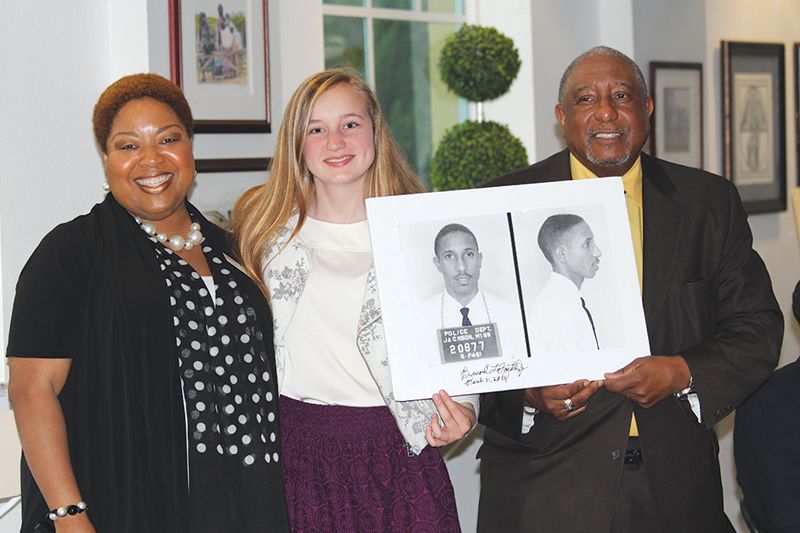

The community gathered at Dr. Carter Woodson African American Museum as the YWCA of Tampa Bay held a community conversation featuring longtime civil rights leader and global authority on nonviolent social change, Dr. Bernard LaFayette.

His loveable and outgoing personality was on display as he went about engaging the room with stories of a lifetime combating racism.

“Growing up in that time for us was frightening, sometimes amazing, sometimes baffling,” LaFayette said as he described the nonviolent direct action campaigns he participated in during the 50s and 60s, the era of Martin Luther King.

A key player in the Civil Rights Movement, LaFayette held the attention of the young, the old, the black and the white, as he recounted his parent’s reaction when he first decided to join the civil rights movement.

“We wrote out our wills because we didn’t know whether we were going to come back,” he said joking that his father had more children just in case he didn’t return. “They weren’t expecting me to come back.”

LaFayette learned about nonviolence in Nashville, and then went on to the Freedom Rides. He joined in on sit-ins in the Music City where he boasts desegregating lunch counters downtown in just three months. It didn’t take long to do the same with the city’s movie theaters as well.

But his days of working in the movement alongside Dr. King were some of his fondest.

“When I got to work with him, that was just a fantastic experience,” LaFayette said of the civil rights legend. “He was able to deal with managing the conflict among the folk.”

A trait LaFayette admired. But when he was working on a press statement in 1968, he met up with Dr. King for the last time. Sitting in a hotel room, LaFayette in his 20s barely a man, both discussed the future of the movement.

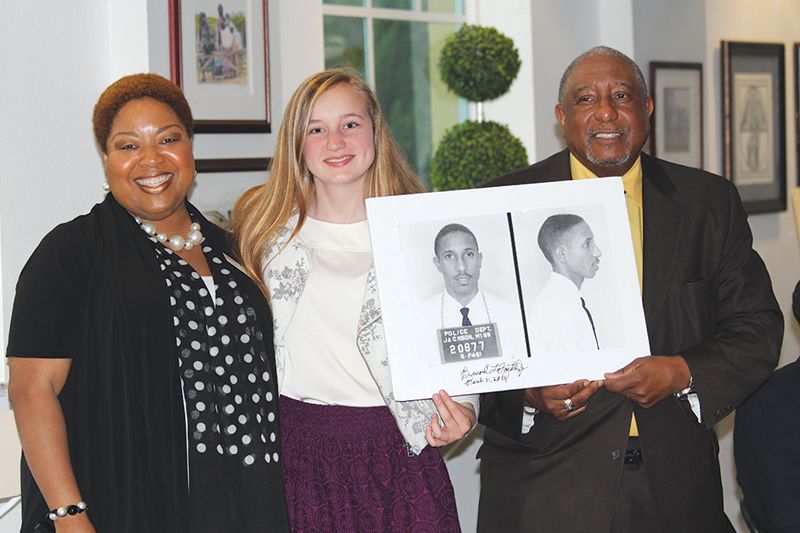

Dr. Bernard LaFayette, left, & Dr. Gregory Padgett

King was sending LaFayette to the Washington, D.C. to open a campaign office for King’s Poor People’s Campaign. And as he was heading out excited about the future of the movement, LaFayette had no idea that this would be the last time he saw King, nor that his last words to him would drive nearly all his future endeavors.

“‘The next movement we’re going to have is to internationalize and institutionalize nonviolence’,” LaFayette recalled King saying. Five hours later as LaFayette’s plane touched down in Washington, D.C., Martin Luther King was killed.

And although violence did break out in some parts of the country, LaFayette recalls a different side of the tragedy. A reporter breaking down on the phone, his weeping sincere.

“You didn’t have to tell me Martin Luther King was dead,” LaFayette said. “I heard it through the tears and groans of the white reporter.”

LaFayette who had put his college career on hold, taking on projects such as raising bail money for activists finding themselves locked up for what he suggests were trumped up charges, wanted to be the director of one of the many voter registration projects underway at the time. But when he returned from his work acquiring funds, there didn’t seem to be anywhere to put him.

But Selma, Ala. had been a sore spot on the movement’s back. After sending two teams of Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) workers there, civil rights activists had given up at that location. LaFayette was interested in organizing and leading the black community in voter registration, so he was asked if he wanted to head on down and take a look at the area.

“I said no,” LaFayette laughed with his admiring audience, “I don’t want to take a look at it – I’ll take it.”

From his schooling, LaFayette knew research was an important factor in decision making, so he set about learning about not only the area, but the folks that lived there, primarily, the white men and women. Placing himself in the mindset of the townspeople, LaFayette was able to succeed where others had failed.

Over the years, he has gone on to distribute the message of nonviolence and led trainings in some of the Chicago area’s toughest gangs. He has been a principal, appointed for his work with troubled youths, using the message of nonviolence to calm the masses and instill the idea of turning the other cheek.

“We had to teach them that real courage was not holding your gun. Real courage was holding your temper,” explained LaFayette. “That’s what courage is all about. Holding yourself together when folks get mad at you for no reason, say things you don’t like.”

All over the world, LaFayette has spread his message of nonviolence. He started a prison program in upstate New York when a prison riot was on the verge of breaking out. The inmates were trained on how to become trainers themselves and spread the message of nonviolent interaction. Now the program is in Florida and being used as an alternative to violence program. LaFayette designed the curriculum being used today back in 1975.

Now with the program in roughly 50 countries around the world and 30 states in the US, prison riots are almost unheard of.

Active in the NAACP at the ripe age of just 15, LaFayette has had a long career of fighting for African-American rights and is still serving as messenger of King’s dream.

His dedication to the Civil Rights Movement continues to be fought today as he spreads the word of interacting peacefully and solving conflicts, rather related to race or various other personal disruptions, in a nonviolent manner. LaFayette’s humbleness and his ability to get his message across through humor serve as an inspiration to future generations to continue to spread the word of nonviolence.

“Conflict, it’s not going to go away, but you have to learn how to manage it, that’s key,” he said stating you just can’t say you tried and then pick up a weapon. “If you learn what nonviolence is all about, it will take you anywhere you want to go.”

Bernard LaFayette’s book, “In Peace and Freedom: My Journey in Selma,” can be found online at amazon.com.

Post Views:

13,872

Now this should be the making of a movie. A true authentic black american hero. Imagine that he was active in the NAACP at the ripe age of just 15, yet today, you would find few 15 year olds who could tell you much about the NAACP.