With its sunny beach, laid-back atmosphere and LGBTQIA+ friendliness, does the City of Gulfport hide a dark past?

BY JAMES SCHNUR, The Gabber

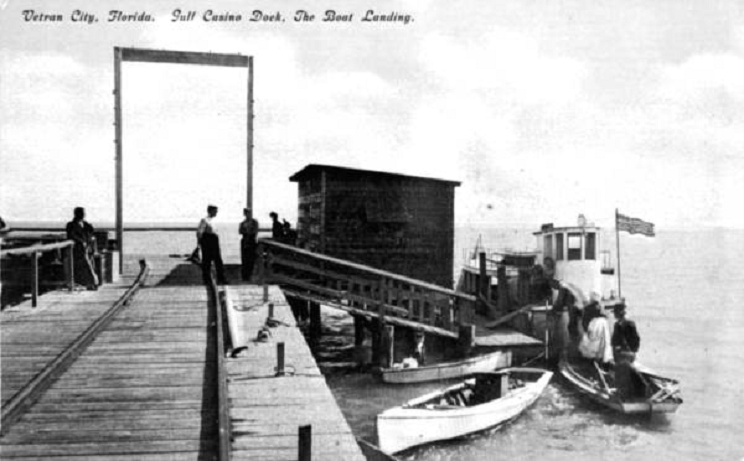

Long known as the “Gateway to the Gulf,” Gulfport has welcomed visitors and newcomers for more than a century. Pioneers who arrived during the Disston City and Veteran City days before the current city was incorporated in 1910 also enjoyed fishing and relaxing along the shoreline.

Underneath the surface, however, a less hospitable reality also existed. Largely lost to the historical record, remembered only piecemeal by some, and increasingly forgotten as time passes, Gulfport’s dark past leaves the city with an unfavorable legacy. As of February 2023, Gulfport is the only municipality in Pinellas County that was once considered a “sundown town,” according to the History and Social Justice Website, a nationally recognized resource hosted by Tougaloo College.

An unwelcoming legacy

Sundown towns existed throughout the United States during the 19th and 20th centuries. These communities used a variety of tactics to encode and enforce segregation. Some localities passed ordinances, others posted signs as a warning to outsiders, and many enforced unofficial or unwritten restrictions through intimidation and threats of violence.

Passengers on streetcars that reached Veteran City (now Gulfport) sat in segregated seating arrangements. | Florida Memory

The most brazen settlements included signs at the town or city limits with a stern warning. The wording varied slightly but often used a racist or derogatory term, along with a warning to those targeted, such as, “Don’t Let The Sun Go Down On You.” In Florida, as well as much of the South and Midwest, Black Americans became obvious targets. In some states, Asians, Jews, Mexicans, and Native Americans also faced similar warnings.

Sociologist James W. Loewen wrote the first book-length study of this phenomenon. Published in 2005, Sundown Towns: A Hidden Dimension of American Racism shed light on this practice where communities used both legal and extrajudicial tactics to prevent certain people from visiting or living in particular areas.

Inconsistent criteria

Deeming a community a “sundown town” involves more than reviewing local ordinances and regulations, especially in Florida. Until the mid-20th century, Florida’s municipalities lacked “home rule,” the ability to enact ordinances or regulations at the local level without legislative consent. Segregation laws and policies from Tallahassee did the “dirty work,” allowing city officials to exclude people without passing local ordinances.

In his exhaustive study, Loewen found little direct evidence implicating Florida communities as sundown towns. He did not mention Gulfport, though he asserted that many larger cities in peninsular Florida – including Tampa and St. Petersburg – had historically experienced some of “the highest levels of residential segregation in America.”

Streetcars, such as this one on Central Avenue at 4th Street in St. Petersburg, had segregated seating on the duration of their routes into Gulfport. | USF Digital Collections

Loewen passed away in 2021. Tougaloo College, a private, historically Black college in Mississippi, continues Loewen’s work by maintaining a database of known and suspected sundown towns.

Gulfport joined Tougaloo’s list of sundown towns after a January 2015 article in Creative Loafing by The Gabber’s current owner and publisher Cathy Salustri Loper addressed the topic. Since then, additional evidence has reconfirmed Gulfport’s legacy.

When did Gulfport begin enforcing ‘sundown town?’

It’s still unclear when, exactly, Gulfport officials quietly began to enforce “sundown town” exclusions. John Donaldson and his wife, Anna Germain, became the first permanent Black residents of lower Pinellas in 1868, living a little east of present-day Gulfport. Though few records exist, it appears this family interacted peacefully with pioneers in the area.

Blacks occasionally fished and picnicked along Boca Ciega Bay near the site of Gulfport’s beach in the early 1900s. These visits occurred during daylight hours and away from white-owned establishments. For example, a May 1906 Emancipation Day picnic near the waterfront in Veteran City attracted Blacks from St. Petersburg, Tampa, and Manatee County. Whites monitored this event, which peacefully ended – before sundown.

The arrival of the streetcar line that connected St. Petersburg to Veteran City allowed for an easy commute for those from the Sunshine City who wanted to visit the Casino or take a passenger boat to Pass-a-Grille before bridges connected the mainland and Gulf Beaches.

Although the number of Black passengers who took the streetcar between St. Petersburg and Gulfport before service ended in May 1949 is unknown, one thing is certain: Police enforced St. Petersburg’s segregation rules outside of the city limits.

Section 354 of the 1917 revised ordinances of St. Petersburg required mandatory separation of white and non-white passengers. Conductors who failed to enforce separate seating on any St. Petersburg streetcar line, even within Gulfport’s municipal limits, faced a $50 fine and possible imprisonment for failing to do their job.

Gulfport bathing beach battle

Now a nature preserve along Boca Ciega Bay, St. Petersburg once hoped to create a segregated beach for Blacks in what is now the South Pasadena Habitat Extension. | James Schnur

Gulfport officials never codified sundown racial restrictions into any ordinance or government document known to exist today. However, they tacitly embraced this unwritten regulation with unwavering resolve. Discussions about a possible swimming beach for Black residents of St. Petersburg in 1937 led a Gulfport councilmember and former mayor at the time to act and speak on behalf of the city and the desire to preserve its status as a sundown town.

During the early 1900s, a majority of white St. Petersburg residents condemned any plan to open a swimming area for that city’s Black community. Mayors such as Al Lang and Noel Mitchell tried unsuccessfully to create a segregated swimming spot along Tampa Bay in then-remote areas of Bayboro Harbor in 1916 and 1920.

Protecting St. Pete segregation

By the late 1920s, an all-white group known as the Southside Improvement and Protective Association condemned efforts to allow Black people to have a public beach. This informal group reappeared on and off for the next few decades. They protested attempts by Black people to live outside of the segregated Gas Plant and Methodist Town communities or attend white schools. Members hoped to limit any integration into northside neighborhoods.

Group representatives held rallies and flooded public meetings condemning any attempt to allow Black residents to set foot in Tampa Bay. They even compelled police to arrest Charles Lester Harvey – a developer of the Bayboro area – when he allowed Black people to enter the water from his private property at 15th Avenue Southeast during the summer of 1929.

In early 1937, city leaders in St. Petersburg looked for a remote place beyond the city limits to create a bathing beach for Black residents. One site they considered sat immediately east of where the Corey Causeway touches the mainland, now home to the South Pasadena Habitat Extension, near Shore Drive South. At the time, nobody lived within a half-mile of that location.

Gulfport’s leaders respond

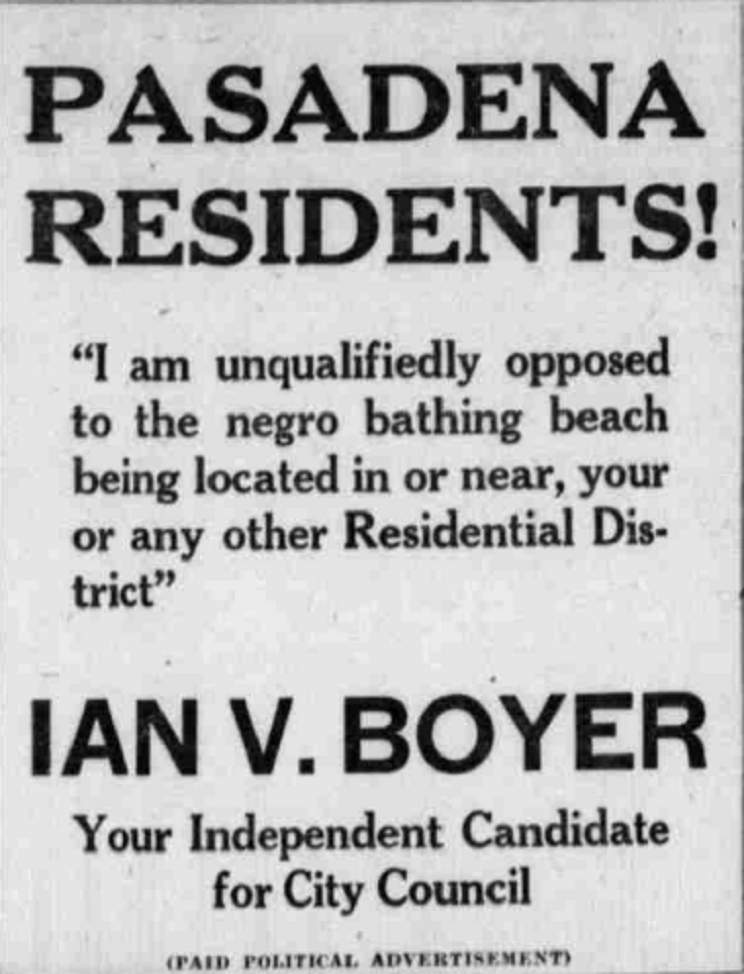

Hearing rumors of this possible plan for a bathing beach, Andrew E. Potter – a former Gulfport mayor – joined a lawsuit to keep St. Petersburg from gaining management of this property. St. Petersburg and Gulfport segregationists expressed their displeasure, making the oft-repeated claim that nearby property values would plummet if St. Petersburg opened a bathing beach near the Corey Causeway.

Walter P. Fuller, a noted developer in Pasadena and western St. Petersburg and a state representative at the time, tried unsuccessfully to get his colleagues in Tallahassee to pass a bill during the 1937 legislative session that would have allowed Gulfport to annex the land. Fuller’s proposed legislation would have had the effect of allowing whites-only access.

Speaking the ‘truth’

In mid-May 1937, Bruno Beckhard, a member of the Gulfport town council, put into words what was known and accepted but seldom spoken. Calling the proposed bathing beach a “betrayal of the town of Gulfport,” Beckhard told a reporter for the St. Petersburg Times (now Tampa Bay Times) that Gulfport’s city council had discussed concerns about how the creation of a “Negro playground” at this undeveloped beach would adversely affect Gulfport.

Beckhard’s statement that appeared in the May 17 issue of the Times stated the commission’s consensus: “In the first place Gulfport has never receded from the position it took when most of the men were fishing and women and children were left alone, that no Negroes would be allowed within the town limits after sundown. This is not a matter of statute; it is merely a condition that no St. Petersburg Negro questions.”

The plan to create a swimming beach for Blacks near Corey Causeway became a campaign issue in St. Petersburg’s 1937 elections. | Google News Archive/Fair Use

Amplifying the concerns of nearby beach settlements as well, Beckhard added, “We in Gulfport cannot help feeling that St. Petersburg, as the largest of the group of Pinellas communities, has betrayed or shown a willingness to betray the rest of us” with this proposal.

Additional newspaper coverage during late May and early June 1937 demonstrated that Gulfport leaders wanted the proposal stopped at all costs to keep out “undesirable elements.” St. Petersburg’s leaders abandoned the bathing beach proposal in June 1937.

Gulfport’s existence as a “sundown town” continued long after this incident. Next week, we will explore additional examples of Gulfport and other Pinellas municipalities maintaining patterns of purposeful exclusion.

This article was originally published in The Gabber on March 17, 2023.

I remember my parents speaking about Gulfport when I was a young girl. They said you must not be caught there after sundown. If you as a Black person worked there, your ‘boss’ had to get you out of there before sundown, even if it meant driving you across the city limits into St. Pete. My Mom spoke of hangings of Black folk in Gulfport. I was well into my adult years before ever going there.

Is it safer now?