Annie Dabbs works with a small group of volunteers to try and maintain Rose Cemetery (formerly Rose Hill Cemetery), without any support from the City of Tarpon Springs.

BY J.A. JONES, Staff Writer

TARPON SPRINGS – Annie Doris Dabbs’ name is synonymous with Black history in Tarpon Springs. So much so that she was recently featured in Elizabeth Indianos’ history play “This Blessed Plot, This Earth” and mural of the same name, which graces the theater’s wall. Of all the characters featured in the play and the mural, Dabbs is the only one still living.

Her home is a repository for hundreds of photographs and mementos of growing up in Tarpon Springs. This month, she brought her carefully designed project boards and framed photos of the African Americans – students, teachers, church folk, businesspeople – that lived, worked, worshiped, and were educated in Tarpon to the Tarpon Springs Area Historical Society.

Thanks to Dabbs, the Historical Society, located in the Historic Train Depot Museum, has a Black History Month exhibit.

Dabbs is a charter member and serves on the Tarpon Springs Historical Society board and second president of the city’s Historic Preservation board. Having watched how historic preservation of old buildings happens, she brought her desire to erect a museum to preserve the history of Black Tarpon to the city commission.

She shared her opinion that a church in the Union Academy neighborhood that was slated for demolition would be the perfect spot for a permanent home for such a museum – to “keep our history alive,” she noted.

Instead, the city proceeded to tear the building down instead – one of just a number of structures in the Union Academy Neighborhood the city has chosen to demolish. When asked why the city moved forward on the demolition of the building that Dabbs knew could have been restored, the educator-turned-historian shrugged, sighing:

“Some of the commissioners voted not to do anything. I think it’s unfair because you can’t hide all the history. It’s just like the days of segregation; some parents don’t want their children to know what happened, but it happened. Our history must be told.”

Annie Dabbs’ home is a repository for hundreds of photographs and mementos of growing up in Tarpon Springs. This month, she brought her carefully designed project boards and framed photos of the African Americans – students, teachers, church folk, businesspeople – that lived, worked, worshiped, and were educated in Tarpon to the Tarpon Springs Area Historical Society.

She uses the example of the current ignorance of the African-American contribution to Tarpon’s largest industry, its sponge production. “If you go downtown and ask the first visitor, ‘How did the sponge industry start,’ they’re going to say, ‘Greeks.’ That’s not true. Guess how the sponge industry started? With Black men.

“They didn’t have the diving suits and the helmets and all that,” Dabbs continued. “They had a hook, and they’d be in this little boat, hooking sponge. A man came from Greece and saw it. He went back to Athens, got a group of men, brought over diving suits, a helmet, and took over the sponge industry. Blacks were the first ones to do it.”

Tarpon’s reckoning with its racism of the past, present, and future is a topic Dabbs is careful about in her conversation; her spare shoulders and expressive features reveal more of her discontent at Tarpon’s treatment of its Black citizenry than her words.

Her love for her hometown and her pride in the accomplishments of its African-American citizens are more comfortable topics, and she shares stories of those easily.

Her many photo albums show the people who held the fabric of the proud Black community together. Dabbs herself is one of those people; her service to the community includes an extensive list of activities and social service inside and outside of the Black community.

A long-time member of Mt. Moriah AME Church, Dabbs has served on the boards of the

Shepherd Center of Tarpon, the Union Academy Neighborhood Development Corp,

Habitat for Humanity Pinellas/Pasco and been a Sixth Judicial Circuit Guardian ad Litem and Sun Coast Hospice Advent Health volunteer for many years.

The awards bestowed on her include the City of Tarpon Springs Designation of Volunteer Extraordinaire under Mayor Beverley Billiris, a Certificate of Special Congressional Recognition in recognition of outstanding and valuable service to the community by Congressman Michael Bilirakis, and a Certificate of Appreciation: Tarpon Springs Citizens Academy under Mayor Chris Alahouzos.

She also served on Congressman Gus Bilirakis Advisory Board from 2016-21.

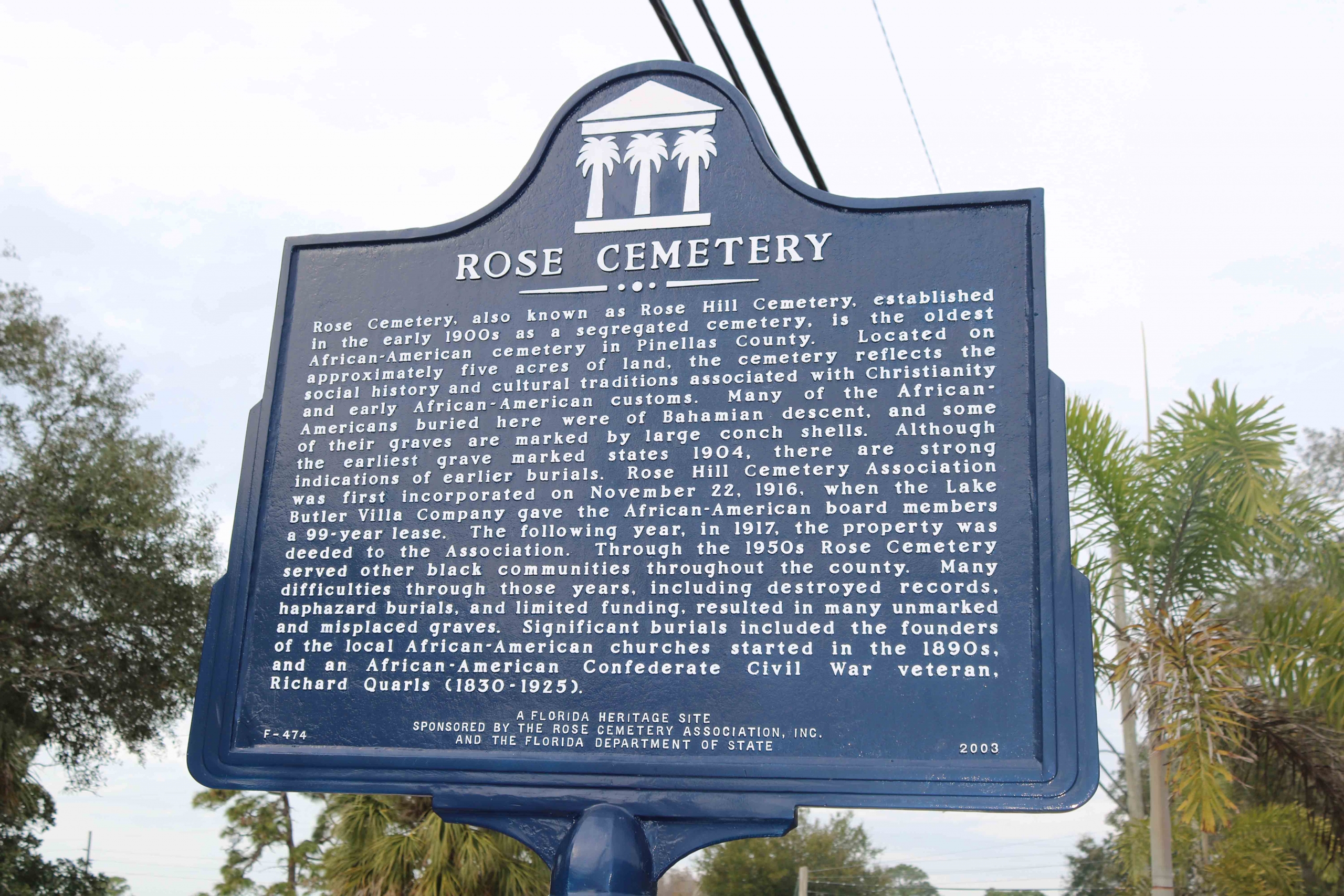

Dabbs’ name is also closely tied to the stewardship of Tarpon’s Rose Cemetery (formerly Rose Hill Cemetery), incorporated as the largest segregated African-American gravesite in the county in 1916 and still providing community members with burial plots today.

The cemetery covers five acres of land right across from city-owned Cycadia Cemetery. Rose Cemetery was once connected to Cycadia, serving as the segregated, all-Black section of the cemetery until a road split the two at some point. In 1917, the property was deeded to the all-Black Rose Hill Cemetery Association in a 99-year lease.

Dabbs’ relationship to Rose Cemetery dates back to when, at age 15, she was asked to take minutes for the cemetery’s board of trustees. Today, at 84 and president of the Rose Cemetery Association, she leads a small band of volunteers in keeping up the large property without much outside support.

While Cycadia is supported by tax dollars and maintained in well-appointed condition by the city, just across the street, Rose struggles with overgrown foliage and trees, garbage tossed by locals, and not enough resources to erect badly needed new gates.

“Cycadia became a city property early on, and thus benefited from city services and upkeep,” Tina Bucuvalas, a former researcher for the city who initiated the National Register applications for Cycadia and Rose cemeteries, shared in 2019. “Due to segregationist policies in the early 20th century, Rose was divided from Cycadia and turned over to the African-American community for upkeep.”

Dabbs works with a small group of volunteers to try and maintain the property without any support from the city. She acknowledged that while Cycadia is no longer segregated, everyone’s tax dollars – Black Tarpon residents as well – go to its upkeep.

However, Rose Cemetery is on its own.

“The Rose cemetery, as they say, is owned by the community. The land was given to the community. The city doesn’t do anything out there. They put a dumpster there because prior to that, people from their area were coming out dumping,” she sighed. “No respect at all. So, the city just put a dumpster out there like that’s a big deal — it’s not.”

Dabbs works with a small group of women to rake and clean up litter and soon hopes to find support for a new gate and much-needed landscaping work.

Part Two of this article continues on Dabbs’ family history and Black Tarpon of yesteryear and today. If you’re interested in supporting the efforts of Rose Cemetery, contact them at (727) 942-8627.