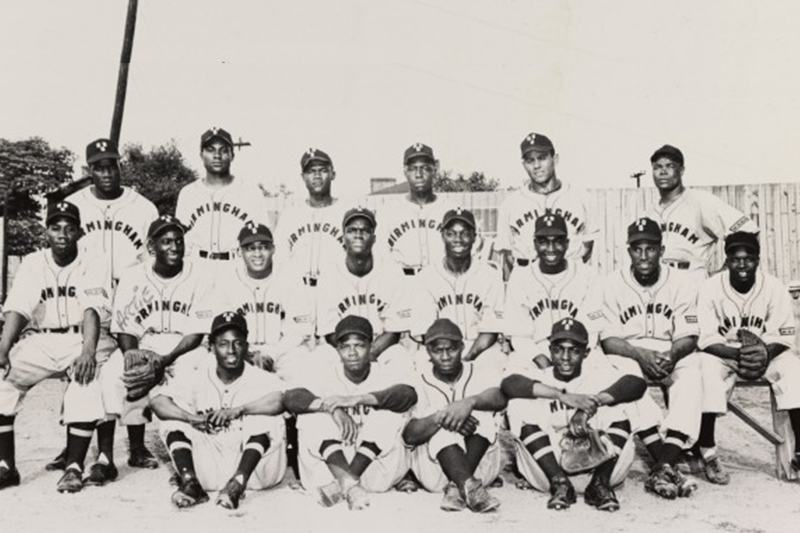

The 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, Courtesy of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Inc.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

For breath-taking World Series moments, the last Negro League World Series ranks up there among the very best.

In Game 1 of the 1954 Series between the New York Giants and the Cleveland Indians, the score was tied 2-2 in the top of the eighth inning. With runners on first and second and no one out, the Indians were threatening to break the game open as slugger Vic Wertz stepped to the plate.

On the fourth pitch, the dangerous Wertz swung mightily and launched the ball deep into the cavernous centerfield of the Polo Grounds in New York — it would travel about 420 feet in all. The runners on base bolted right away, certain no mortal fielder could catch up to a ball hit that far.

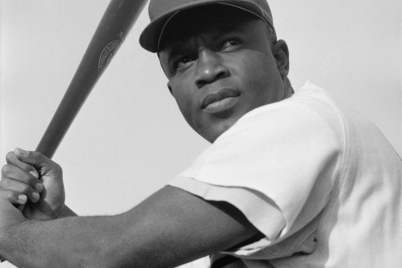

But a fleet-footed centerfielder named Willie Mays turned and ran like a sprinter at the crack of the bat, making a manic dash toward the fence where — with his back still to the infield — stuck out his glove and hauled in his prize, short of the warning track.

After the jaw-dropping, over-the-shoulder catch, he spun immediately and heaved the ball back toward the infield, forcing the runners — who had seen no need to tag up on a ball smacked so far — to go scampering back to their bases. The magnificent grab preserved the tie, and after the Indians failed to score, the Giants ultimately won the game in the tenth inning. It came to be known simply as “The Catch” and lives on as one of the truly great World Series moments.

But far fewer people got to witness an arguably more impressive Series performance by the incredible Mays when he almost single-handedly beat the opposing team with his legs, glove, arm and bat.

It was 1948, and the Birmingham Black Barons were set to face the Homestead Grays in what would be the last Negro League World Series. With many financially struggling ball clubs folding all around and Jackie Robinson breaking the color line in the Majors the year before, the death toll was sounding for these longstanding leagues in which so many black ballplayers excelled and entertained.

And one of the biggest rising stars of the Negro American League was Mays, then a 17-year-old phenom.

Hailing from Westfield, Ala., young Mays was still in high school when he began playing for the Black Barons. His father, “Cat” Mays was a talented and speedy outfielder in his day, but it was apparent to all that son Willie had more talent and certainly more speed from the moment he stepped onto the field. What’s more, he played the game with the effortless, youthful exuberance of a kid on the sandlot with his friends, having a ball.

The Negro League had a lingo all its own, and in this colorful slang, black ballplayers all agreed that Mays possessed an “awful” arm — that is an awfully good one. Even as a kid, he could run down balls that could’ve been blasted from canons, snagging them out of the air with his trusty glove. In turn, he could send a ball screaming back to the infield with a speed of an express train, nearly burning holes in his infielder’s mitts as they caught his powerful and dead-on throws.

Though he batted respectively, he had trouble finding a comfortable hitting groove early in his career. This was really the only weakness his opponents saw in this kid, and his opponents in the 1948 World Series were the mighty Homestead Grays of Washington, D.C. — a team that had beaten the Black Barons in the 1943 and 1944 World Series and were looking to whip them again.

After outlasting the fearsome Kansas City Monarchs in a grueling series for the Negro American League crown, the Black Barons quickly found themselves in the hole after the first two games against the Grays, led by future Hall of Fame first baseman Buck Leonard.

In Game 1, the Barons were down 3-1 in the late innings with Mays on third base and teammate Pepper Bassett on first. Player-manager Piper Davis then stepped up and promptly whacked a triple to right field.

Mays scored easily, but Bassett, a big man huffing and puffing his way toward the plate, saw the Grays’ catcher Eudie Napier ahead of him, waiting for the throw from right field. After a dusty collision at the plate, umpire Frank Duncan of Kansas City called Bassett out. The Black Barons dropped Game 3-2.

Mays and his teammates were happy to be in Birmingham for Game 2, in their own Rickwood Field. Games at Rickwood were always an event, as the hand-clapping, foot-stomping fans infused the park with all the infectious buzz and passion of an enormous outdoor church revival. Up by a score of 2-0, Barons’ veteran starter had pitched an efficient two-hitter into the sixth inning when he promptly self-destructed.

After giving up a couple of singles, Powell walked the ever-dangerous Buck Leonard. The Grays’ Wilmer Fields smacked what looked like an easy inning-ending double-play ball to Davis at second, but misfortune intervened for the Black Barons. Davis’ toss to infielder Artie Wilson lodged in Wilson’s glove and a run scored, cutting the lead to 2-1. Napier then slapped a single to tie the game.

Running out of steam, Powell served up a pitch that Willie Pope like so much that he launched it over the wall for a three-run dinger, putting the Grays up 5-2 and effectively sucking all the air out of Rickwood Field. But there was still some fight left in the Black Barons, who closed the gap to 5-3 when pinch hitter Herman Bell hit an RBI double.

Manager Davis pulled the slow Bell from second base and inserted speedier pinch-runner Jehosie Heard. Wilson was up next, but when he went down swinging, chasing his big weakness — the high fastball — the Barons were down to their last out.

Third baseman John Britton stepped up to the plate, and if he could find a way to somehow get on, Mays was ready on deck, waiting for his big chance to set off his own brand of fireworks in the Birmingham sky. Though the teenaged Mays was still trying to establish himself as a feared hitter, the youngster certainly picked his moments to impress.

In his book about the 1948 Black Barons titled “Willie’s Boys,” author John Klima wrote: “Nobody considered Willie a kid when he batted in a man’s situation.”

Sadly for the Barons and the Rickwood faithful, he never got the chance. Britton’s ground ball out ended the contest, giving the Grays a commanding 2-0 lead in the Series. The kid would have to wait for his chance.

The Black Barons wanted more than anything to win a World Series game against the dreaded Grays in Birmingham. Referring to Mays’ performance in Game 3, Klima wrote: “For the first time in a meaningful game, he put all of his fantastic skills together at once, proving that he could beat you with his speed, his defense, his throwing, and when it mattered most his hitting.”

Mays wanted to win so badly he was willing to put his entire team upon his sturdy shoulders and carry them to victory himself if need be. In Game 3, he would show the baseball world that he was indeed a giant among men.

Barons’ starter Alonzo Perry and Grays’ hurler Ted Alexander were locked in a scoreless duel through three innings when Homestead power hitter Bob Thurman — who boasted as a young man he “could hit a ball nine miles” — turned on a pitch and sent it flying toward center. Thurman gave it such a ride that he figured he had a double for sure, but Mays had already started running.

The teenaged speedster was making up impossible ground on the soaring ball as pitcher Perry looked on, and Thurman came trotting up to second base where Artie Wilson was waiting to deliver the news to the hapless hitter: the centerfielder caught your fly ball. You’re out.

The Rickwood crowd feverishly praised and applauded the young wizard of the outfield. By then, many had been going to the ballpark just to see Mays make such impossible plays. In the fifth, Perry helped his own cause by driving in a run with a double, putting the Black Barons up 1-0.

In the next inning, Buck Leonard was on first base. Leonard, who had seen Mays play a couple games but never witnessed his superhuman ability to throw a baseball, took off as soon as the following hitter singled to center.

Thinking it fairly routine that he could reach third base after getting a good jump, Leonard barreled toward third when all of a sudden, an object came zipping through the air like an angry arrow and thwacked right into third baseman Britton’s waiting glove.

In horse racing terms, the incredulous Leonard was out by two lengths. The veteran later admitted that he was not only flabbergasted that a kid could make such a strong throw but such an accurate one, to boot.

The Black Barons increased their lead to 3-1 thanks to a wild pitch, but the Grays battled back in the eighth when Thurman smashed a two-run double to tie the game 3-3. In the last at-bat for the home team, Bill Greason led off with a line-drive single.

After Wilson flied out, Britton then walked. With the winning run on second base, Mays made his way to the plate. He had astounded the Grays with his speed and his arm, and now it was time for his big stick to do the talking. With the hopes of his team riding on him, Mays turned on Alexander’s pitch so fast that he sent it whistling back at the pitcher, through his legs and into the outfield. Mays started running, and so did Greason, who turned on the jets and loped his way around the bases.

Luis Marquez, the Grays’ centerfielder with an average arm, fielded the ball and tossed it back in but Greason, who never stopped running and scored easily without a play. Mays’s game-winning hit threw the ballpark crowd into hysterics, and the hometown boys finally defeated the hated Homestead Grays.

Mays’ manager and mentor, Piper Davis, hugged Mays at the end of the game — something the stoic disciplinarian rarely ever did. As Klima wrote, left fielder Jimmy Zapp said of teammate Mays after the game, “Here we thought we was the ones makin’ him better, but it was the other way around.”

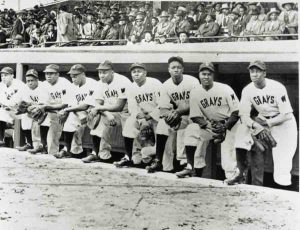

The Washington Homestead Grays circa 1946.

Courtesy of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum Inc.

It was clear on that day fall day in Birmingham that the players and fans had witnessed something special. Major League scouts also witnessed the Mays magic as well.

The Grays would have their complete revenge for that loss when they obliterated the Barons 14-1 in Game 4 and went on to beat a dispirited Barons team in Game 5 by a score of 10-6, winning the Series. It was the final Negro League World Series for good, as the Negro National League folded at the end of 1948.

A few of the surviving teams soldiered on in the newly-formed Negro American League eastern Division, but the writing was on the ballpark walls. The Negro Leagues were on their way out. The Homestead Grays, champs of 1948, didn’t exist after the 1950 season.

Some of the players found their way to the big time of “white folks’ ball,” as black ballplayers called it. There was no shortage of interest in the multi-talented Mays, as the Boston Braves, Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants all scouted him. It was the Giants that won the day, however, as they signed Mays to their minor league affiliate.

In 1951, Mays debuted for the Giants and played every one of his 22 seasons with them in New York and then San Francisco, after their move out west in 1958. Over two decades later, the mark he made on the game could never be diminished.

The “Say Hey Kid” finished his playing days in 1973 with a career batting average of over .300, banging out over 3,200 hits and blasting 660 home runs. He was a 24-time All-Star and a World Series champ in 1954 when his Giants swept the Indians — the Series where Mays made his historic catch.

Although that miraculous grab has been celebrated throughout the decades, players and fans who had seen Mays play as a teen probably wouldn’t have even called it his best catch. After all, they had witnessed Willie the Wizard make such stupendous plays before, on the rustic fields of the Negro Leagues.

Furthermore, many black ballplayers felt that the caliber of their Negro League baseball was every bit as strong as white folks’ ball. Talented squads such as the Homestead Grays and Birmingham Black Barons could more than hold their own against the New York Yankees or St. Louis Cardinals, they argued.

And with no shortage of legends such as speed demon Cool Papa Bell, home run king Josh Gibson and fireball pitcher Satchel Paige — who would wind up in the Majors himself — few could argue the quality of their game.

Mays will be remembered for many things –The Catch among them –but he should always be acknowledged as a man who helped bridge the gap between men playing in cozy, segregated Negro League parks to black and white ballplayers sharing the field in big-time Major League stadiums.

Source: “Willie’s Boys: the 1948 Birmingham Black Barons, the Last Negro League World Series, and the Making of a Baseball Legend,” by John Klima (Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2009).