The Parker Watson lynching brought outcries from a number of people including St. Petersburg ministers.

By Gwendolyn Reese

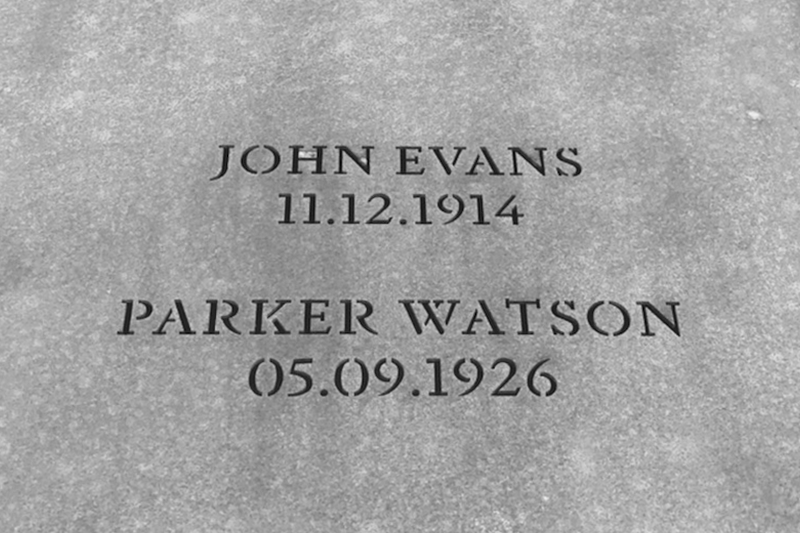

Parker Watson was lynched at the hands of a group of armed men wearing masks after being taken from three police officers on the evening of May 9, 1926. The officers were taking him to Clearwater, the site of the county jail.

His body was found along an isolated road on Monday morning. He had been shot and some acid or chemical poured on his face. According to the article, “Historical Lynchings: The Disgraceful Evil,” Watson had committed nine robberies.

Unlike the lynching of John Evans in 1914 when public officials and “upstanding” citizens were members of the lynch mob and were said to have planned it the night before, the Watson lynching brought outcries from a number of people including St. Petersburg ministers.

Herman Dann, president of the state chamber, asked Governor John Martin to conduct a thorough investigation saying, “the fair name of the state was at stake and that the blot must be wiped out.”

The sheriff vowed to conduct a thorough investigation of his officers and the St. Petersburg Police Department to determine if either agency had been involved. During a special session, the county commission condemned the lynching in a resolution and offered a reward of $1,000 for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the guilty parties.

An article in the Ft. Myers Press reported that St. Petersburg Mayor C. M. Blanc asked the governor for aid in the investigation. This article also alleged that Watson was being “held on a charge of attacking white women to steal their purses.”

It was reported in the May 15, 1926, edition of the St. Petersburg Times that Judge Freeman P. Lane was dissatisfied with the report submitted by a grand jury to the circuit court after investigating the Watson lynching. The judge ordered the grand jury held over to continue the probe into the lynching based on the uncovering of clues regarding the perpetrators. The judge reminded the grand jury of the negative impact lynchings would have, especially with the tourist industry.

The article includes an allegation made by H. B. Smith, chief of detectives with the St. Petersburg police force. He later retracted the allegation saying that “he was only joking.” The allegation was concerning the origin of a white scar on the face of Watson believed to be the result of torture using carbolic acid.

Smith claimed the scar was caused by the Negro undertakers while removing facial hairs using a chemical preparation. The undertakers, however, were adamant in asserting, “The white scar was on the face before the body was taken from the spot where he was found.”

The Orlando Sentinel stated: “Rarely has this city been so stirred as it has over the death of the negro [sic], whose body was found with five bullet holes in it, and what appeared to be acid stains on his face.”

The Sentinel article also stated that “there is a theory that some persons, believing the negro [sic] to know the location of a large amount of stolen goods, took him and applied acid to his face in order to get him to reveal the hiding place, and when this failed, killed him.”

The article went on to say that there was no explanation why he was handcuffed when taken from the officers but there were no handcuffs on him when he was found. He was said to have a silver dollar clutched tightly in one hand when found and there were several coins scattered around him.

The perpetrators were never identified or prosecuted.

The practice of lynching originated on the American frontier in the 18th century. Colonel Charles Lynch first employed the dispensation of “private justice” against horse thieves and common criminals in western Virginia. Lynching continued well into the 20th century as a way of controlling blacks, immigrants and even political radicals.

According to the NAACP, between 1900 and 1930, Florida had the “highest ratio of lynchings to minority populations” of any state in the country and Tampa had the largest number of any Florida city or county during the same period.

Two hundred-fifty lynchings occurred in Florida from March 1882 to April 1930. Of that number, 18 were white, seven were listed as unknown and 225 were black. Five were black females; six genders unknown and 239 were black men.

Senator Darryl Rouson and the African American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg, FL, Inc. are heading a coalition of community organizations to bring Pinellas County’s lynching monument home.

The Lynching Marker Project is part of the Equal Justice Initiative’s effort to recognize the victims of lynching, acknowledge the horrors of racial terror lynchings and help cities to confront and recover by acknowledging, discussing and addressing this tragic history.

If you are interested in being involved in the Lynching Marker Project or would like more information, call (727) 537-0449.

Sources:

St. Petersburg Times, May 12, 14 and 22 1926 editions.

Ft. Myers Press, May 21, 1926.

Tampa Bay History 06/02, University of South Florida, College of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Dept. of History.

Orlando Sentinel, May 11, 1926

Historical Lynchings: The Disgraceful Evil, This Cruel War