BY JON WILSON, Columnist

ST. PETERSBURG — A Mecca for baseball’s spring training since 1914, St. Petersburg in 1961 became a focal point in the battle to end discrimination in the lodging of black and white players.

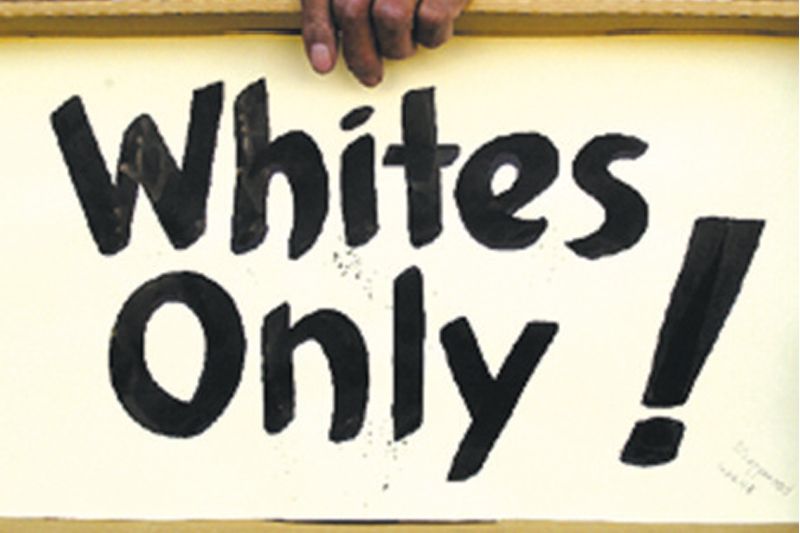

Jackie Robinson broke the Major League’s color barrier in 1947. But as more African-American players began to be signed by the big leagues, an old custom prevailed in St. Petersburg and in 10 other training sites throughout Florida.

Eighteen teams trained in the Sunshine State, and all except the Los Angeles Dodgers housed their African-American players in segregated housing. In St. Petersburg, white players for the St. Louis Cardinals and New York Yankees typically stayed at such posh establishments as the Vinoy and Soreno hotels downtown. Because of segregation customs, black players stayed in homes, apartments and boarding houses in the community.

It wasn’t that the accommodations for the black players were substandard. But the separation from their teammates was one more insult in a system that also denied the players equal access to many amenities such as restaurants, recreational facilities and movie theaters.

The situation began to change in 1961. Black players were excluded from St. Petersburg’s annual “Salute to Baseball” breakfast. The omission may or may not have been deliberate. But black players, given the era’s racial climate, felt slighted.

“I think I’m a gentleman and can conduct myself properly, “ said St. Louis Cardinals’ first baseman Bill White.

He and others used the occurrence as a starting point to bring about change.

“This thing keeps gnawing at my heart,” White was quoted in the Pittsburgh Courier. “When will we be made to feel like humans?”

Doctors Ralph Wimbish and Robert Swain were civil rights leaders who also housed African-American players. At about the same time, they decided to take on baseball’s housing segregation. Wimbish had helped desegregate the city’s lunch counters and said he couldn’t square his activism in other areas if he didn’t make a stand for the players. Wimbish told newspaper reporters he would no longer house Elston Howard, the Yankee’s all-star catcher, and he asked Yankees and Cardinals management to join him in calling for an end to segregation.

The state NAACP backed Wimbish, but St. Petersburg business leaders and other officials didn’t like it. They voiced opposition. But the ball was already rolling. In March of that year, the Chicago White Sox canceled their hotel in Miami after the hotel refused to accept the team’s black players during an exhibition game. Other teams took similar stands, and the spring training issue became a national news story. Perhaps to avoid a deluge of bad publicity, most Florida ballparks ended discriminatory practices, and by the following spring, most black players were able to stay with their white teammates in the same hotels.

Officials in St. Petersburg worked to find accommodations in hotels other than the Soreno or Vinoy.

Meanwhile, the Yankees moved to Fort Lauderdale, but it was unclear whether racial discrimination was a reason. Team officials said the move had been in the planning stages for several years.

The New York Mets came to town in 1962. Not every landlord who had provided segregated lodging supported Wimbish’s and Swain’s initiative. Nonetheless, the season of ‘61 was an important turning point in St. Petersburg’s — and Florida’s — journey toward equality for all.