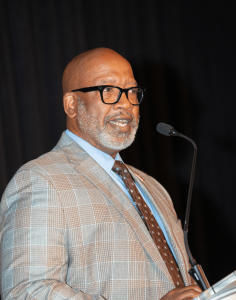

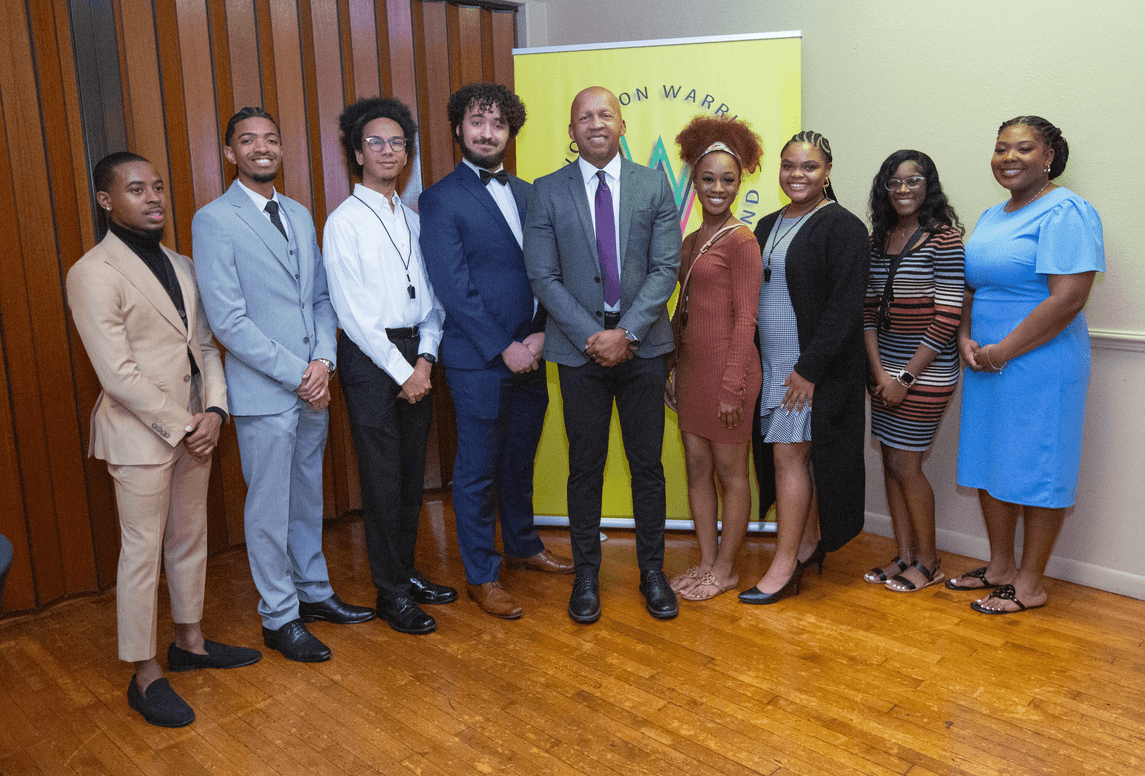

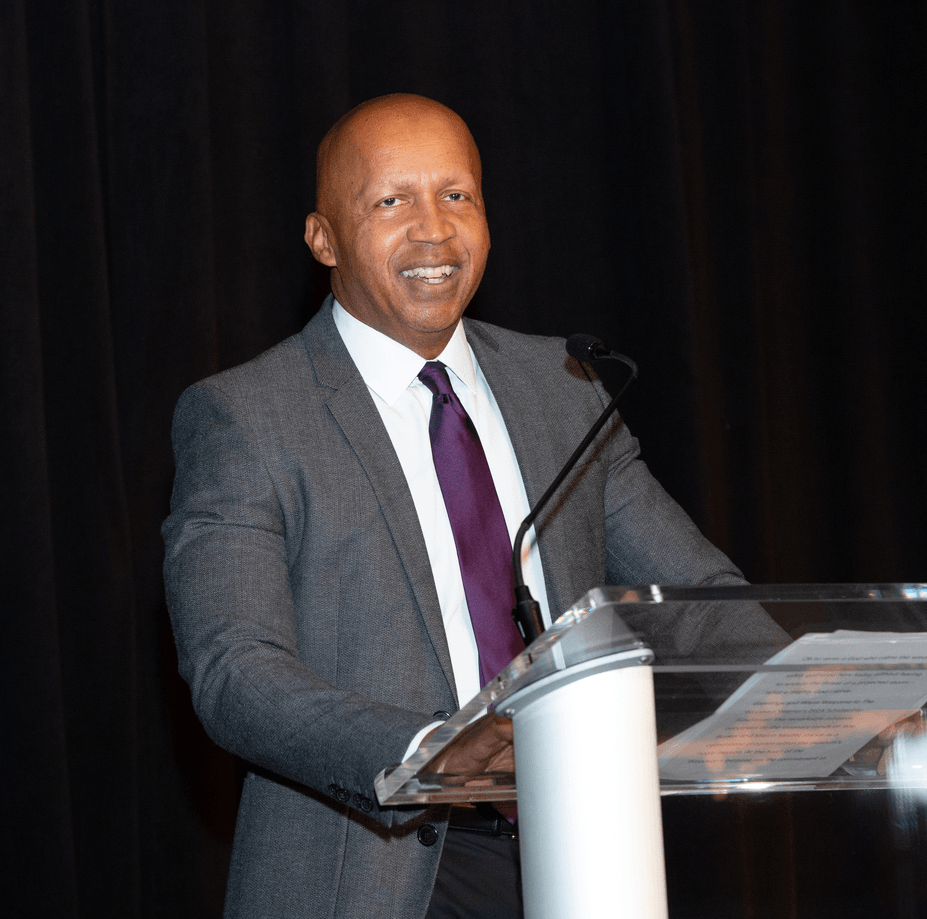

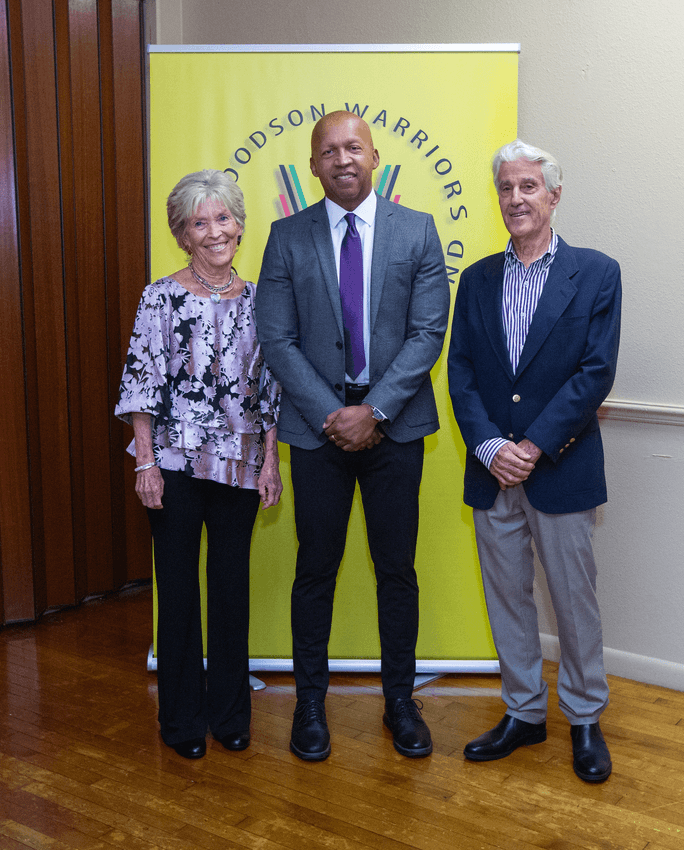

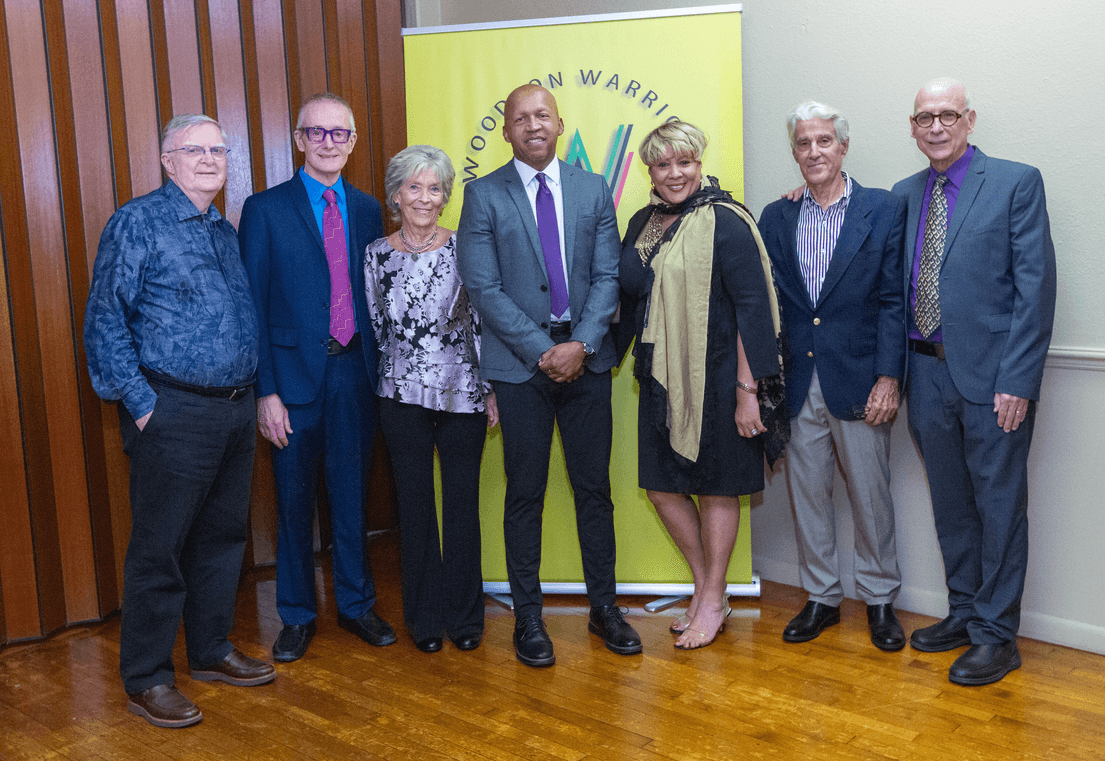

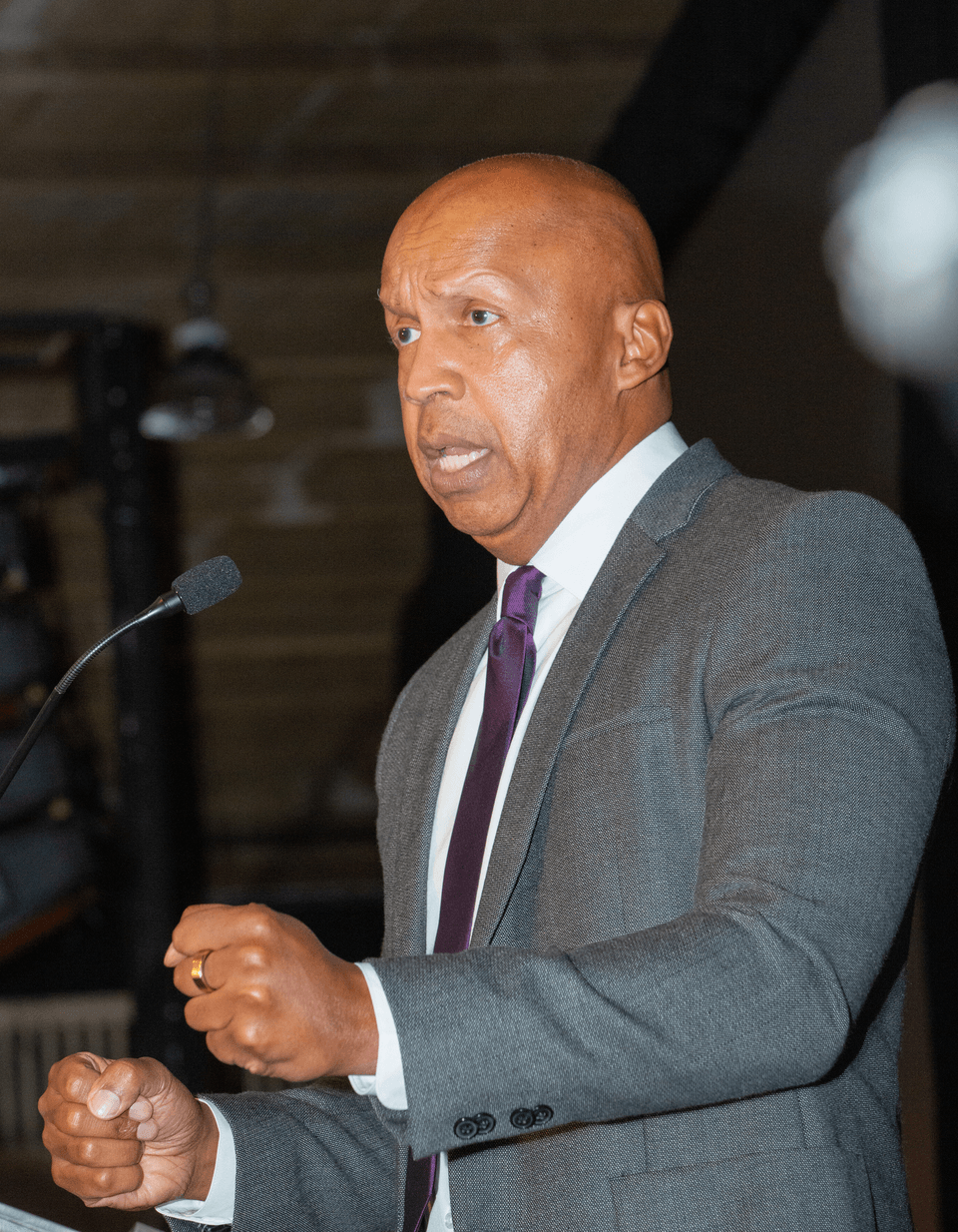

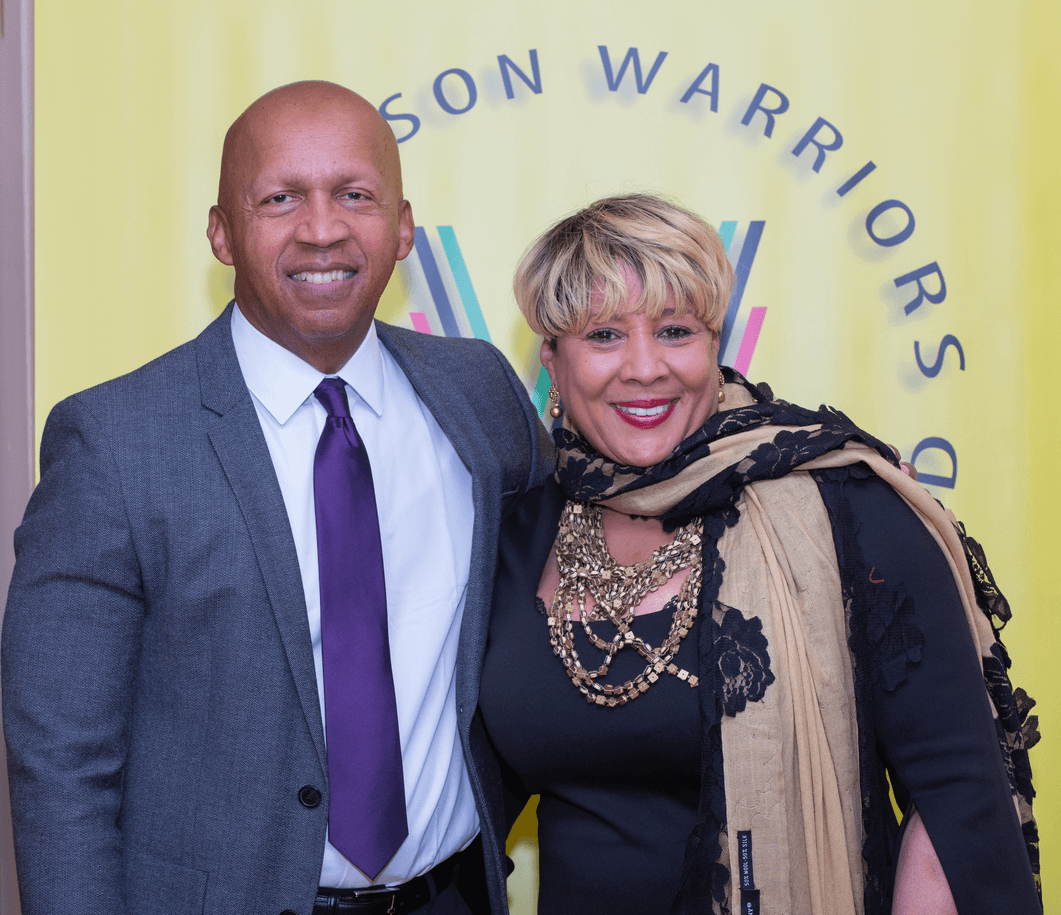

Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, headlined The Woodson Warriors fundraising event on Sunday, Feb. 4, at the historic Coliseum.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

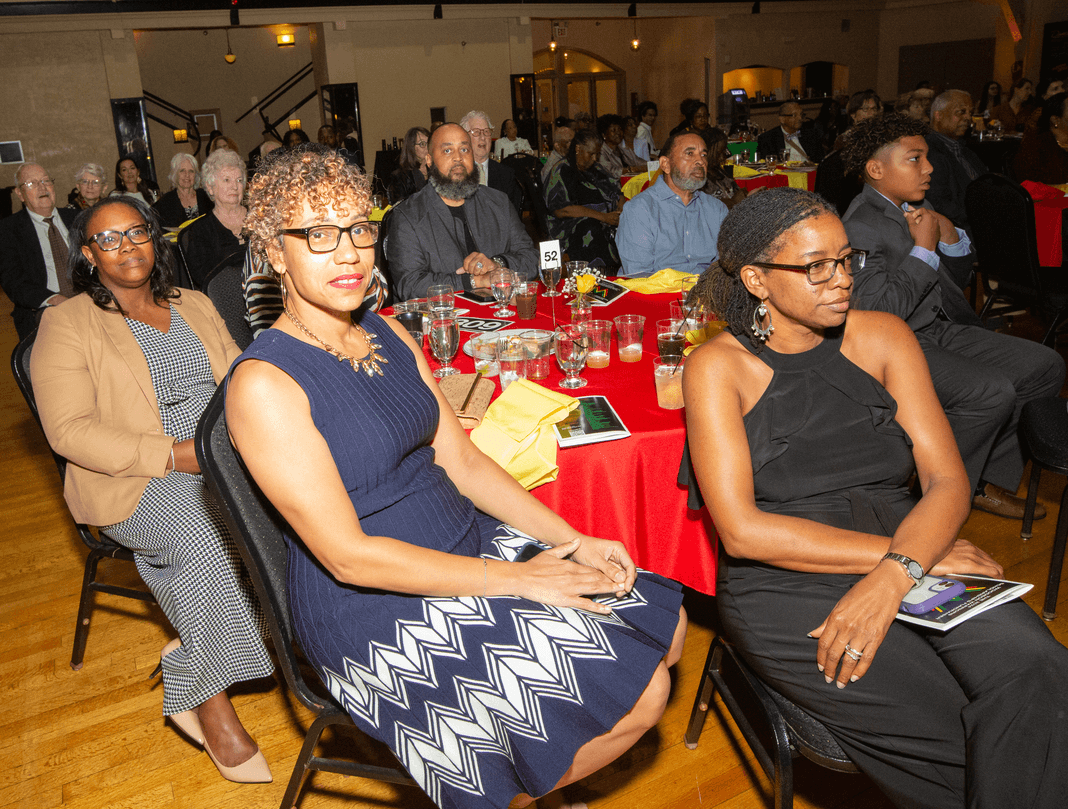

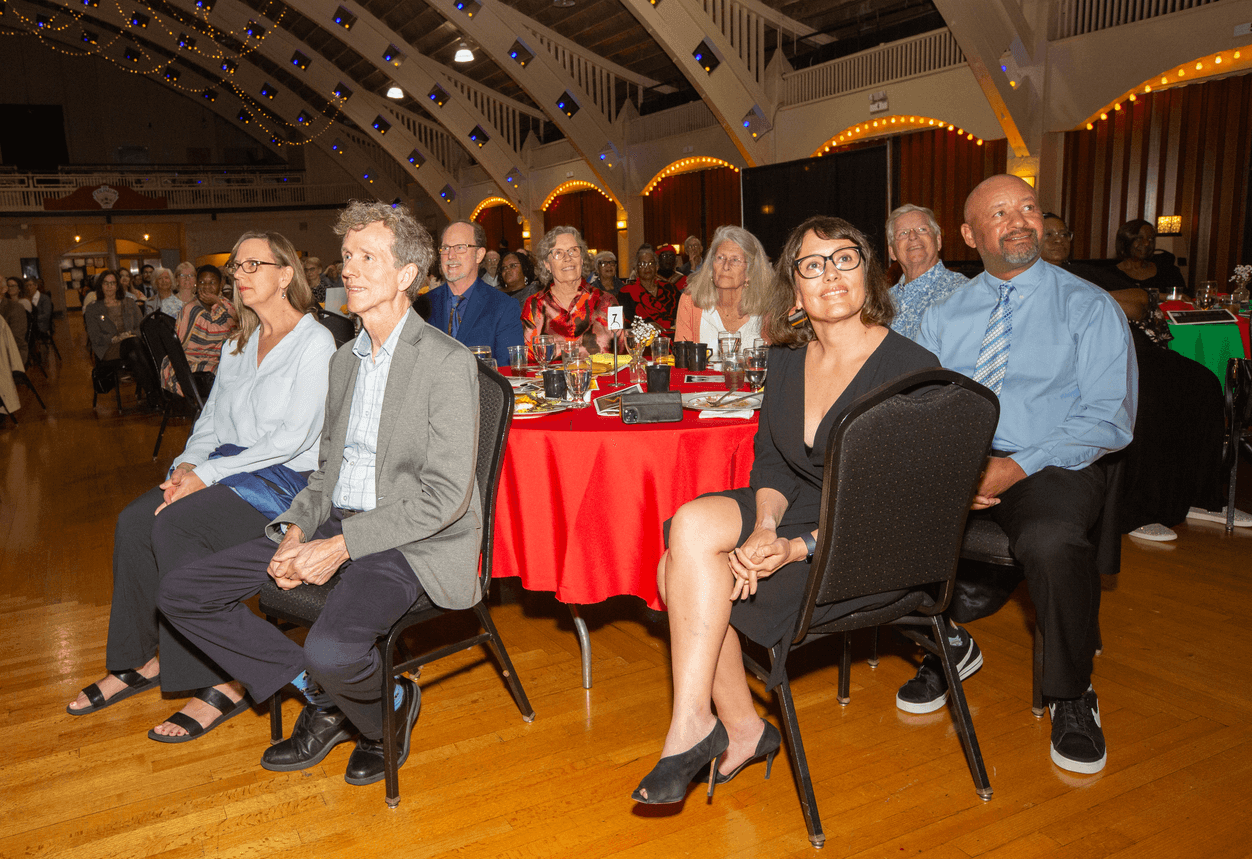

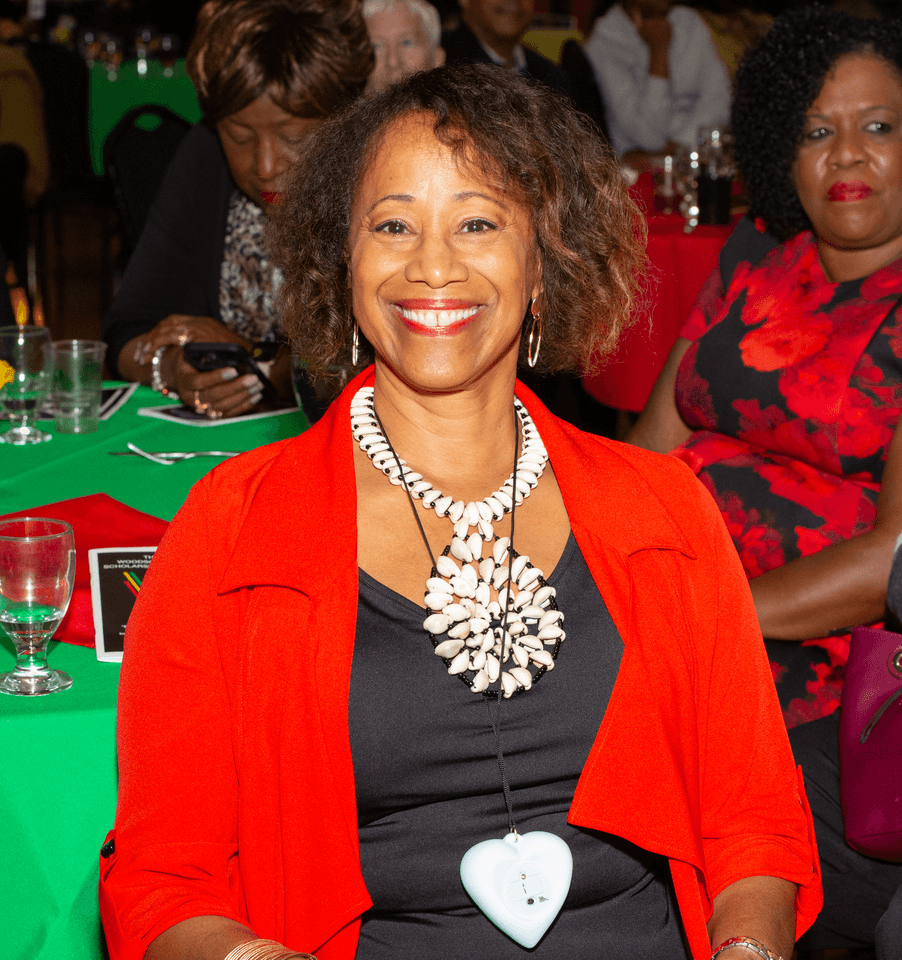

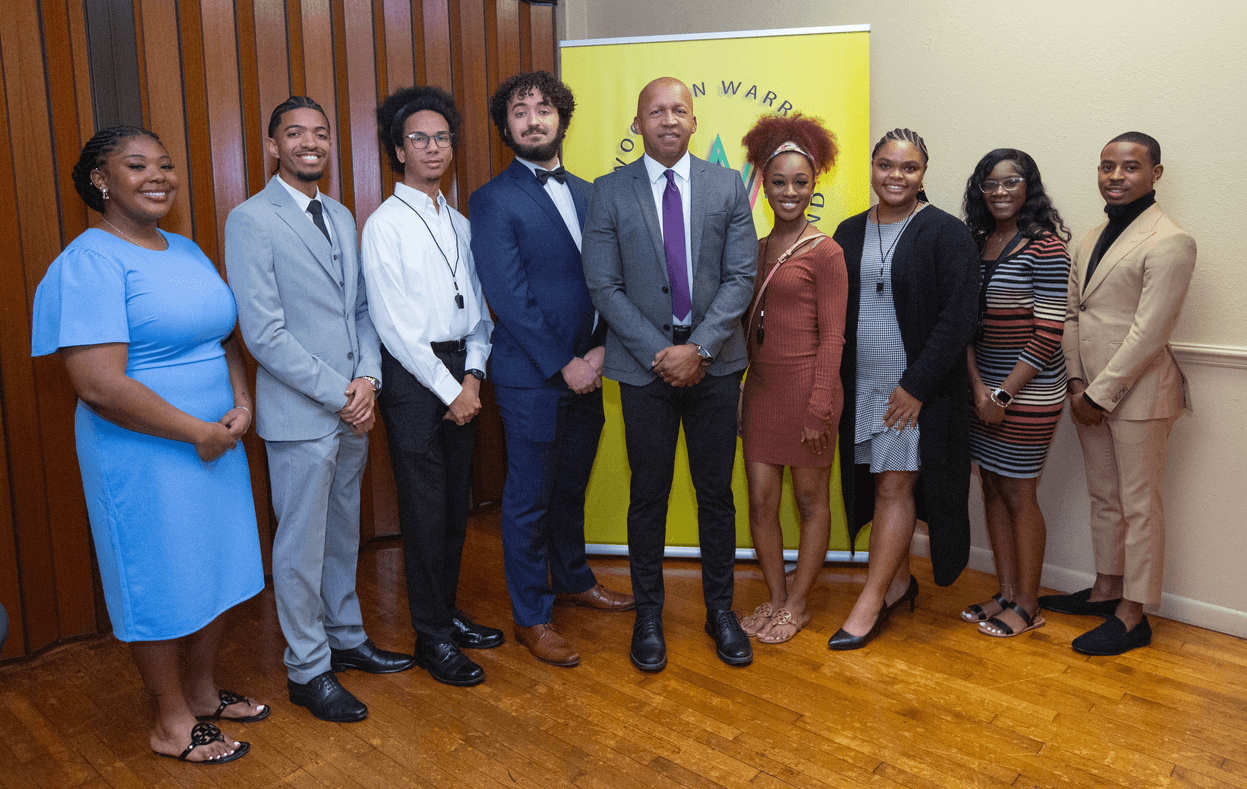

ST. PETERSBURG — The Woodson African American Museum of Florida’s prestigious scholarship fundraiser — The Woodson Warriors — is a testament to its commitment to supporting deserving Black high school graduates and college scholars.

Held at the historic Coliseum on Sunday, Feb. 4, the fundraiser is more than a financial endeavor; it’s a journey toward bright futures. The Woodson aims to empower 50 scholars with each dollar raised, acknowledging their exceptional academic achievement and impactful community service. This year’s fundraiser yielded more than $300,000.

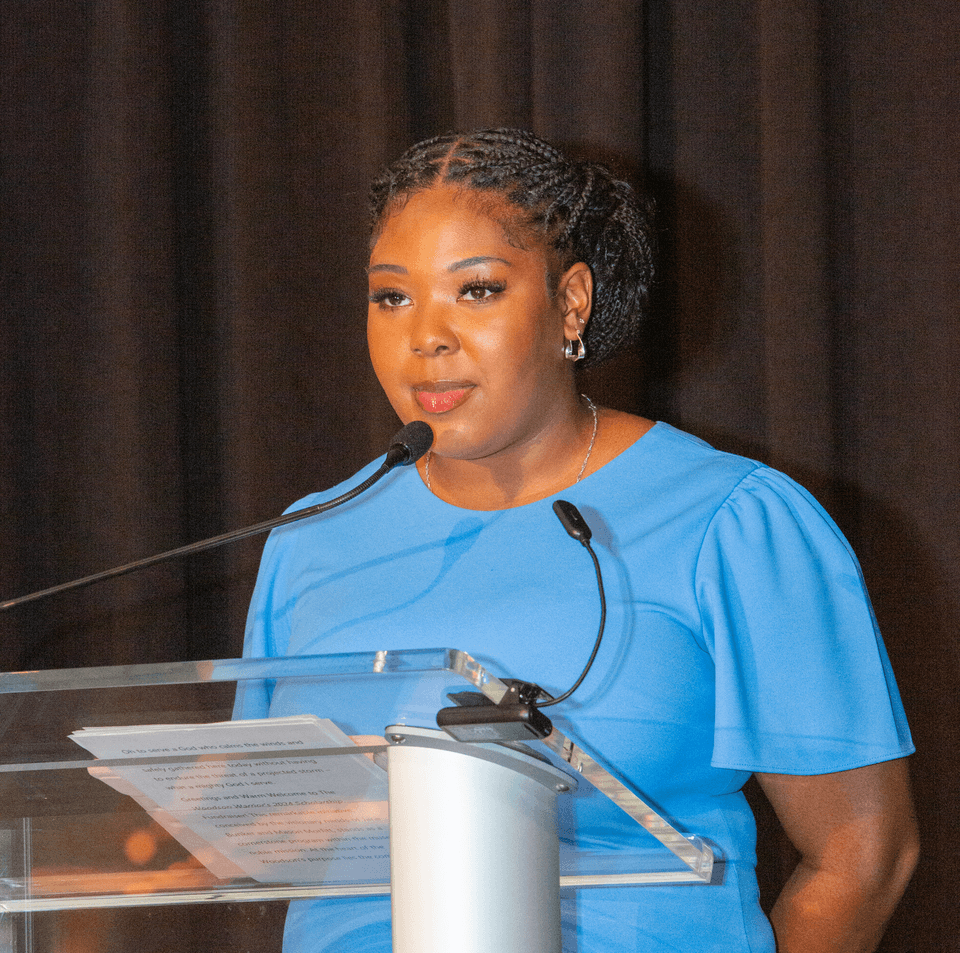

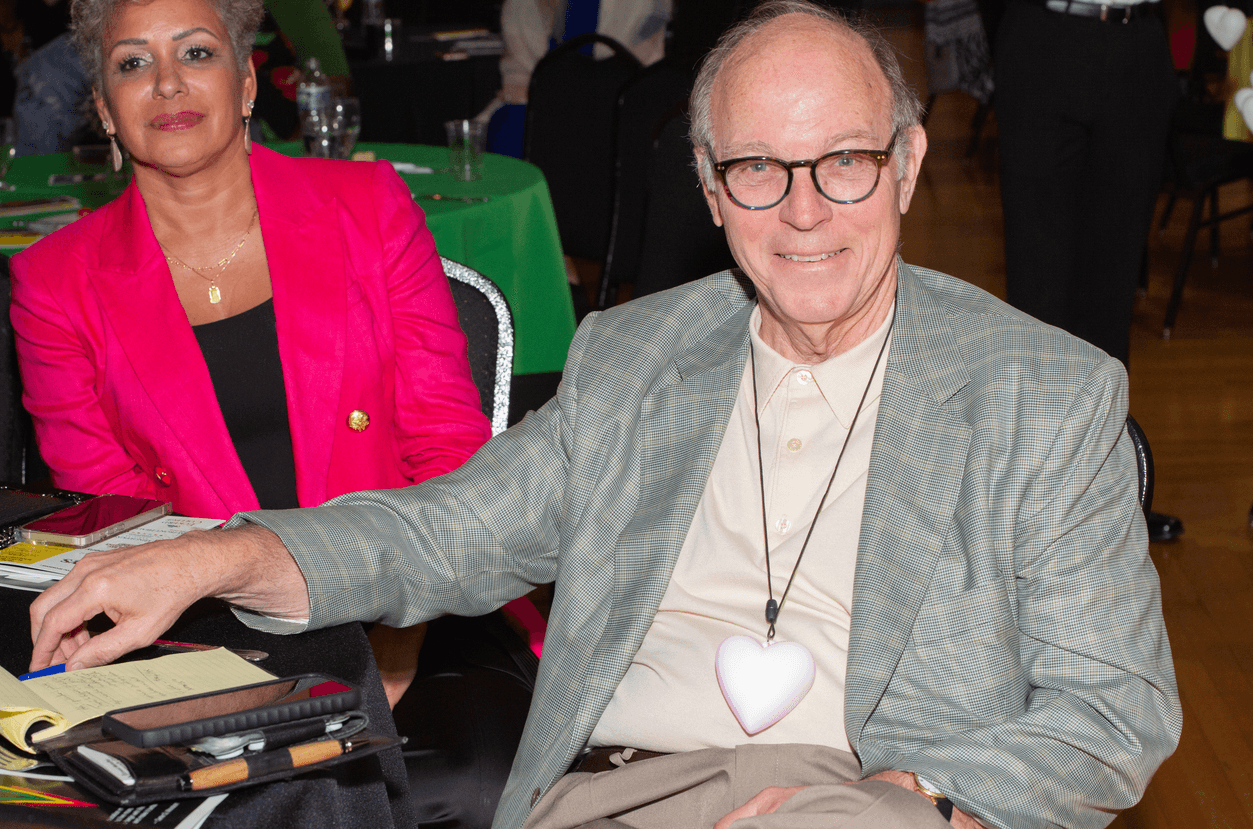

Terri Lipsey Scott, executive director of the Woodson African American Museum of Florida, explained that the scholarship fund’s success is owed to nationally recognized artist Jane Bunker, who got the ball rolling, and husband and wife duo Jeanne and Kevin Milkey of the Milkey Family Foundation, who pledged $50,000 annually for the next 10 years.

Mayor Ken Welch said young people are our best investment, and will shape the destiny of our city, nation and world, adding that the Woodson Warrior Scholarship plays a pivotal role in fostering the potential of our students.

“Today, as we come together to celebrate the achievements of our students, let’s reflect on the collective strength and potential that we can achieve in St. Pete through the power of education,” Welch said. “We are a community that believes in the power of opportunity, the promise of our youth and the importance of our true history.”

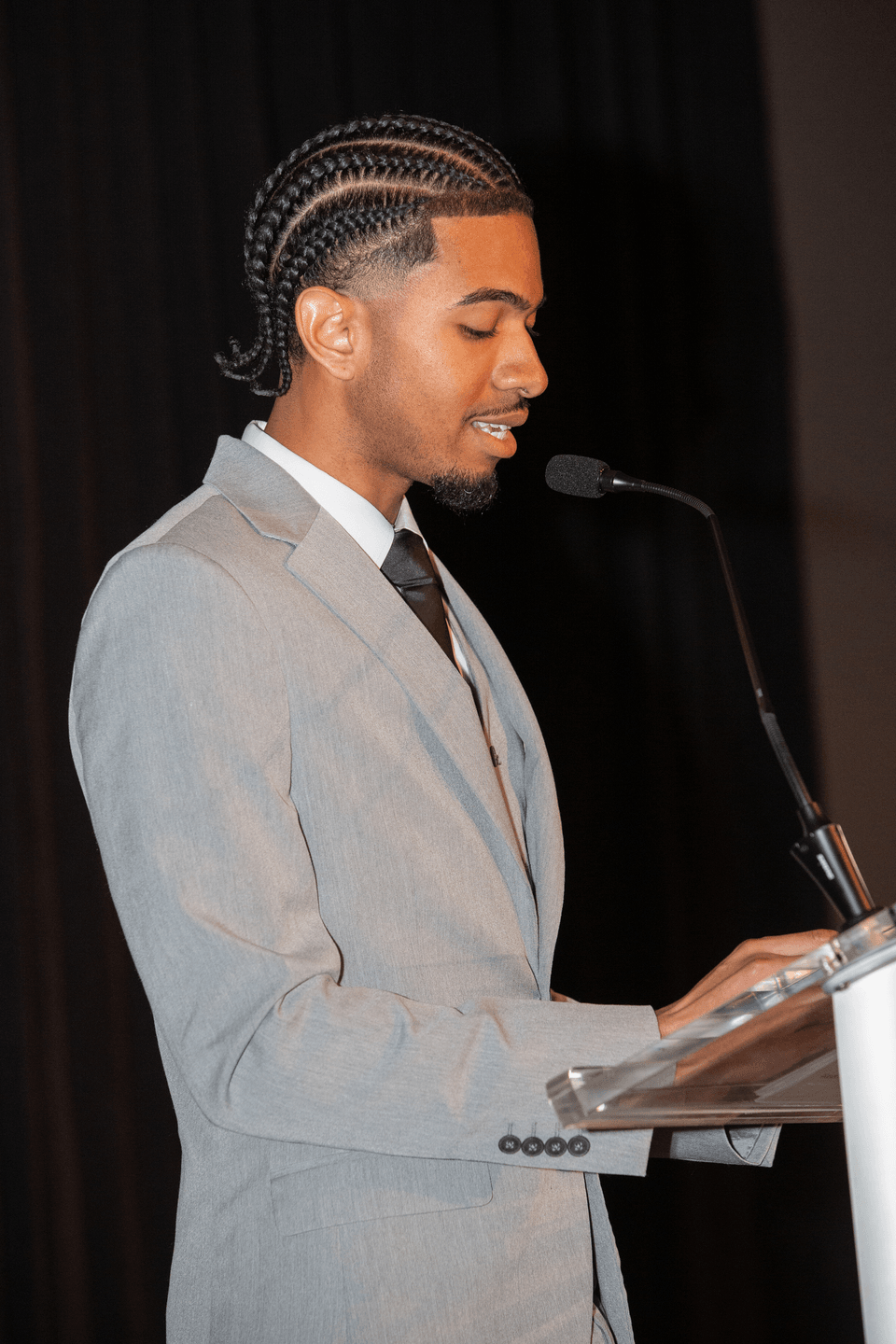

Woodson Warrior Chandrahassa Srinivasa introduced keynote speaker Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization in Montgomery, Ala.

Stevenson, who has argued and won several cases before the U.S. Supreme Court, said that one of the greatest joys of his career was winning a case that banned mandatory life sentences for children. Those children were told they would die in prison, and they reclaimed their lives, Stevenson said, acknowledging one such beneficiary in the audience, a Florida teen who was “unjustly told that he was beyond redemption, beyond hope” and was condemned to die in prison.

“We were ultimately able to win a reversal of that sentence,” Stevenson said. “For the last decade or so, he’s been in the community, contributing, helping other young people, modeling something powerful and beautiful for all of us to recognize.”

Each Woodson Warrior Scholarship recipient is eligible for up to $20,000 over their four-year college career, $5,000 per year, depending on their GPA, with a minimum of $2,500 per year.

The United States has the highest incarceration rate in the world, he disclosed, and 80 million people have criminal arrest records, which can hinder them in securing employment or loans. The percentage of women going to prison has increased 800 percent in the last 25 years, and 80 percent of them are single parents with minor children, which means another generation is affected. One in three Black male babies born in this country is expected to go to jail or prison in his lifetime.

Stevenson said that as the grim numbers have increased in the 21st century, people have met them largely with indifference. In talking to teens in various communities, he related that many 13 and 14-year-olds have admitted to him that they fully expect to be in prison by the time they reach 21, underscoring a hopelessness that is shaping the lives of too many young people.

He said there are things that we can do to create a healthier world, and identity is critical.

“A lot of people think that we can’t achieve the kind of progress, the kind of health, the kind of togetherness that this community needs,” Stevenson said. “We’ve got to have an identity to say to our friends, to say to those who doubt that we can do these things. Identity is going to be key to what allows us to sustain and to overcome the challenges that we are facing at this time.”

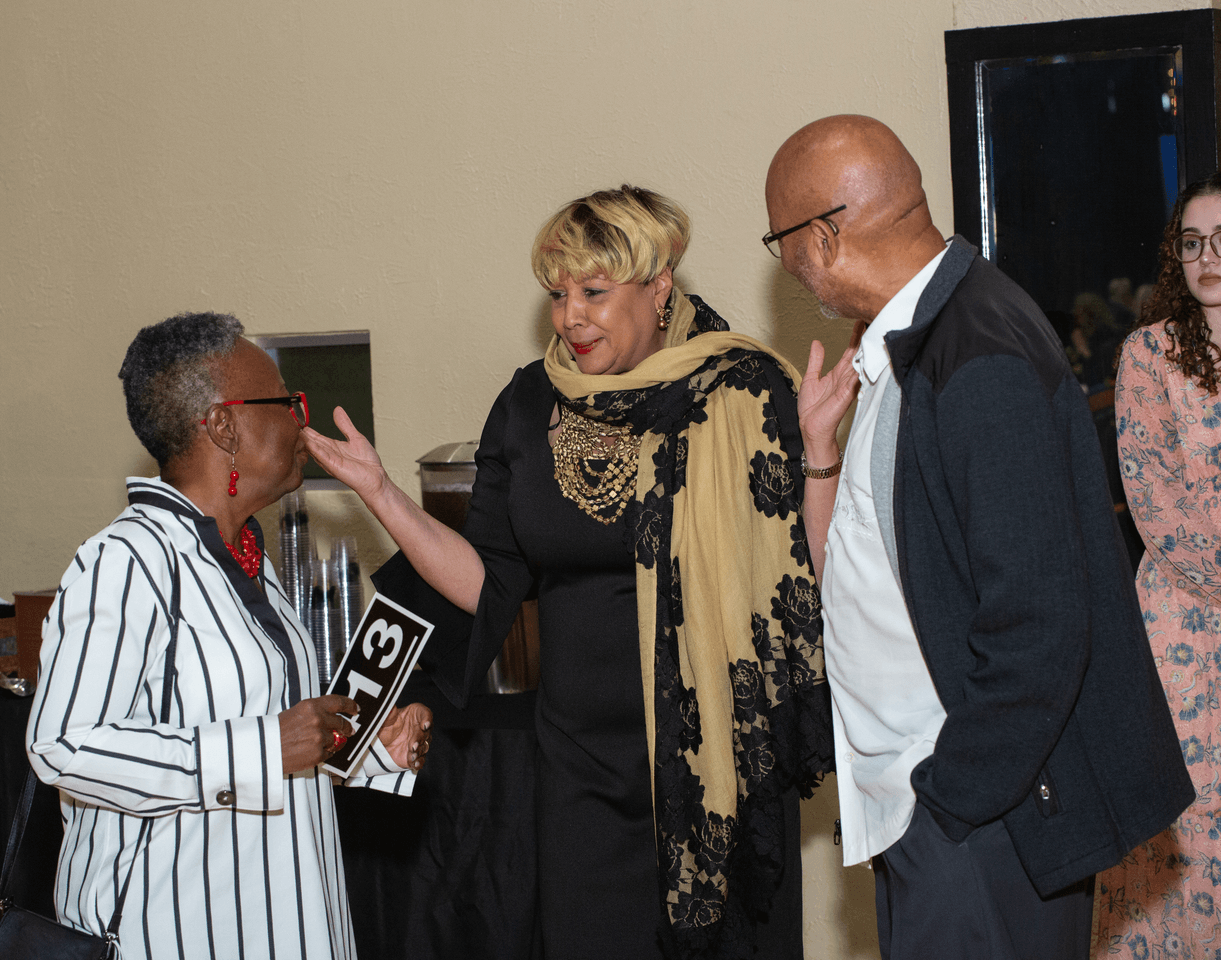

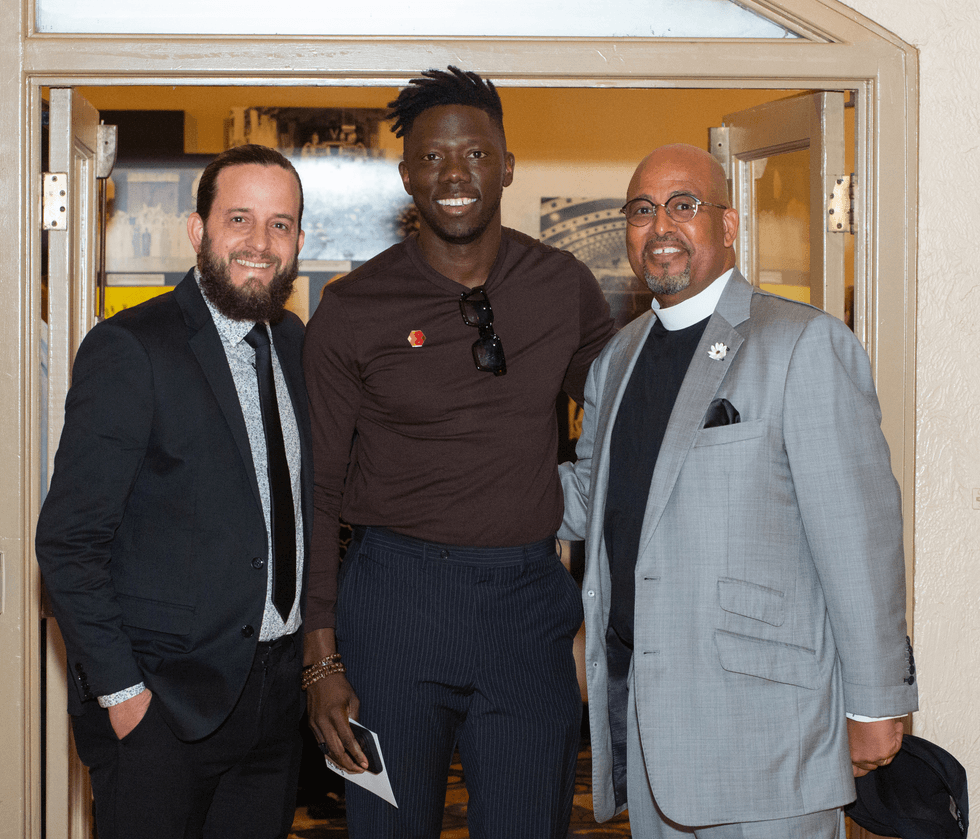

Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg’s Joshua Bean and Marcus Brooks with Rev. Kenny Irby, Historic Bethel AME Church

We need to get closer to those who are suffering, he said, as it is too easy in this country to isolate ourselves from people who are marginalized, disfavored, incarcerated, and condemned.

“We have the ability in this country to create these separate spaces, and sometimes that separation feeds the kind of inequality and injustice that too often persists,” asserted Stevenson.

Elected officials too often create policies that are not effective because they’re created in places that are different from where these problems are actually occurring, he explained.

“You can’t say you want to end injustice if you’re not close to people who are suffering injustice,” he said.

While attending Harvard Law School, Stevenson met with an inmate on death row in Jackson, Ga. A nervous young law student at a maximum-security prison, he was taken aback at how “burdened down” with chains the inmate was when he came face to face with him. It took the guard 10 minutes to unshackle him.

Stevenson had been sent to inform the inmate that he was not at risk of execution any time in the next year, and he told the inmate that directly. The inmate asked to hear it again. Stevenson repeated himself. Again, the inmate implored him to repeat it, and Stevenson obliged.

“When I said it the third time, this man grabbed me, and he hugged me, and he said, ‘Thank you, thank you, thank you!'” Stevenson said.

The inmate hesitated to believe other prison officials or guards but trusted Stevenson. He had avoided having his wife and children come to visit for fear of a pending execution date, yet after Stevenson spoke to him, he knew he could see his family.

“I couldn’t believe, even in my ignorance, just being proximate could have an impact on the quality of someone’s life,” Stevenson said.

He explained that you don’t have to have a strategy or solution; you just have to be present to understand other people’s suffering and even have an impact, and the things you see and hear will inform your decision-making moving forward.

Stevenson wound up talking to the inmate for three hours, well over the allotted time, and the guards took out their annoyance on the inmate by handling him roughly and, after wrapping him in chains again, shoving him back toward his cell. But as the inmate reached the doorway, Stevenson recalled, he planted his feet, turned his head, and told Stevenson, “Don’t worry about this; you just come back.” Then he closed his eyes and started to belt out the hymn “Higher Ground,” singing, “I’m pressing on the upward way. New heights I’m gaining every day…”

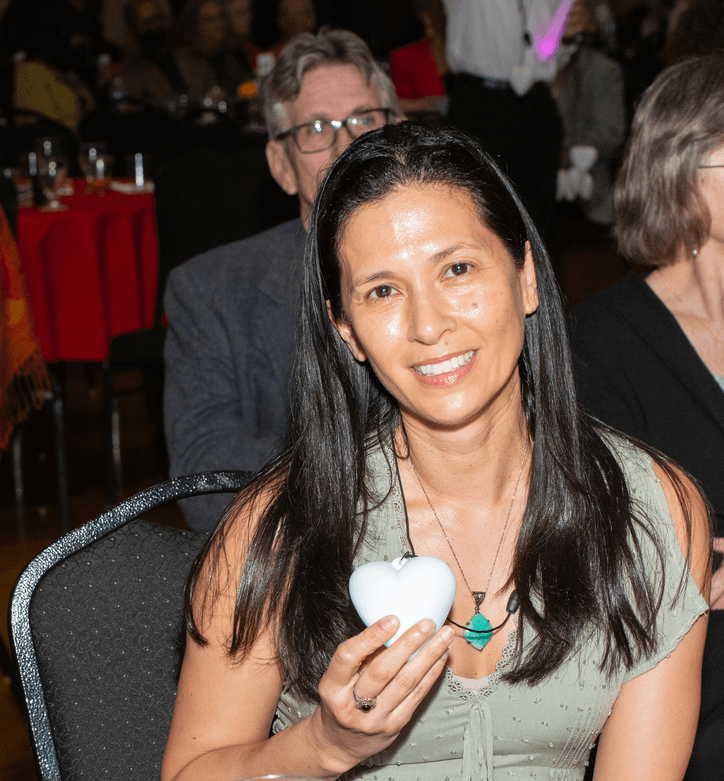

Bryan Stevenson, founder and executive director of the Equal Justice Initiative, and Terri Lipsey Scott, executive director of the Woodson African American Museum of Florida

“When I heard that man sing, everything changed for me,” Stevenson said. “That was the moment I knew I was being called to help condemned people get to higher ground. I knew that if they don’t get to a higher ground, I can’t get to a higher ground.”

There are poor communities in this city and across the state where people are singing, he said, and “we’ve got to hear those songs to understand what it means to increase the justice quotient in our state.”

Identity and proximity are crucial, he said, but we must also change the narratives that are floating in our country right now, ones that foster bigotry, hatred and violence, Stevenson warned.

“We cannot allow ourselves to be corrupted by these narratives that are rooted in what I call the politics of fear and anger,” he said.

Stevenson pointed to the now-debunked criminological theory of “super predators,” which maintained a growing number of children, usually from urban areas, were capable of and willing to commit violent crimes. Since the term “super predator” surfaced in the 1990s, some states — Florida being one of them — began lowering the age at which a child could be tried as an adult. Consequently, thousands of children went to prison, creating a robust school-to-jailhouse pipeline.

“We’re talking about zero tolerance, and the next thing you knew, five and six-year-old children were being placed in handcuffs in schools for behaviors that most of us engaged in,” Stevenson stated. “That narrative was so destructive, and we didn’t respond the way we needed to respond, and I still see the consequences of that narrative!”

We do not show our commitment to children by looking at how well we treat talented, gifted, and privileged kids; Stevenson said that our commitment to children has to be expressed by how we treat poor kids. This narrative must change.

“I think we need to change the narrative about race in America because I don’t think we’re free,” he said. “I think we are still burdened by our history of racial inequality. It doesn’t matter where you live. You can live in the South, you can live in the West, you can live in the Northeast, you can live in the Midwest. No matter where you live, if you live in the United States, you are living in a space where there is this long history of racial inequality — racial injustice. That history has created these toxins in the air, just like pollution, and it doesn’t matter how hard you try; when you breathe this environment, you get unhealthy.”

We have responded to this problem with silence and refused to talk about the manifestation of this history and its threat, Stevenson said, and that silence has meant that each generation has been burdened with this problem. By ending the silence, we can change the narrative.

Even to justify the great evil of slavery, whites came up with the narrative that Black people are less capable, less worthy, less deserving, less evolved and even less human than white people, he said. That narrative of racial difference gave rise to an ideology of white supremacy and racial hierarchy.

“That narrative was the true evil of this legacy of slavery,” he said.

It persisted for decades, even as African Americans fled the terror of the South to settle in cities like Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, Kansas City, Oakland, Los Angeles and many others, only to find the ubiquitousness of this same narrative — that “presumption of dangerousness and guilt that gets assigned to Black and Brown people,” he said.

It persists, even to this day. Stevenson recalled representing a young person in the Midwest. As he arrived in court early, he sat at the defense counsel’s table, where the judge, upon seeing him seated there, angrily told him to get back out to the hallway as he didn’t want defendants sitting in court without their lawyers.

Stevenson then informed the judge that he was not the defendant but the attorney. The judge responded by laughing out loud. The prosecutor started laughing as well. Stevenson recalled sitting there holding the table and forcing himself to laugh, too, because he didn’t want to disadvantage his client, who was more vulnerable than Stevenson.

“Afterward, I remember sitting in my car thinking, ‘Wow, here I am, this middle-aged Black man with all of these degrees and all of these awards, in my best suit … and I’m still required to laugh at my own humiliation!'” he said.

We need an era of truth, reconciliation and justice in this country to replace the old narrative, Stevenson said, fully acknowledging the past is an integral part of that.

“When we acknowledge the wrongs, when we acknowledge the harms, that’s when our hearts open up, and that’s when grace and mercy can do all these transformative things,” he said. “It’s going to take courage to do this.”

He stressed that this is not the time to step back from this necessary calling to change the narrative, adding that hopelessness is the “enemy of justice,” and we must be hopeful about what we can do.

Each Woodson Warrior Scholarship recipient is eligible for up to $20,000 over their four-year college career, $5,000 per year, depending on their GPA, with a minimum of $2,500 per year.