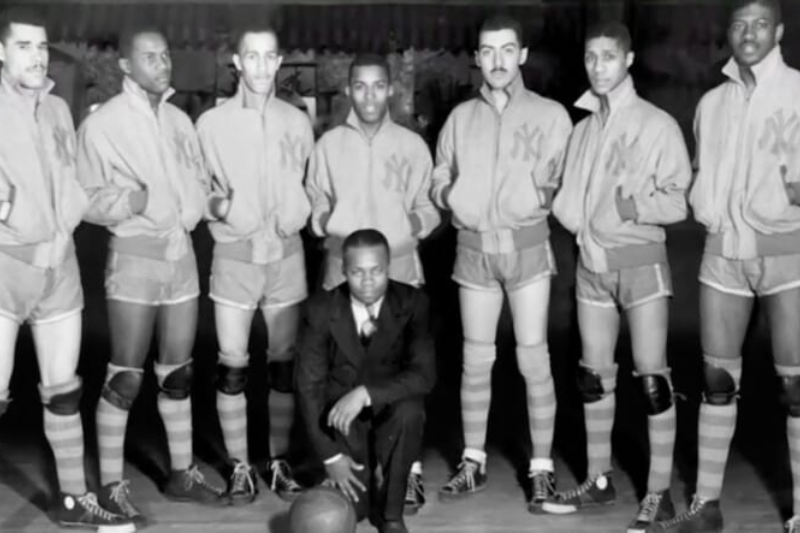

The New York Renaissance, also known as the Harlem Renaissance or the Rens, was the first Black-owned, all-black, fully-professional basketball team established in Oct. 1923 by Robert “Bob” Douglas. The New York Renaissance (Screenshot/YouTube, ‘On the Shoulders of Giants’)

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

In the 1920s, Harlem, a neighborhood in New York City, was in the midst of an awakening in thought, art, music, expression — and sports. At the center of what historians came to dub the “Harlem Renaissance,” such famous names loomed large, including poet Langston Hughes, musician and writer James Weldon Johnson, author Zora Neale Hurston and bandleader Duke Ellington, to name a few among the many writers, sculptors, painters, and philosophers that helped shape the movement.

Yet a basketball team made its own impression in this jazzy, free-spirited era that we often overlook: the appropriately named Harlem Renaissance or sometimes called the New York Renaissance, or Rens, as they were locally known.

William Roche, who came to Harlem from the island of Montserrat, built the Harlem Renaissance Casino in 1922. This two-story center ran feature films in its first-floor showroom, while on the second floor was a spacious ballroom available for banquets, concerts and basketball games.

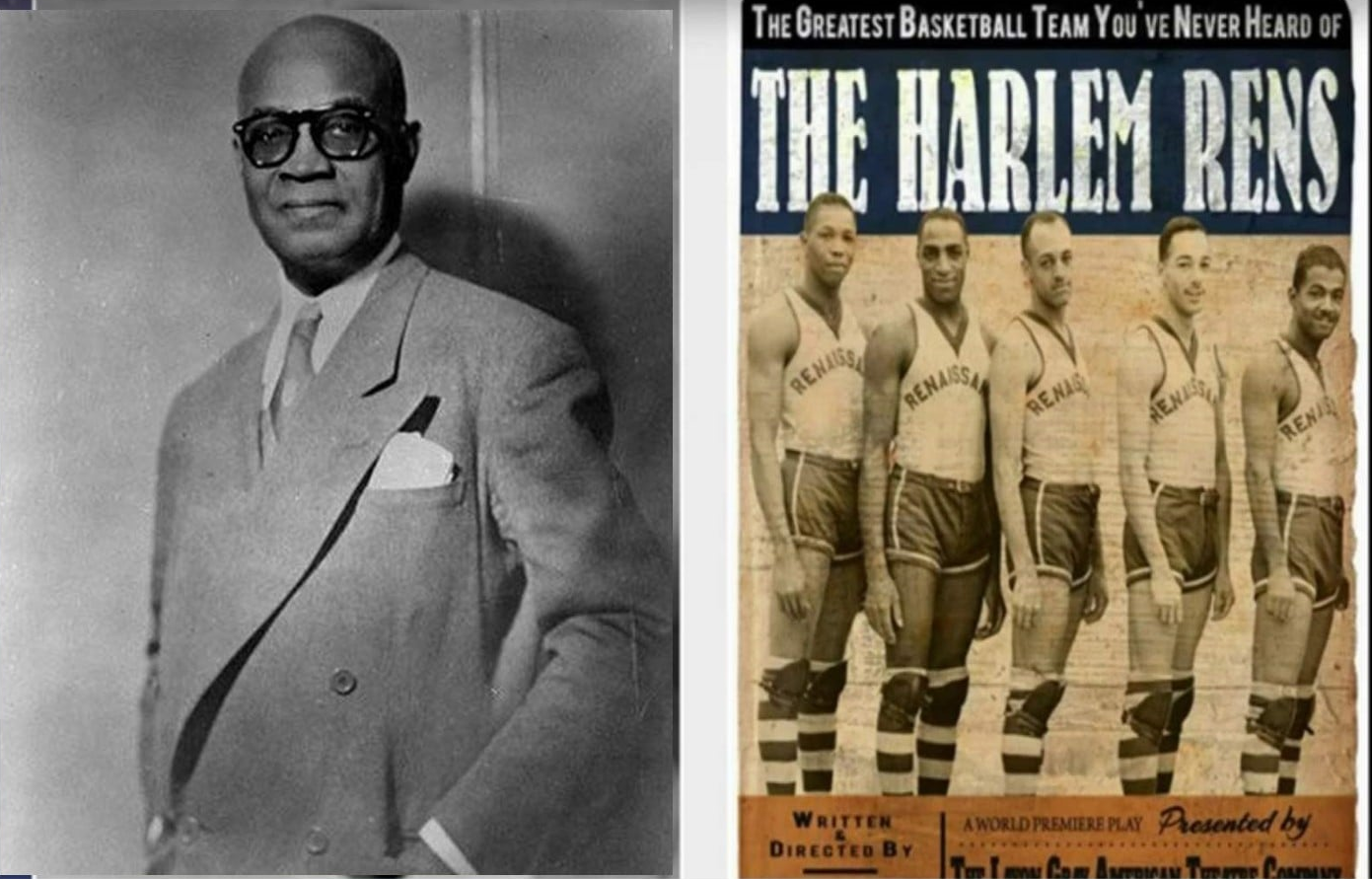

In fact, fellow Caribbean immigrant Robert L. Douglas urged Roche to offer basketball at the center for entertainment. Often considered the Godfather of Black Basketball, Douglas was a crucial figure in professional basketball’s future growth.

Robert L. Douglas founded the New York Renaissance basketball team, the first fully all-black professional black-owned basketball team. © Facebook/Concerned Citizens of Whitesboro, Inc.

According to Nelson George’s 1992 “Elevating the Game,” innovations of Douglas’s would include “monthly contracts with his players, a custom-designed team bus, and tours in the South, which he began before the region was considered a significant market for the game.”

One century ago this year, Douglas convinced Roche to feature basketball games in the ballroom, and as an added incentive, the team would be called the Harlem Renaissance. Roche agreed, and the team debuted in November 1923, beating the Chicago Collegians by 28-22. George wrote: “Under a chandelier beneath which the big bands played, the Rens took set shots and tried not to scuff up the floor too much.”

The first Black-owned, all-Black professional team, the original Rens were Leon Monde, Hy Montre, Zack Anderson, Clarence “Fats” Jenkins and Frank Forbes. Under their coach and road manager Eric Illidge, the Rens managed to win an incredible 2,318 while losing only 381 games in their history.

They employed a “team first” mentality and shunned individual hot dogging or “hogging” the ball — things many players would be guilty of in ensuing decades. For one thing, the actual balls made in the ’20s had fat laces, making fancy dribbling difficult.

Game nights back then were not merely athletic contests but social events, as gussied-up young men and women would come to cheer for the Rens and then dance the night away to lively big band music.

The game of basketball itself, only invented in the 1890s, underwent significant changes during the rise of the Rens. The center jump after every basket was done away with, while the ball itself became smaller (as did its laces), which made dribbling much easier

“These changes made speed and leaping ability more important—factors that favored Douglas’s all-Black squad,” George wrote.

In their early years, the Rens only played in New York City but expanded to compete in the Northeast, Midwest and South. As integrated competition was permitted in pro basketball, the Rens developed rivalries with white teams such as the Original Celtics of New York, run by Joe Lapchick, who held a healthy respect for the Rens players.

While playing a local team in Louisville, Ky., one day in the 1920s, the Rens were surprised to look up and see members of the Original Celtics taking in the game. George noted in his book what Douglas remarked about that day:

“Joe Lapchick, who knew our center Tarzan Cooper, ran out on the court and embraced Cooper because he was so glad to see him. There was a silence on the court. This was Jim Crow country, and the races were strictly separated. The Celtics were put out of their hotel and a riot was narrowly averted.”

It was in the 1930s that the Rens galvanized their reputation for featuring some of the best ballers, well, anywhere. Center Wee Willie Smith, appropriately, formed the centerpiece of a fearsome squad. With electric players James Pappy Ricks, Eyre Saitch, Bill Yancey, Johnny Holt and Charles “Tarzan” Cooper also on board, from 1932-36, the Rens put up an eye-popping record of 473-49.

As feared as the team was on the hardwood, their manager was just as tough. When the Rens were on the road, “Illidge carried a tabulator to count the gate and a gun to make sure he took home what he counted,” George wrote.

Douglas himself insisted that the Rens would not take the court until Illidge had the payment in his hand. Douglas also sprung for a customized bus, letting his team travel in style in a vehicle with reclining seats and the capability of carrying food.

A luxury for any team back then, it also helped them avoid certain indignities — something a team of Black players traveling around the country would no doubt come across in the South.

In the 1930s, Douglas felt his team was the best in the nation. When a professional tournament was finally organized in Chicago, it was his chance to prove it. The mighty Rens scythed their way through a field of eight teams, culminating in a “world champion” title on March 28, 1939. In the hotly contested final showdown — with no shortage of physical contact between the teams — the Rens beat the all-white Oshkosh All-Stars 34-25.

In the New York Evening Telegram, writer Joe E. Williams noted, “They are the champions of professional basketball in the whole world. It is time we dropped the ‘colored’ champions title.”

The Rens and Douglas were trailblazers in their time, as the team demanded respect from their opponents and did not resort to clowning and “entertaining” the white populace as many Black barnstorming teams did before them. Douglas earned his induction to the Basketball Hall of Fame in 1972 as the first African-American honoree.

The Rens played from 1923-48 — compiling a record of 2,588-529 in that stretch — until their move to Dayton, Ohio, for the 1948-49 season. After a single season as the Dayton Rens, the team that had dazzled crowds nationwide finally disbanded.