Black people were only allowed in downtown St. Petersburg except to go to work. Dr. Ralph Wimbish integrated the downtown Mass Brothers lunch counter in 1961.

BY DEIRDRE O’LEARY, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Based on the Florida Holocaust Museum’s 2015 exhibit of the same name, the museum presented a virtual overview of the Benches, Beaches & Boycotts—the Civil Rights Movement in Tampa Bay exhibit on Feb. 10 in conjunction with St. Petersburg College for Black History month.

Erin Blankenship, deputy director of Florida Holocaust Museum, led the presentation, focusing on the African-American communities of Central Avenue in Tampa, Newtown in Sarasota and neighborhoods in St. Pete, including the Deuces.

Sarasota’s Black business district was formerly in the district of Overtown; however, whites complained they had to go through Overtown to get to downtown Sarasota so it was moved to Newtown.

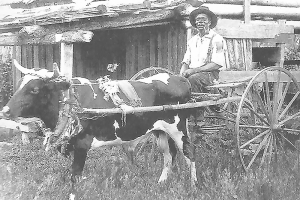

John Donaldson was the first Black man to settle in St. Pete after the Civil War. He was an employee of Louis Bell Jr. In 1888, more Black people came to work for the railroad and settled in Peppertown.

Soon after the Methodist Town and Gas Plant neighborhoods were established. All were Black neighborhoods and African Americans were prohibited from living elsewhere. Living with the legacy of segregation, St. Pete continues to be one of the most segregated cities in the country, according to Blankenship.

Churches were, then as now, important community centers in the different areas of Tampa Bay. Prominently featured were St. Paul’s AME in Tampa, Bethel AME Church in St Petersburg and Payne Chapel AME in Sarasota.

The Chitlin’ Circuit was a group of nightclubs, restaurants and halls that allowed African Americans to perform. In St. Pete, the Jordan Dance Hall, now called the Manhattan Casino on 22nd Street South, was built in 1925. James Brown may have had his start there. In 1961, Ray Charles performed in Campbell Park, and Hank Ballard wrote the popular song “The Twist” after performing one night in Tampa and seeing people wildly twisting their bodies to the music.

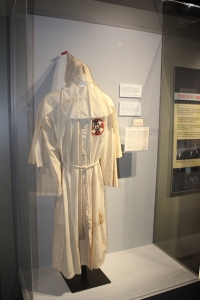

The Ku Klux Klan originated in Tennessee during the Reconstruction era and by 1925 had 3 million members. Jim Code, a staff member of the local Chamber of Commerce, helped to organize the St. Pete’s KKK chapter. This was commonplace in communities as local leaders were KKK members and organizers.

In 1937, more than 200 Klansmen marched through the black neighborhoods of St. Pete to discourage its citizens from voting in the police chief election and during the same year, kidnapped and “tar and feathered” union organizer Joseph Shoemaker of Tampa.

In 1937, over 200 Klansmen marched in Black neighborhoods to intimidate people from voting in the police chief election. That same year, they kidnapped and murdered union organizer Joseph Shoemaker of Tampa.

Spa Beach in St. Pete, Lido Beach in Sarasota and Ben T. Davis Beach in Tampa were whites-only despite being open to the public. In 1955, a group of civil rights activists with the Civil Coordinating Committee attempted to go to Spa Beach. They were not allowed and directed to South Mole Beach, now Demens Landing, where Blacks were allowed.

A lawsuit was filed by Dr. Fred Alsup and others against the city. Even though they won, city workers would close the pool when Blacks tried to swim. In 1959, the pool and beach at Spa Beach were finally integrated.

In Sarasota, on Oct. 3, 1955, a group of 100 African Americans went to Lido Beach and waded into the water. The NAACP made it their mission to integrate the beaches there.

They gathered a convoy after church on a Sunday and everyone went into the water for a “wade in” in their good Sunday clothes. They endured bricks thrown at them, epithets and more. After several more wade in actions, it still took more than two years to integrate the beaches.

Mayor Julian Lane in Tampa created the first bi-racial committee in the area in order to address integration issues.

One of the area’s first lunch counter sit-ins was on Feb. 29, 1960, in Tampa. The bi-racial commission became involved to avoid national media coverage according to Blankenship. The local newspapers were notified in advance and police provided security for the activists. As a result there was no violence and no national coverage.

In March 1960, downtown St. Petersburg stores, including William Henry, Maas Brothers and Kress had sit-ins. Rather than serve the African Americans, they closed the stores. Picket lines resulted and a Christmas boycott was put in place. The boycotts led to a loss of revenue for Webb City who in turn sued the NAACP in an attempt to recover.

In 1966, Joe Waller, now known as Omali Yeshitela, became frustrated after writing letters and protesting with others yielded no results and ripped down a racists mural in City Hall. He served prison time and drew attention to the civil rights struggle. The wall remains blank today.

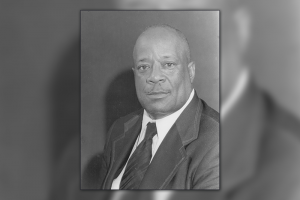

Twelve Black police officers, now known as the Courageous 12, along with attorney James Sanderlin, file a lawsuit against the City of St. Petersburg in 1965 charging racial discrimination.

The case was thrown out but was won on appeal in 1968. In 1969, the 12 officers were assigned to white areas. This resulted in changes to police departments throughout the south.

It wasn’t until 1972 that schools were integrated in Tampa Bay, though the Supreme Court’s Brown vs. Board of Education decision was held in 1954. Robert Saunders, Jr., the son of Tampa NAACP president Robert Saunders Sr., was the first Black student to integrate a Tampa schools.

In Sarasota, young children often had to ride buses for 45 minutes to get to school following the closing of neighborhood Black schools. Students boycotted the schools and the loss of revenue resulted in schools reopening.

In June 1967 a black man was shot by a Tampa police officer. Riots broke out for three days in the Central Avenue business district. Local, state and federal officers came to the scene. More than seven buildings were completely destroyed.

On May 6, 1968, St. Petersburg sanitation workers called a strike for better wages. They were joined by 150 workers; all were fired and replaced. As a result, the mostly Black sanitation department became nearly all white. This led to a three-month-long standoff led by Joseph Savage of the Sanitation Department and attorney Sanderlin.

National civil rights and labor leaders came to help but city officials refused to negotiate. A group of business leaders negotiated a settlement and the strike ended in Sept. 1968.

The exhibit and presentation is not a comprehensive history of the local struggle for civil rights; it is meant to capture the important period of the 1960s and 1970s.

St. Petersburg: The African American Heritage Trail

Sarasota: Newtown Alive

Tampa Bay History Center Walking Tours

Florida Holocaust Museum: Beaches, Benches and Boycotts Online