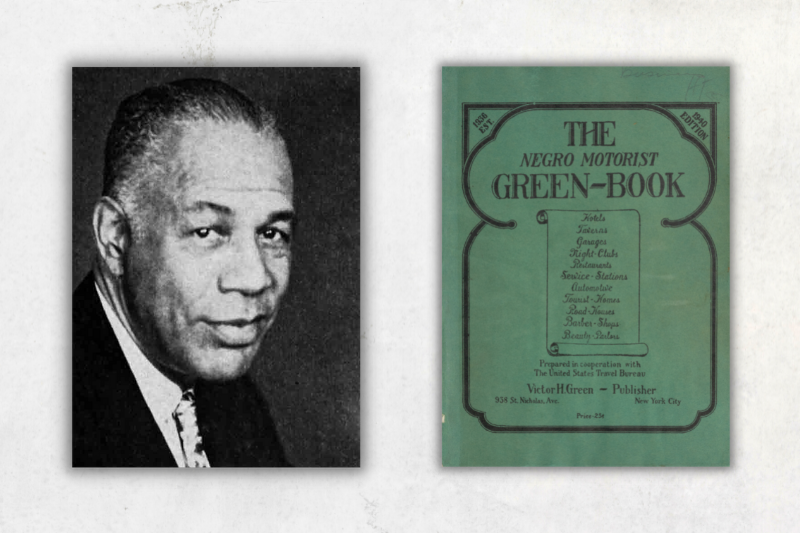

The Green Book was originated and published by African-American New York City mailman Victor Hugo Green from 1936 to 1966 during the era of Jim Crow laws. Seen here is the cover of a 1940 edition.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — For 30 years, “The Negro Motorist Green Book” (also known as “The Negro Travelers’ Green Book, or simply the “Green Book”) served as an invaluable guidewhen segregation was the policy in many restaurants, stores, hotels and gas stations around the country. Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, FL, Inc., discussed the historical importance of the guidebook founded by Victor Hugo Green for African Americans taking road trips.

When it first appeared in 1936, it covered the New York area, where Green lived and worked for the United States Postal Service. Eventually, he expanded it to include much of North America, Reese said, even listing locations outside the United States in later editions. It was published from 1936-1966.

“It actually became the bible of Black travel,” Reese explained, during a time when discriminatory Jim Crow laws prevented Blacks from stopping at certain places or even performing necessary functions of road travel.

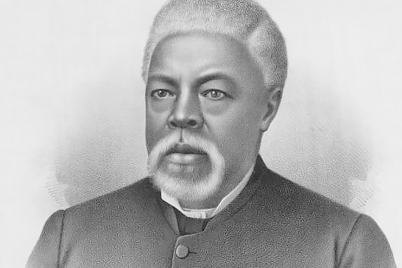

Many hotels and restaurants excluded African Americans, such as this one in Ohio, seen in 1938.

“We’re talking about things as simple as not being able to stop at a gas station to put gas in your car; not being able to stop and get something to eat on the road; hence, we had what we used to call ‘shoebox lunches’ because you pack up your lunches and carry them in the car. Because nine times out of 10, you would not be able to find a place to stop to eat.”

She recalled a road trip her family took to North Carolina when she was a child, where her father had to pull over by the side of the road when young Reese or one of her siblings had to use a restroom — simply because they had not passed a facility that Blacks could use. In those days, African-American travelers — Reese’s family included — tried to complete all their driving in the daylight because it was not safe for them to be on the road after dark, especially in the South.

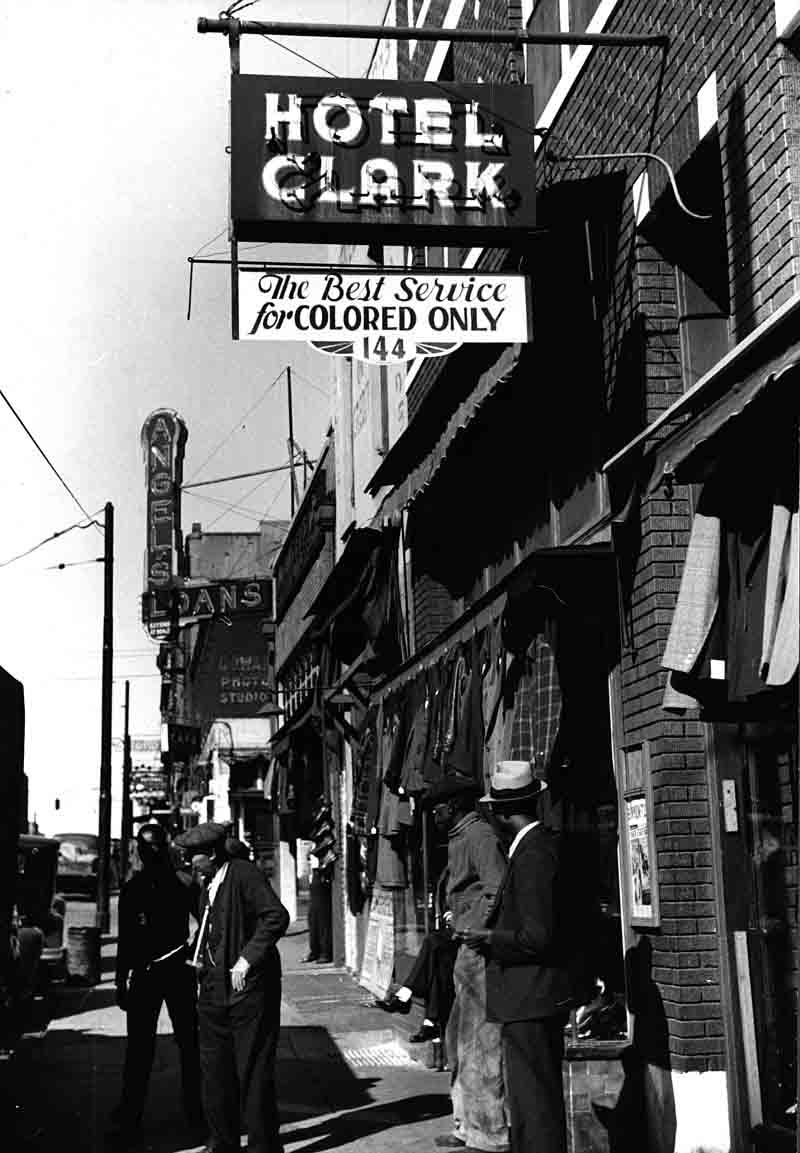

The “Colored only” Hotel Clark in Memphis, circa 1939

“It was published when there was so much discrimination against African Americans when we faced racial prejudice, price gouging. Prices would be doubled for African Americans!” Reese stated.

In addition to unfair pricing and lodgings that outright refused Black travelers, physical violence was always a threat. She recalled one day when she was very young, and her family was driving on U.S. 19 near Oldsmar. Out the window, young Reese spotted a gathering of people with white robes, and they were burning a cross.

She didn’t know what any of it meant. Her father instructed her and her siblings to put their heads down and not look at the strange spectacle. Only when she was much older did he explain what they had encountered.

“The information in the “Green Book” provided ways for Black people to be safe and travel together along the roads of the United States,” she said. “It was an invaluable source.”

Reese noted that the “Green Book” era was a time of segregation and racial terror lynching throughout the country, including here in St. Pete. It encompassed an incendiary time of protests for racial equality here in the city, including demonstrations against redlining, strikes for the rights of sanitation workers, and a lawsuit for the rights of Black police officers to patrol the entire city.

Stores such as Kress and McCrory’s, fixtures of downtown St. Pete, wouldn’t serve Black diners, Reese remembered. And although African Americans could buy clothes and shoes in shops on Central Avenue, they were not permitted to try them on. Likewise, the famous Green Benches of St. Pete were social gathering spots in the city for years — some ladies, all dressed to the nines, even met future spouses there – yet Black people were not allowed to sit on them.

As a result, African Americans had their own vibrant business corridor on 22nd Street South, which was dotted with all manner of shops, diners, and social clubs. When Black residents purchased goods in Black-owned stores and patronized Black-owned restaurants, they were treated respectfully. Even when superstars as famous as Louis Armstrong – who once dined with the Royal Family — came to town, he had to play the Manhattan Casino — as a part of the Chitlin’ Circuit — since he could not play white-only venues.

“It was a time of terror; it was a time of deprivation; it was a time of separate but not equal,” she said. “It was a time of white-only restrooms and white-only swimming pools and white and colored drinking fountains, and white-only waiting rooms. It was the era of Jim Crow.”

Consequently, many Black travelers visiting Tampa Bay and elsewhere made sure they stowed a copy of the “Green Book” not only because it was a handy guide but a necessity.

“This was Victor Hugo Green’s way of making travel in this country safer for Black people,” Reese said, “so that we could travel with dignity and respect and be safe in doing so.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com