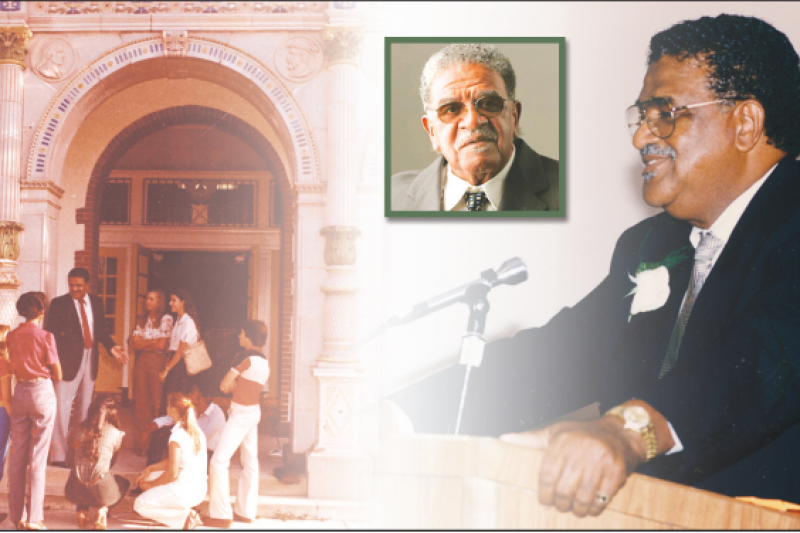

Vyrle Davis had an affection for his students that earned him widespread respect.

BY JON WILSON | Columnist

ST. PETERSBURG — A legendary educator for more than three decades in Pinellas County schools, Vyrle Davis, died Friday, Feb. 1, at age 76. His passing has generated a week of tributes and fond recollections of a teacher – and later a principal and an administrator – who lived for his students.

“Vyrle was certainly one of the greatest mentors I’ve ever had, not only from my junior high days but as an adult,” said Urban League President and CEO Watson Haynes.

“He had a program for the brightest scholars, then he turns around and decides to address the issue of academics of all African-American students with COQUEBS (Concerned Organizations for Quality Education for Black Students). Then, he decided to include all students. Vyrle was compassionate with students and children and was not afraid to say what he believed on behalf of them.”

A Tampa native, Davis went to Florida A&M University. His first teaching job in Pinellas County was at Sixteenth Street Junior High, now John Hopkins Middle School. The year was 1960, the same year he married Mozell Reese.

It was a fortuitous alliance for many reasons – one of which was the new Mrs. Davis’ talent for making a good lunch. Back in that day, teachers were expected to raise money to help supply their students with basic materials such as pencils and writing tablets. Davis raised his share by selling her chicken sandwiches.

Davis soon went up the professional ladder. He became assistant principal at Gibbs High School and, in 1973, became principal at St. Petersburg High School, an all-white school steeped in tradition. Moreover, the county’s school desegregation policy had been in effect just two years, and sometimes the atmosphere turned tense on campuses. Davis was up to the task. St. Petersburg experienced much less trouble than other high schools around the city.

A story Davis sometimes told probably suggests why.

Gibbs was playing a football game against Dixie Hollins, which emphasized its Rebel mascot, and liked to play the song “Dixie.” The school had no plans to tone down the music, which many players and fans found offensive. Gibbs soon scored a touchdown – and what did the Gladiators’ band do? They played “Dixie.”

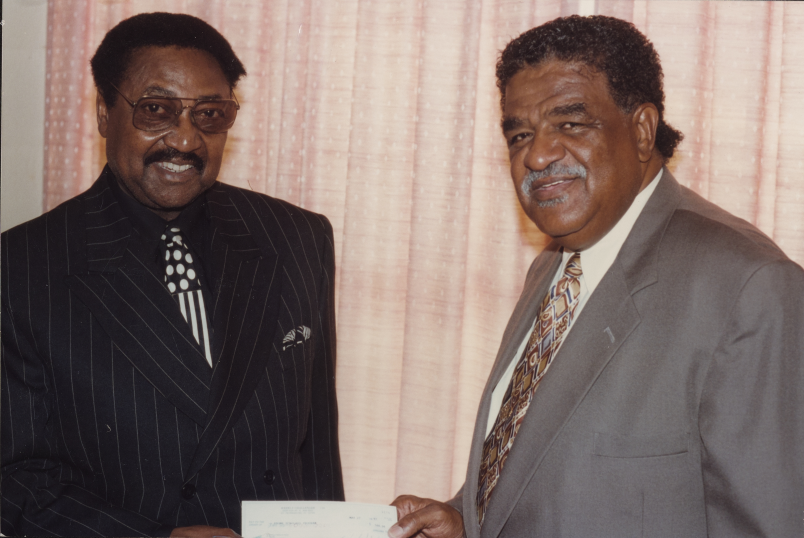

Cleveland Johnson, Jr., owner of The Weekly Challenger, is seen here giving Vyrle Davis a check for the Ebony Scholars fund.

The Gibbs students loved the turnaround. “It gave them self-esteem,’’ Davis said at the time.

“I shall always remember his goal to have black students achieve at high academic levels. He did many things to make it possible for them to become high achievers,” said Robert Safransky, a longtime colleague in the Pinellas County school district.

Self-esteem was a value Davis tried to instill in youngsters in many ways. Toward that end, he founded Ebony Scholars in 1984 as a motivational tool. The organization targeted elementary school pupils who were maintaining a high-grade average. If the youngsters carried a 3.0 by the time they reached high school, they joined the Ebony Scholars Academic Club, which discussed career options, examined college opportunities, and studied social etiquette. They also completed an eight-week Toastmasters International youth leadership program to develop their communication and leadership skills – and each year, graduating seniors received scholarships.

And each year, the graduating luncheon had an emotional impact on Davis. In a program for one of the luncheons, he wrote: “These students become like your own children,” he wrote in a letter included in the program. “You worry about them and pray that they will make the correct choices in their journey through high school. It is a happy sadness as they show that they have become young adults.”

It was that rapport with and affection for his students, plus his personal integrity, that earned Davis widespread respect in the community. He also helped found the African American Voter Registration and Education Committee, a group that pushed through single-member voting districts to give African Americans a better chance at winning elected office.

“Vyrle Davis was a giant among men,” said community leader Gwendolyn Reese. “He was the consummate educator. He was knowledgeable, experienced, and committed to providing a quality education to all students. I respected and admired him.”

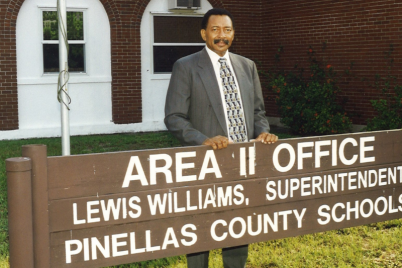

Davis became Pinellas County’s first black area superintendent in 1986. Longtime district employees still recall that he would attend special occasions such as Christmas luncheons and deliver impressive blessings.

He retired in 1995 but continued to push for academic success for students. In 1998, he founded Concerned Organizations for Quality Education for Black Students (COQEBS).

“There were some great years and some good kids,” he said in 2007. “I just look back over my career, and I’m so happy things have been done. And people have been so good to me.”

Safransky worked with Davis on AAVREC, COQEBS and Ebony Scholars, even after he began struggling with Parkinson’s Disease.

“Even though his physical disability challenged his ability to function as well as before, he still performed at a very high level,” Safransky said. “He also found ways to attract people to become supporters of those three organizations.”

Davis is survived by his wife, Mozelle Davis, the couple’s daughter, Celeste, and a close family friend, Lynnette James Hardy.

“His wife and daughter were tremendous,” said Watson Haynes. “They took time off from work to take care of them. I believe he lived longer than he would have because of their devotion. They made sure he was always dressed up, even at his house, so he would be if someone came over.”

A visitation will be held Friday, Feb. 8, at St. Petersburg High School, and a service will be held at 11 a.m. Saturday, Feb. 9, at First Unity Church, 460 46th Ave. N.