missionary Baptist Church now worship at the former Childs Park United Methodist Church, built in 1925.

Although Childs Park United Methodist welcomed members of all races by the 1960s, the church held its last service in June 2002. Presently, its 1925 masonry and brickstone structure serves as the home of the Rock of Jesus Missionary Baptist Church.

Childs Park Elementary became a fundamental school in the fall of 1978. Lacking air conditioning, the once-ornate campus suffered from mold, mildew, and cracked plaster. Despite the district spending nearly $600,000 to maintain the building between 1989 and 1994, the school closed in June 1995. Subsequently, a wrecking ball demolished the school.

No Childs left behind

Efforts to improve Childs Park’s long-neglected neighborhood institutions have occurred during the last quarter-century. A major school renovation plan announced in August 1999 led to the reconstruction of Fairmount Park Elementary. Classes at Jamerson Elementary began in 2002.

The former Childs Park Elementary campus expanded from 5.5 acres to nearly 20 after demolishing more than 50 homes. Presently, this is the home of Thurgood Marshall Middle School. Also, a newly rebuilt Gulfport Elementary School reopened 20 years ago that serves many Childs Park families.

Built as the Sunshine Masonic Lodge in 1924, this structure now serves as the home of the Christ Centered Church of God in Christ.

Since its construction in December 1977, the Childs Park Community Center enjoyed enhanced programs. Later, a pool opened in July 2002. Since then, the neighborhood has obtained a public library branch.

Later in life, Childs developed the Big Bayou and Bayou Bonita areas. A longtime user of the trolley system, he appeared in a St. Petersburg Times photograph, standing next to a streetcar during its last Big Bayou run in January 1948. L.D. Childs passed away in June 1952 at the age of 86.

This article was originally published in The Gabber on Oct. 24, 2023.