The life and legacy of Elder Jordan

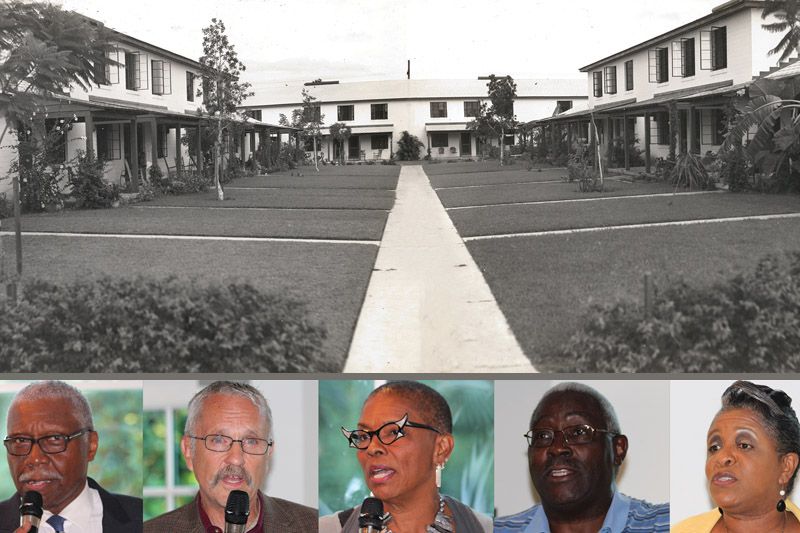

Elder Jordan is known for erecting, along with his sons, the Jordan dance hall, which is now known as the Manhattan Casino. He was also responsible for the construction of houses and establishing a bus line and a beach for African Americans during the time of segregation here in St. Petersburg.

Elder Jordan is known for erecting, along with his sons, the Jordan dance hall, which is now known as the Manhattan Casino. He was also responsible for the construction of houses and establishing a bus line and a beach for African Americans during the time of segregation here in St. Petersburg. Indeed his grandfather started out peddling fruit, sometimes delivering door-to-door. He was even known to own his own livery stable. But it was Elder Jordan’s demeanor and apt for business that earned him respect amongst the races during a time when racial tensions were high and segregation was the norm.

Indeed his grandfather started out peddling fruit, sometimes delivering door-to-door. He was even known to own his own livery stable. But it was Elder Jordan’s demeanor and apt for business that earned him respect amongst the races during a time when racial tensions were high and segregation was the norm.Notifications