Shackling a woman by the ankles, wrists, and waist during pregnancy and delivery is medically hazardous, emotionally traumatizing, and unnecessary for security reasons.

BY JESSIKA WARD, Dream Defenders

Studies have shown that incarcerated Black women are at higher risk of premature births. These results are said to be because of economic and social impacts stemming from mass incarceration and population health and health inequities that exist for Black babies whether their mother is incarcerated or not, including the persistence of racial disparities in preterm birth and low birth weight for all Black babies.

It is known that often white medical personnel believe Black people don’t feel pain in the same way white people do. This same stigma is also seen in prisons and jails. Correction officers and doctors often don’t take the pain of incarcerated Black women seriously.

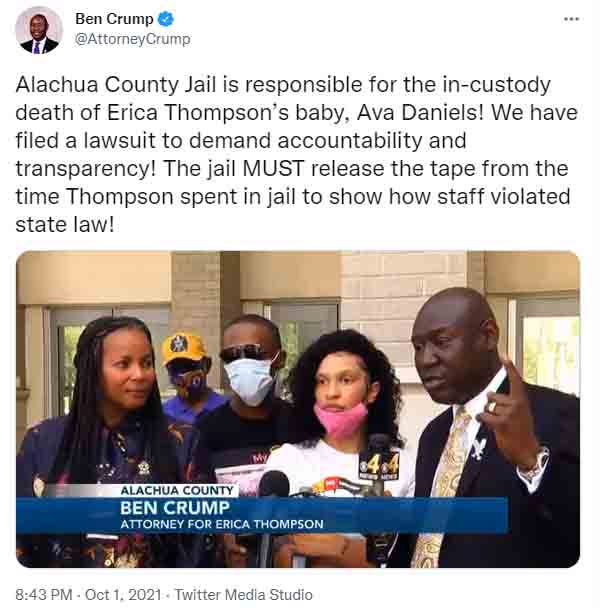

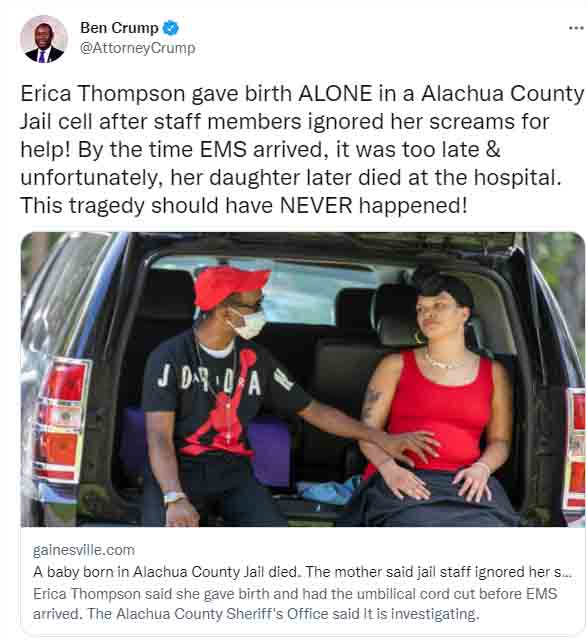

In Alachua County, a Black woman named Erica Thompson was seven months pregnant when she was arrested for violating her probation for a traffic citation. According to Thompson, she told jail staff that she was experiencing contractions but was not given the proper attention or care.

The baby, named Ava, later died after Thompson prematurely gave birth inside the Alachua County jail. Now, Attorney Ben Crump will represent Thompson as she sues the jail for the wrongful death of her infant.

Being pregnant and giving birth are amongst the most memorable experiences in a woman’s life. The postpartum experience should be one of bonding between a mother and her child. However, this experience is much different for women who are in jail and prisons.

Shackled until the moment they give birth with only law enforcement and a doctor present, these women are only given 24 to 48 hours with their newborn until their baby is taken away. Giving birth while incarcerated is one of the most inhumane experiences a person will go through.

The postpartum experience for incarcerated women is not one of mother-to-child bonding; it is instead a period of lactating with no baby to breastfeed and heavy bleeding without access to a laundry machine or proper menstrual products.

The Prison Policy Initiative predicted that 55,000 women in the United States would be arrested while pregnant this year. According to their study, in the United States, there are more women in jails than in prison. People in jail are incarcerated for under a year and held for minor crimes, whereas prison describes a place for convicted criminals of serious crimes.

However, when studies are conducted, and numbers are calculated to track the number of births behind bars, the numbers are combined. Kimberly Haven, a formerly incarcerated individual and the executive director of Reproductive Justice Inside, said that her organization works with prisons and jails to conduct accurate studies.

“It’s hard to help change the system when we don’t have accurate numbers,” said Haven. “We need the jails and prisons to share accurate information with us so that we know how to help. Some [jails and prisons] try to do the right thing, but there are still some that don’t.”

In a single year, women in prison and jail had 753 live births, 46 miscarriages, four stillbirths, and 11 abortions. Of the 753 live births, there were three newborn deaths and no maternal deaths, and nearly a third of the live births were cesarean deliveries.

As laws are being passed to ban abortions and place those who have experienced miscarriages or stillbirths under suspicion for criminal acts, incarcerated women are dying and losing their babies inside prison and jail walls. So are the health rights of women being violated while pregnant and in prison?’

“Many women give birth in prisons and jails every year, but many more give birth in hospitals because most prison medical units aren’t equipped to handle deliveries,” said Wanda Bertram, communications strategist of the Prison Policy Initiative.

Though incarcerated women may give birth inside of a hospital, these women are usually shackled. The shackling of pregnant prisoners and over-incarceration of pregnant women are all major concerns, but so are the healthcare needs of expectant mothers, healing from childbirth, and lactating.

Shackling a woman by the ankles, wrists, and waist during pregnancy and delivery is said to be medically hazardous, emotionally traumatizing, and unnecessary for security reasons. According to the “AMA Journal of Ethics,” pregnant women who are shackled are at increased risk of falling and sustaining an injury to themselves and their fetuses.

The “AMA Journal of Ethics” reports that most correctional facilities do not have on-site obstetric care. Because of this, pregnant women are typically transported to community-based providers for prenatal care, and women in labor are transferred to medical facilities for delivery.

Organizations are working daily to help incarcerated pregnant women gain access to prenatal and postpartum medical care. Whether an incarcerated woman decides to carry her pregnancy to term or have an abortion, she has a constitutionally protected right to obtain appropriate medical care.

“This neglect of pregnant women is likely often illegal because people in prison have a constitutional right to be afforded proper medical care,” explained Bertram, noting the Supreme Court decision in a 1976 case called Estelle v Gamble.”

“Currently, we know that individuals in the care, custody, and control of the state do not know

what to expect during their pregnancies, nor do they know their rights to care,” said Haven. “Clear policies are needed to inform standards of care for pregnant people.”

With the medical and legal expertise of Reproductive Justice Inside and informed by the voices of the directly impacted, they have developed the nation’s first comprehensive Model Pregnancy Policy Manual that covers specific subjects such as pregnancy testing, prenatal care, high-risk pregnancy care, miscarriage management, abortion care access, labor and delivery, postpartum care, counseling, and social services.

Once a woman gives birth, she bleeds and lactates. This natural progression of life is a complication while inside a jail or prison. Institutions don’t always provide mothers in the postpartum phase unrestricted access to hygiene products commonly used by mothers after giving birth—underwear, sitz baths, chux pads, and other items.

Institutions also don’t have appropriate waste disposal receptacles for these items. Some facilities create systems to pump and store breast milk that can later be delivered to the infant, but most don’t allow this.

“Let’s also look at breast milk; oftentimes, pumping is not afforded to the individual. Given everything we know about how important breast milk is for infants, the fact that this is not practice is unacceptable,” said Haven. “Individuals should be given the opportunity, supplies, and education to pump their breast milk on their body’s schedule and to make it available to the caregiver of their infant.”

Reproductive Justice Inside has launched a new initiative that will make it easy for institutions and individuals to pump, providing dedicated refrigerators to institutions. Through litigation and advocacy, Reproductive Justice Inside works to secure prenatal and postpartum healthcare rights in prisons and jails throughout the country, attempting to end the barbaric practice of women giving birth while shackled and to protect the health of incarcerated women and their babies.

“No pregnant woman from the date of a positive pregnancy test through the postpartum period should ever be shackled. Right after she delivers a baby, you shackle her leg to the bed! It’s against the law,” said Haven. “If we don’t make these systems report out, then we can’t stop it. Some officers follow the law and try to do the right thing, but [the shackling] still happens. We need to hold these institutions accountable because we’ve seen too many times the damage [shackling] does.”

Haven said one way to end this is not to arrest pregnant women or send them to jail or prison and instead put women on house arrest or GPS monitoring.

“Let’s make maternal health and healthy birth outcomes the priority,” stated Haven. There are other ways of doing this. I do not believe putting a pregnant person or a post-pregnant person — someone who has just given birth — into an incarceration system, especially not when we know what we know about COVID-19.”

Jessika Ward is a journalist and the press secretary for the Dream Defenders, a youth-led organization that organizes Black and Brown youth to build power in Florida communities to advance a new vision the Dream Defenders have for the state.

Jessika Ward is a journalist and the press secretary for the Dream Defenders, a youth-led organization that organizes Black and Brown youth to build power in Florida communities to advance a new vision the Dream Defenders have for the state.