The identity of art

Still thinking practically, Norwood decided to pursue a degree in fine arts at the University of South Florida because she’d always believed the best graphic designers were the ones with an art background. This decision to go back to school changed her way of looking at the world.

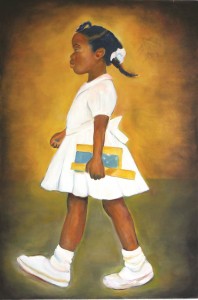

Still thinking practically, Norwood decided to pursue a degree in fine arts at the University of South Florida because she’d always believed the best graphic designers were the ones with an art background. This decision to go back to school changed her way of looking at the world. Putting herself in her work is something that comes intuitively to Norwood, especially in her paintings. This is quite apparent in such works as “Pearl,” Norwood’s take on the famous 1665 Johannes Vermeer painting “Girl with a Pearl Earring.” Norwood depicts an African-American girl in the iconic pose, and there is more than a passing resemblance between the subject of “Pearl” and Norwood’s own visage.

Putting herself in her work is something that comes intuitively to Norwood, especially in her paintings. This is quite apparent in such works as “Pearl,” Norwood’s take on the famous 1665 Johannes Vermeer painting “Girl with a Pearl Earring.” Norwood depicts an African-American girl in the iconic pose, and there is more than a passing resemblance between the subject of “Pearl” and Norwood’s own visage.