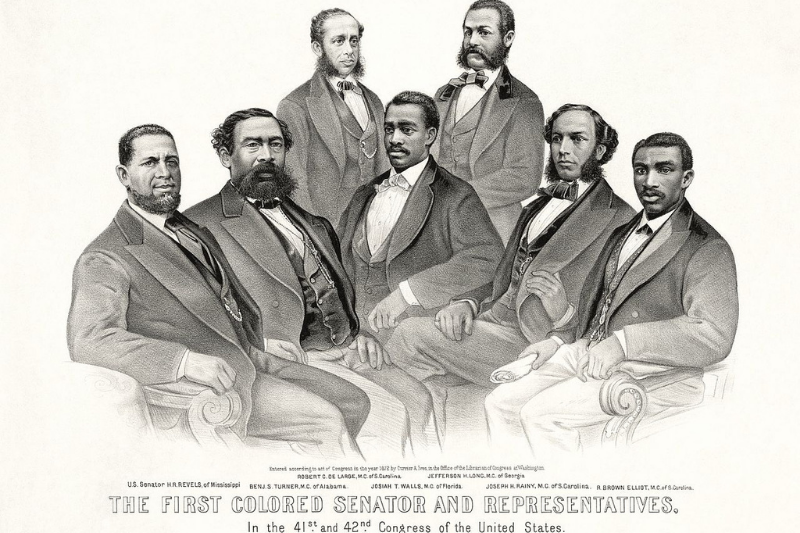

The first African Americans to serve in Congress were Republicans elected during the Reconstruction Era. After the 13th and 14th Amendments granted freedom and citizenship to enslaved people, freedmen gained political representation in the Southern United States for the first time. In response to the growing numbers of Black statesmen and politicians, White Democrats turned to violence and intimidation to regain their political power.

Dear Editor:

Watching the public comment section during the school board meetings across the country, people might be disgusted or inspired depending on where they land on the issues being discussed. This phenomenon took off last school year to fight against mask mandates to “save our children” and has now morphed into the critical race theory conversation.

Local school districts are not unique in this. Local activist groups have been creatively and deliberately misaligning anything they can find on the board agendas with critical race theory. For example, at a recent local board meeting, speakers falsely claimed the district’s teacher evaluation tool (Learning Sciences International’s iObservation) and a program that engages students in leadership development (Stephen Covey’s “Leader in Me”) as examples of critical race theory.

These folks either really believe what they are saying or recognize that they can get more traction for the “issues” by race-baiting. Whatever the case, they are part of a long line of white resistance to perceived Black progress.

One such example is after the Civil War and slavery ended. The Reconstruction Era was meant to expand Black people’s citizenship and force Southern slave states to engage in the process of integrating formerly enslaved Black people into society. During this era, formerly enslaved Black people won elections, served in Congress, started schools, started businesses, created thriving towns, and succeeded in a multitude of other ways.

From Klan terrorism to prejudicial media coverage to white citizens’ outrage to the actions of congress members (including those who had formerly seceded to the Confederacy), the Reconstruction era was short-lived. Reconstruction ended, and much of the progress Black people made in that time was reversed. In fact, it would be 97 years before another Black person became a senator.

In her 2016 book, “White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide,” Carol Anderson wrote: “The trigger for white rage, inevitably, is black advancement. It is not the mere presence of black people that is the problem; rather, it is Blackness with ambition, with drive, with purpose, with aspirations, and with demands for full and equal citizenship. It is Blackness that refuses to accept subjugation, to give up.”

I see the watering down of and dismantling of equity-centered programming throughout the nation. This makes me wonder if, here too, we will allow white rage to be the impetus for decreasing the demand for full and equal Black citizenship by watering down intentional efforts to create equitable access to education for Black students.

Michelle Fignolé