BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

At last, the wait was over.

A longtime fan of the recently departed Chuck Berry, I held in my hands his first album of new material since Jimmy Carter ran the country, disco ruled the airwaves and Daisy Duke sported cut-off shorts on TV, and let me tell you, my excitement was high. I popped in the disc with the Zen clarity that these 10 brand-new tracks would serve as the coda to the life and career of the architect of rock and roll—the final word from the master. I was all ears.

But as I took in one song after the next from this album simply titled “Chuck,” I realized a single, lucid question kept popping into my head: Why, Chuck, why?

***

You can make the argument that not only rock and roll music but teenagers were invented in the 1950s. Chuck Berry was their mouthpiece.

Fast cars, school days, a backbeat you can’t lose, a jukebox blowing a fuse. His words painted vivid pictures of daily life for teens, who were becoming a formidable cultural force of their own in this country with their transistor radios, blue jeans and dance parties.

Charles Edward Anderson Berry, with his middle-class upbringing, wrote songs that spoke directly to them and as a consequence, played no small role in helping to shape a generation. As his jubilant music and lyrics appealed to white youths of the day as well as black, he became one of the first African-American performers to break racial barriers.

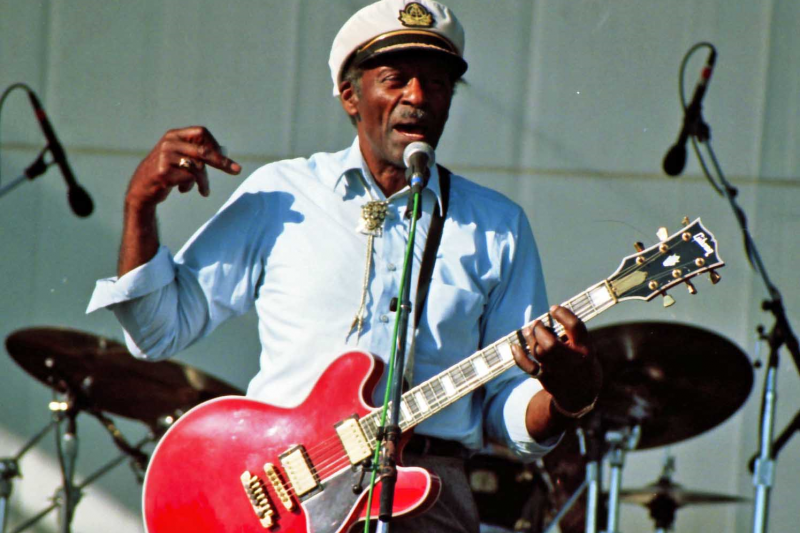

In Berry’s hands, his guitar became a clarion, declaring war on all that had come before and delivering youths from days of old. His unique double-string licks flew from his Gibson sounding brazen and brash, as he bent the strings and molded the rock and roll sound for decades to come.

As if his ringing notes on “School Days,” his fluid riffs on “Carol” and his chugging chops on “Nadine” weren’t enough, his ecstatic playing on the peerless “Johnny B. Goode” alone would’ve secured his place as the patron saint of all rock guitarists.

Yet there would be bumps in this road to rock sainthood, some of them almost insurmountable. As the curtain was closing on the 1950s, the slammer door was about to shut on Berry. On Dec. 23, 1959, he was arrested for violating the Mann Act, specifically transporting a 14-year-old girl across state lines for allegedly “immoral purposes.”

Though Berry protested that he had simply made a legitimate job offer to a girl from Juarez, Mexico, to work at his St. Louis nightclub, the all-white jury ruled against him. He was convicted and between 1960 and 1963 one of the founding fathers of rock became a federal prison inmate.

Though Berry was viewed as a likable, easy-going guy by many before his arrest, after his release from jail he became more surly, bitter and extremely guarded. Once again a free man, he managed to pen such classics as “No Particular Place To Go,” “Promised Land” and “You Never Can Tell.” Yet it was in a noticeably different world that Berry found himself—his own disciples had not only caught up, but were about to lap him.

In time, his signature sound had not only spawned a gazillion emulators but spanned entire continents and oceans, from California surf rock to the British Invasion, from Jimi Hendrix and the Beach Boys to the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. These shaggy-haired harbingers announced the next wave of music, and Berry had already become somewhat of a relic that had not yet begun to gather dust.

Though he put out a handful of studio albums into the 1970s—decent records, to be fair, but none of them knocked the world on its ear—his morphing into a full-blown nostalgia act was complete when he recorded no new material after the release of 1979’s “Rock It.”

Though he put out a handful of studio albums into the 1970s—decent records, to be fair, but none of them knocked the world on its ear—his morphing into a full-blown nostalgia act was complete when he recorded no new material after the release of 1979’s “Rock It.”

Instead, he opted to make the rounds and perform his sock hop rock to aging audiences. Toss into the mix that whenever he did appear live for many one-off shows, far too often he threw together a pick-up band of nobodies to back him.

Perhaps it was an upshot of his post-prison bitterness, but his wary ego apparently couldn’t handle not being the only star on stage. And besides, if anything went wrong and the show suffered, he could always dump blame on the nobodies.

So it went, well into his golden years. He settled in to sing the same old chestnuts about teens and cars even as an octogenarian, going through the motions while strumming away at his guitar less vivaciously with each passing year.

***

Then on his 90th birthday, he came to life. Or at least decided he still had something left to show us, and announced on Oct. 18, 2016, that he’d have a new album coming out—his first in nearly four decades. He’d been working on it for some time and though did manage to ultimately complete it, he didn’t live to see its official release as he went to the great gig in the sky on March 18, 2017.

And during my first run-through of his final work, the pesky question persisted: Why, Chuck? Why’d you wait so long?

In every song on this album, his vocals sound more cocksure and vibrant than they have in any of his concerts of the past few decades, unmistakably projecting: “I’m back, world!” And if he served up guitar licks that stung the very air in his classic tunes, the licks on this album had bite. This was no old-timer croaking his way through a swan song, but a man who’d just done a cannonball into the Fountain of Youth, toweled off, strapped on the ol’ ax and dared everyone around him to keep up.

“Big Boys,” one of the record’s more hard-driving highlights, kicks off with the ever-familiar Chuck riff and doesn’t let up as it features short bursts of exuberant guitar, closing with a particularly wicked, string- bending solo. In the rave-up “Lady B. Goode,” Berry revisits familiar territory, telling about the love interest of…well, take a guess who. And from the catchy rocker “Wonderful Woman” to the bouncy waltz of “3/4 Time (Enchiladas)” to the calypso-flavored “Jamaica Moon,” he injects a newfound zip and zing into every track and sounds like he’s having a blast, to boot!

As I held the last-ever offering of the great Mr. Berry, I mused upon all the musical styles that have come and gone since he decided to pull the plug on recording almost 40 years ago, and of one thing I was certain: songs that made you feel this good would find a place in any decade, period.

Through the eras of synthesizer-driven New Wave music and raucous hair bands in the ‘80s, thug-life rap and garage grunge in the ‘90s all the way to the over-polished, auto-tuned dreck of today, the father of rock had simply stood to the side, crossed his arms and deprived us for far too long.

But when the disc finally came to an end, another even more lucid thought elbowed its way to the front of my mind: Why be down about all that now? He may have taken his sweet time before giving us something fresh, sure. And even though “Chuck” may be his final bow, the man will never truly make an exit.

I tapped the “Play” button again and settled in for another go-around—the first of too many to count. “Oh well look here now, this just makes my day!” he joyously sang in the album’s very first lines.

You said it, Chuck.

To reach Frank Drouzas, email fdrouzas@theweeklychallenger.com

Related Article | African American moments in rock and roll history, part 2

A bouncy tune about a man in his V8 Ford speeding after his unfaithful girlfriend in her Cadillac Coupe DeVille, Chuck Berry’s first hit “Maybelline” was the key in the ignition for rock and roll. With its chugging rhythm, relentless guitar and clever lyrics that offer the excitement of a chase, it was gleefully embraced by the country’s young generation. More…