Freddie Crawford and 11 black police officers sued the City of St. Petersburg for workplace equality and won in 1968. He died last Friday and will be laid to rest June 1.

BY ROGER CLENDENING, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Freddie Lee Crawford, a former law enforcement professional who fought the City of St. Petersburg for equality in the workplace, died last Friday, May 17 at Palms of Pasadena Hospital with his family by his side. He was 81.

“The passing of our father is a tremendous loss to our family, our community, and to the world,” said daughter Peggy Crawford in a statement released by the family. “Our father was a compassionate man who had the ability to calm any situation.

She went on to say that Crawford was always ready to lend a helping hand to those in need and that it is their “hopes and prayers that others will gain the courage to stand for what’s right without any compromises, and to support the younger generations to their full potential.”

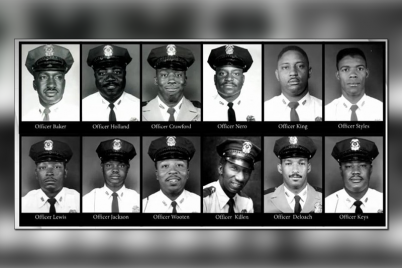

In 1965, Crawford, along with black officers Adam Baker, Raymond DeLoach, Charles Holland, Leon Jackson, Robert Keys, Primus Killen, James King, Johnnie B. Lewis, Horace Nero, Jerry Styles and Nathaniel Wooten filed a landmark lawsuit against the city for discrimination on the force.

Jackson, 78, is the last surviving member of the Courageous 12, the name given to the 12 black police officers who sued to desegregate the St. Petersburg Police Department.

“It’s a deep hurt, his passing,” Jackson declared earlier this week during an interview at his home. “He was our leader, the one who came up with the idea to sue the city and fully integrate.”

Jackson, with a wistful smile, recalled that Crawford, as a leader, and King, recruited him in 1963 to become a police officer.

Jackson said he and others admired Crawford’s tenacity and fortitude in fighting workplace environment barriers in a department dominated administratively and militarily by white men.

“Freddie kept pulling down the ‘whites only’ signs at the water fountain in the cop shop,” Jackson recalled. “Each time the white guys would put the sign back up, Freddie would snatch it down, reminding us that we would be treated equally, or else.”

Jackson said Crawford was a “one of a kind true leader” who led by example.

Given that affirmation, consider the perspective on Crawford offered by Goliath J. Davis III, St. Petersburg’s first black police chief:

“Those of us from Methodist Town are fond of saying it is easy to discern individuals who really know us from acquaintances. The key is what they call you. Acquaintances typically know you by your given name. The Methodist Town Family may or may not know your given name but universally know your nickname,” he explained, revealing Crawford’s moniker. “I have known Ne Ne all of my life.”

For Davis, Crawford “is family, mentor, friend and my community police officer.”

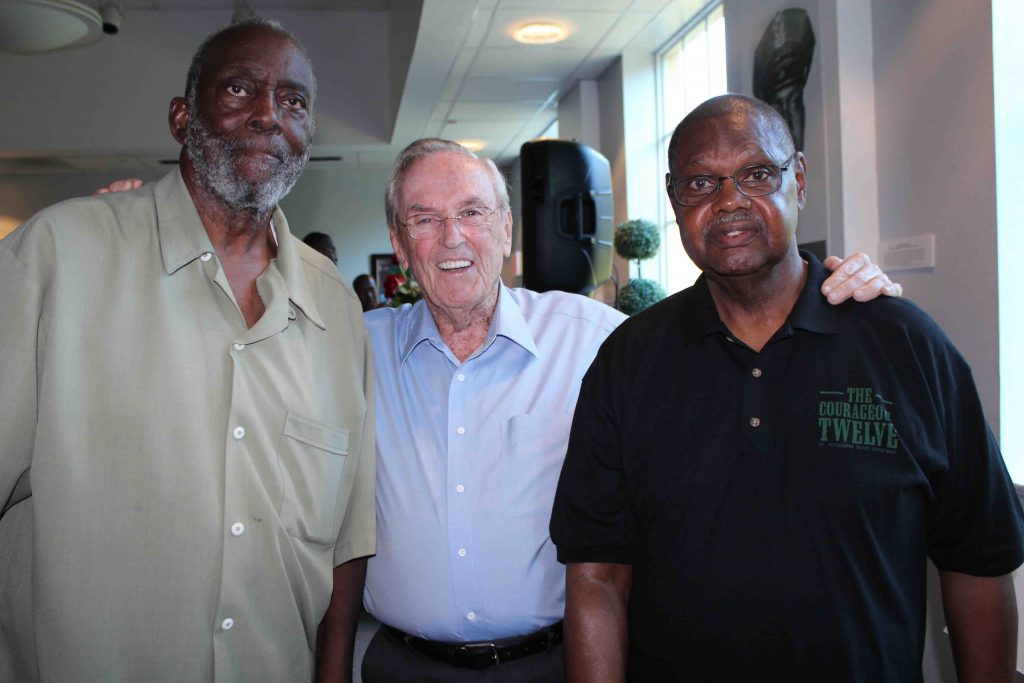

L-R, Freddie Crawford, former Mayor Don Jones and Leon Jackson at a Courageous 12 tribute held at the Carter G. Woodson African American Museum in 2015.

He reflected on how Crawford and the 11 other officers who sued the city are inextricably tied.

“They represent the epitome of community policing. Their commitment to fairness and equality changed the lives of the people they policed as well as the lives of African-American police officers involved in the enterprise nationwide,” he said.

Davis said as a police officer, Crawford was stern when necessary, but his general demeanor was one of humility, patience, fairness and compassion.

“He was a visionary and a dreamer. He dreamed of economic prosperity and equality for his people and our communities and formed several businesses (including Plow Boy Restaurant and Zenith Security) to provide job opportunities and enforcement experiences for African-American men and women,” Davis asserted.

In the early 1960s, Crawford and his fellow black police officers serving on the St. Petersburg police force were only permitted to police black neighborhoods. The segregation of authority went so far as to mark patrol cars with a “C” for “colored” to designate that a black officer was inside.

Of the 15 black policemen in the department, Crawford and 11 other uniformed officers had been holding meetings amongst themselves in their homes and had planned to take their complaints to the chief. The other three officers had refused, stating they wanted no part of it.

The officers approached then-Chief Harold Smith with the complaint that they were only allowed to patrol the black neighborhoods and felt that they should be allowed to police the whole city. The group of 12 officers also complained that promotion was nonexistent for them. Where white officers were promoted regularly, but black officers could not even take the sergeant’s exam.

Smith told the officers that the reason they were always assigned to the same area was that the department believed they could handle the black neighborhood better than the white officers. But white officers were allowed to patrol 22nd Street South. These white officers didn’t walk the beat but patrolled the area from their cruisers.

They met with Smith two separate times, and each time the chief told them that he’d get back with them. After getting no results, the group asked for a third meeting. Smith refused to meet with them anymore.

The 12 continued to have meetings amongst themselves, and Crawford came up with the idea to sue the police department. Baker suggested James B. Sanderlin as a good civil rights attorney.

Freddie Crawford and the late Adam Baker at a Courageous 12 tribute held at Faith Memorial Baptist Church in 2012.

So Crawford and Baker met with Sanderlin at a drug store and told him they had all voted to file a lawsuit against the police department for discrimination and wanted to know if he’d be their lawyer.

On May 11, 1965, the lawsuit was officially filed at the federal court in Tampa. A group of black officers taking on the department did not sit well with some of the other white policemen.

“They were upset, they were angry,” Jackson said in a 2016 interview with The Weekly Challenger. “We lost friendships with some of those guys. Some of them stopped speaking to us.”

Some were more direct in their disgust, telling the black officers that they should be kicked off the force, or worse, that they should never have been police officers. They felt the black officers were against them. Some white officers even went so far as to say that if the 12 found themselves in trouble and calling for backup, they would simply not respond and leave them to their fate.

“We weren’t against them personally,” Jackson explained. “We were against the system.”

Yet some of the white officers, Jackson noted, were supportive even though very few did so openly for fear of retaliation or being ostracized themselves.

Crawford agreed in that same 2016 interview, saying, “There were some good guys.”

Nearly a year after the officers put the suit in motion, they went to court on two different days, March 31 and April 1, 1966. Here they received support from fellow policeman Bob Stokes, a white officer who spoke on their behalf and testified — in front of the chief of police who was present in the courtroom — that the black officers were not being treated fairly.

Attorney Frank Peterman Sr., who took on the intrepid lawsuit along with Sanderlin, couldn’t recall ever taking on a similar case up to that point.

“I think it was precedent-setting for the nation, to some extent,” said Peterman Sr. back in 2016.

Despite opposition that they knew would come their way — he admitted he even received threats from the Ku Klux Klan — Peterman Sr. believed they could win because they had faith in the judicial system. “We were dedicated to justice.”

In the end, they lost the case.

But Sanderlin wasn’t done. He urged them to appeal. The officers had bankrolled the lawsuit themselves and told him they simply didn’t have any more money. Here the attorney suggested they contact the NAACP for assistance in their plight. The organization indeed stepped up and took on the costs, and on August 1, 1968, the appeal was successful.

The court awarded them a victory. In a year’s time, Crawford was patrolling a primarily white area in northeast St. Pete.

After retiring from the force, Crawford continued his efforts to address and eradicate segregation. He went to work for the Community Relations Service division at the U.S. Department of Justice where he used his experience with conflict resolution to resolve racial tensions in various communities across the country.

Mayor Rick Kriseman presented Crawford and Jackson with awards for their service to the St. Petersburg Police Department in 2015.

Crawford led in other ways, producing positive results and leaving a strong, uplifting legacy. Native son Charles Fulwood reflected his impact.

“I was in Gabon (a country along the Atlantic coast of Central Africa) right after my daughter was sick. I saw a brother that just looked like Freddie. It reminded me that African people are familiar. It made me feel a bit home bound. Freddie was a quintessential man,” said Fulwood, a widely published writer.

Crawford and other black police officers organized a Boy Scouts troop in the black community. The national Boy Scouts organization dodged the issue of desegregation by leaving it to local councils to decide on whether or not to admit black children.

Some councils admitted black youth but prohibited them from wearing the scout uniform. Fulwood remembers Boy Scout officials in Richmond, Va., once threatened to stage a public burning of Scout uniforms if black boys were permitted to wear them.

“Freddie and a small group of black police went through a long obstacle course to get our charter as Troop 206, or was it 202,” said Fulwood, who couldn’t quite recall.

He remembered the troop’s first camping trip in the late 60s to an unincorporated area of Pinellas Park near Clearwater. The officers were doing all of this on their own time, stealing time away from being on duty.

“Once we were all camped down, Freddie and the other police officers left to go back to duty about 10 miles away. We were in an all-white area at the time, tolerated intruders on the strength of police officers – even if they were ‘colored.’ At least it was the harmless activity of camping to ‘rehabilitate some colored boys.’ “

On that fateful day, one of the boys set the woods on fire trying to light a cigarette. Fire trucks and police cars came from all over the county. Crawford, King, and other black cops came racing from St. Pete.

“We never went camping again. I’m surprised, in hindsight, that they were not fired,” Fulwood said.

From that point on, there were no more camping trips for the young men, but Crawford did steer Fulwood toward the Police Athletic League (PAL) where he learned how to box as an amateur welterweight.

As Crawford used to warn him: “Fulwood, you always fighting, fighting the big boys––you’re a runt, better learn how to pug fundamentals, son,” recalled Fulwood.

Crawford told him that PAL would teach him discipline, technique and character. He also warned him to stop jumping on the “big boys” just for fun.

Crawford’s leadership and guidance helped Fulwood live a disciplined, character-fueled successful life that includes the operation of an influential strategic communications firm in Washington, D.C.

***

Homegoing services for Freddie Lee Crawford are set for 10 a.m. on Saturday, June 1 at First Baptist Church, 1900 Gandy Blvd., St. Petersburg.

A wake is scheduled for Friday, May 31 at New Jerusalem Missionary Baptist Church, 1717 18th Ave. S. The family will gather from 4-6 p.m. The public may visit from 6-8 p.m.

In lieu of flowers, the family is requesting donations be sent to the Jordan Park Projects Nostalgic Association, Inc. at P. O. Box 12263, St. Petersburg, FL 33733.

Crawford, a native of St. Petersburg, is survived by four daughters, Joan (Roger Louis) Crawford, Peggy Crawford, Traci Crawford, and Kimberly Crawford; five sons, Frederick (Veronica) Crawford, Quinton (Marva) Harris, Terryl Crawford, Norman Crawford and Kofi Adisa; two sisters, Verdell Wyman and Shirley Tigg; one brother, Arthur Lee Crawford; an aunt, Vann Lou and a host of grandchildren, great-grandchildren, nieces, nephews and cousins.