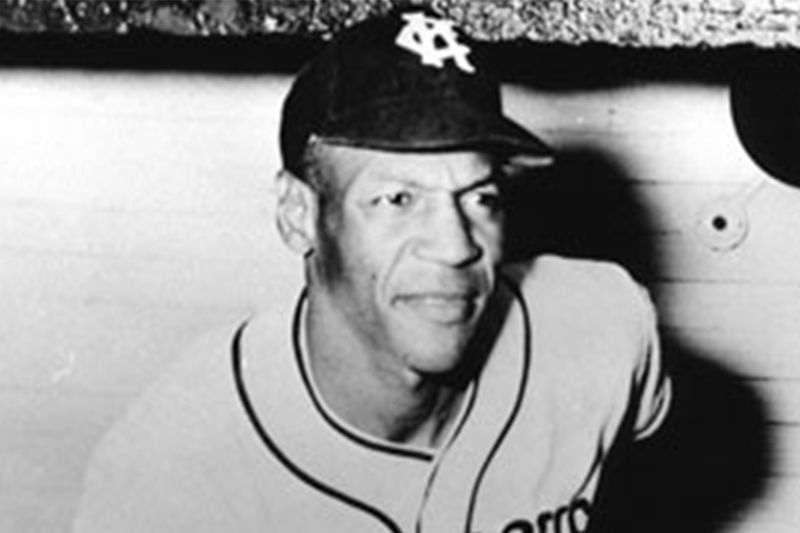

Buck O’Neil took the field as a Cannibal Giant very early in his career.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

In today’s clamorous climate of change, the shouts to end all things racist have finally reached the ears of the National Football League team based in our nation’s capital.

It took nearly nine decades — count ’em, nine! — but the Washington team has finally decided that it may not be the best idea to keep a nickname that doubles as a despicably racist epithet. The “Washington Redskins” are now history, and though the team has settled on a new moniker, it has not revealed it just yet.

Wanting the new name to reflect their proud heritage and their patriotic accomplishments, Navajo Nation members are pushing for Code Talkers to replace Redskins. The term “code talkers” refers to the Navajo servicemen who used their native language to secretly transmit communications with great success during World War II.

Whatever the new name, we can all agree it’s been a long time coming. Even St. John’s University changed its name from the offensive Redmen to Red Storm back in 1994. The University of Massachusetts also called the Redmen at one point, eventually responded to pleas from a Native American group and agreed to change its school nickname, becoming the Minutemen — way back in 1972!

But Native Americans haven’t been the only ones insulted by racially defamatory team names.

Picture the following scenario: you’re at a high school football stadium on a crisp, fall evening. The very air is ripe with anticipation, as the crowd and cheerleaders await the home team to take the field. Suddenly, in a collective burst of energy the players sprint out onto the turf, and you — along with screaming students, their younger siblings, football parents and old alumni — wildly cheer for these young athletes, black and white alike, with the chant: “Go, you Coons!”

As unfathomable as that scene is, a relatively short time ago, it could’ve played out in Frisco, Texas. The team name of Frisco High School had been the Fighting Coons since the 1920s and reportedly was suggested by a former student in honor of his pet raccoon. It took about 80 years before officials at this school admitted that it might be in poor taste to retain a moniker that also is an outright slur, and in 2002 its school board changed the name to the Fighting Raccoons.

I have to believe that in all those decades — most through the Jim Crow era — there must’ve been more than a few uncomfortable moments among black students, black teachers and other school employees in that high school as they saw the word “coon” emblazoned on walls, signs or anywhere else on campus.

Yes, the “coon” here refers to the animal, but who is to say for sure that the vile wordplay wasn’t intentional and meant as a sick joke? Even supposing it was an innocent act to adopt the nickname “Coons” back in the 1920s, why then was it tolerated all the way into the 21st century? If we assume there were calls from the African-American community for the school to change the name, then we should assume these pleas were shouted down or ignored for far too long.

Though the Frisco Fighting Coons eventually did right the deplorable wrong, some teams of yore will forever be known by their offensive monikers.

Although some Negro League teams used the word “Black” in their names to differentiate them from their white counterparts — such as the Birmingham Black Barons and the New York Black Yankees — teams like the Ethiopian Clowns stood apart.

It’s anyone’s guess why white founder Syd Pollock settled on such an outrageous name, especially since the team got its start in Florida. Since it was the 1930s and Ethiopia was embroiled in a conflict with Italy, he may have gotten the idea from the newspapers. Or, as a business-savvy showman, Pollock perhaps sought to underscore the supposed African roots of the black players. It wasn’t enough that they were a Negro League baseball team, but they had to be an exotic-sounding Negro team as well, so this connection to the Dark Continent fit the bill.

This scheme didn’t stop at the team’s name. A Greenville, Pa., newspaper from 1936 touted the arrival of the visiting team: “Sporting clown suits, and with ‘bushy’ red hair, the Ethiopian warriors are said to present a weird appearance on the ball field, but they are also said to be capable of playing a smart, aggressive brand of baseball as well.”

Directly under the article’s heading, which read, “Ethiopian Clowns to exhibit wares here,” was a photo of the team posing in wigs and “whiteface” while holding bats. They were flanked by images of two African warriors with headdresses holding spears and large, oblong shields. As a final insult, the banner underneath the team photo called the Clowns a “baseball tribe.”

The Clowns were primarily a barnstorming team that became known for their comedic antics, employing elements of vaudeville and slapstick as part of the show. Pollock promoted these games in black newspapers such as the Chicago Defender, which advertised a July 4 game at Comiskey Park by promising “unmatched comedy, stellar big league baseball.”

By the 1940s, the same decade that saw Major League baseball integrated, many black newspapers shied away from covering the Clowns as they saw them as an embarrassment more than anything else. This roving ball club would be renamed the Cincinnati Clowns and, ultimately, the Indianapolis Clowns, and continued to play long after the other black barnstorming and teams faded away.

However, when it came down to it, they were no slouches as ballplayers and could hold their own on the diamond against most teams. But the team must have found it impossible to be judged by its quality of play when the lineup cards featured such absurdly comical names as King Tut, Tarzan, Abbadaba, Wahoo and Haile Selassie, the Emperor of Ethiopia.

As debasing as it was to call a team of grown men the Clowns and as humiliating it was to refer to its American players as a “baseball tribe” ostensibly from Africa, the low watermark for any team name has to be the Zulu Cannibal Giants.

Like the Clowns, the Cannibal Giants, formed in 1934 in Louisville, Ky., was presented as another gimmicky black baseball club. A big difference was that this team had to play the “jungle man” part through and through.

For maximum effect, they took the field shirtless and barefoot, wearing only grass skirts. They also smeared their faces and bodies with African tribal paint, and when they stepped up to the plate, they used special bats designed to resemble Ethiopian war clubs.

They, too, didn’t use their real names but “native” sounding sobriquets such as Limpopo, Rufigi, Kangkol, Kalahare and Tankafu. Worse, as part of their performance, they often staged fights with spears and shields on the field. Who knows, maybe the winners even made a show of eating the losers’ flesh, you know, in case some fans might’ve felt cheated if their price of admission didn’t include some form of cannibalism.

The Clowns and Cannibal Giants might’ve been baseball’s answer to the Harlem Globetrotters — who combined showmanship and comedy to entertain — but let’s not discount the real prowess many of these players possessed. Future home run king Hank Aaron was a Clown for a short period, and even Negro League great Buck O’Neil took the field as a Cannibal Giant very early in his career. He didn’t exactly recall those days fondly as he wrote in his autobiography: “Looking back on it, the idea of playing with the Cannibal Giants was very demeaning.”

Unfortunately, derogatory stereotypes exist in the history of our sports and in certain team nicknames. And although the Washington football team held on to its offensive moniker for too long, it does deserve praise for finally tossing it out and moving forward.

And at least their players never had to masquerade as “savages” and run onto the gridiron in moccasins, feathered headdresses and war paint.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com