From left to right, Emerald Morrow, Frank Wiley and Miranda Parnell presented Channel 10’s ‘Our Heart, Our Hope, Our History’ documentary on Feb. 7 at The Woodson African American Museum of Florida.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The Woodson African American Museum of Florida hosted a special viewing on Feb. 7 of WTSP-10 Tampa Bay’s Black History Month mini-documentary that explores the rich Black history in the Bay area.

The documentary first explained the origins of Black History Month. In 1915 historian Carter G. Woodson and minister Jesse Moorland founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, a group dedicated to preserving and promoting Black excellence.

Woodson, considered the “father of Black history,” launched Negro History Week in the second week of February 1926 to coincide with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass. It wasn’t until 1976 that this observance was expanded into a month-long celebration.

Dr. Gary Lemons’ artwork is hanging at The Woodson African American Museum of Florida.

“Black history is about the history of survival,” said Dr. Gary Lemons, a USF professor of African American Literature and Biblical Studies.

Lemons is also an artist with an exhibit currently displayed at the Woodson Museum.

“We can be different and have Black communities,” he said, “but let’s have one communal love for who we are as Black people on this land where we were never meant to survive.”

His most recent work focuses on reaching hands of all shades, illustrating the value of love for all humanity.

The NAACP has been “bread and water” to many Black people, said Queen Miller, a former educator and NAACP member for decades. Her grandfather was born into slavery, so she knows the value of freedom and has spent her life uplifting her community and preserving the history.

Miller believes people need to know African-American history, and she is puzzled by the efforts of Gov. Ron DeSantis to curtail the teaching of Black history in state schools and colleges.

“I don’t know what it’s all about. I think the governor said it wasn’t unnecessary,” she said. “He might not have run into all that lynching and stuff where he was raised at.”

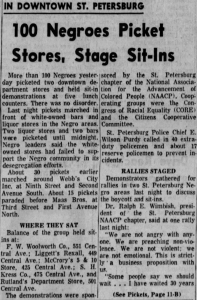

Sit-ins and sacrifices

The Woolworth lunch counter sit-ins were a turning point for Tampa in the civil rights struggle. Led by Clarence Fort, on Feb. 29, 1960, students marched through Tampa into the F.W. Woolworth store and sat at the lunch counter, where only whites could sit and be served.

Clarence Fort and Arthenia Joyner visited the historical marker outside the old Woolworth store on the corner of Polk and Franklin Streets in Tampa.

Fort and Arthenia Joyner returned to the site in 2023, as documented in the 10 Tampa Bay special.

“We knew that we couldn’t,” recalled Joyner in the documentary, “but we decided that we would.”

Joyner was just 16 at the time of the protest, and Fort was 20 and the president of the NAACP Youth Council. Fort recalled sitting right down with young protestors following suit all around him.

“Most of them didn’t even have money,” he remembered with a chuckle. “We couldn’t have bought sandwiches if they sold it to us — but they didn’t know that!

A St. Petersburg Times article published on Dec. 30, 1960, on integrating St. Pete’s public spaces.

It was the first of five days of marching, taking a seat at the counter, being refused service, and leaving. On the second day, the mayor sent about 10 officers, Fort recalled, to stand behind the protestors so no one could get to them. That was a difference between Tampa and other Southern cities, he said.

After the fifth day, Mayor Julian B. Lane, Rev. Leon Lowry and others formed a biracial committee to “work it out,” Fort said. The City of Tampa integrated its lunch counters that September and Fort believes that was a turning point.

Fort then turned his attention to the segregated bus lines and went on to become the first Black driver for Trailways bus line in Florida.

Joyner also continued to fight for what she believed in, as she was arrested in 1963 for protesting segregated theaters. She later became a state senator.

“I’m not going to stop fighting for change,” Joyner said.

A historical marker outside the old Woolworth store on the corner of Polk and Franklin Streets in Tampa shares their story.

“You still have to challenge the status quo,” Joyner stressed. “Change does not occur if you become stagnant.”

Historic Black neighborhoods

The documentary also explored such communities as the Deuces in St. Pete, which during segregation, was home to more than 100 businesses, including the Manhattan Casino. Countless African-American performers played at the Manhattan, a stop on what was known as the “Chitlin’ Circuit.” Legends like Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Nat “King” Cole and James Brown all performed there in its heyday, but time brought about change.

The 22nd Street Corridor, affectionately known as the Deuces, was home to more than 100 Black-owned businesses during segregation and has been called St. Pete’s Black Wall Street.

“When you look at the corridor, one of the things that destroyed 22nd Street’s vitality was the I-275 interstate,” explained Veatrice Farrell, executive director of Deuces Live.

This story is familiar to the historic Gas Plant district, where homes and businesses were uprooted during the construction of I-175 and Tropicana Field. This sort of uprooting is not peculiar to St. Pete, as many neighborhoods in the Bay area have suffered a similar fate.

“Every one of these neighborhoods has a slightly different twist that led to their end,” explained Rodney Kite, a Tampa Bay History Center historian.

Dobyville, a thriving Black community in Tampa’s Hyde Park, was destroyed by expressway construction and gentrification. The Garrison neighborhood was one of the first Black-owned neighborhoods in Tampa, yet today few signs of it remain.

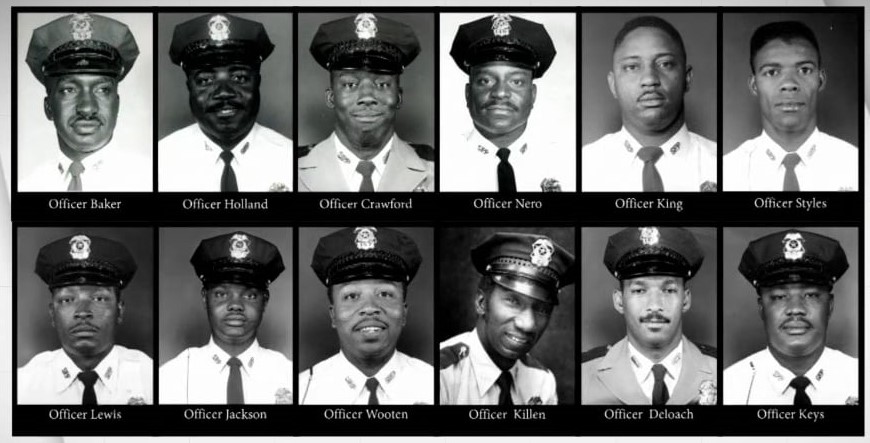

Segregation affected Black lives everywhere, and officers of the law were not immune. Before the St. Petersburg Police Department became integrated, Black officers could not work in white neighborhoods and could not arrest white suspects. They were routinely subjected to racist treatment and glaring inequalities within the department.

The Courageous 12

Leon Jackson and 11 of his African-American colleagues decided to take a stand and sued the city for discrimination. They became collectively known as the “Courageous 12.” Jackson, who became on officer in 1963, is the last surviving member.

“We were just a half police officer,” he said. “They didn’t call you Black and African American during that time.”

The police practices were racist, he said, and recalled that they were dismissed when they asked for much-needed new patrol cars because they were working in the “colored neighborhood.” Their white counterparts in the police station often ignored them outright.

“Those guys used to walk by us and wouldn’t even speak,” he said, adding that when he and his fellow Black colleagues took these concerns to their superior officers, they were brushed off, and told not to be “so sensitive.”

The Courageous 12 filed a lawsuit in 1965, documenting the insults they endured, their lack of authority and their outdated cars. Initially, in a Tampa federal court, a judge ruled against them, but in 1968, the NAACP advocated with an appeal, and the Fifth Circuit Court in New Orleans ruled in the officers’ favor.

“We were the Jackie Robinson of police integration,” Jackson said.

Jackson wrote about this struggle in his book “Urban Buffalo Soldiers.”

Black history as American history

These days there is an ongoing debate on how African-American history should be taught in schools. Last month, the Florida Department of Education rejected an AP African American Studies course for high school students, saying it “lacks educational value.”

“If we are really to teach American history, there’s no way to do it and not include the history made by Black people,” said Fred Hearns, curator of Black History at the Tampa Bay History Center.

State Senator Geraldine Thompson pointed out that of the 67 school districts in Florida, only 12 are considered to be doing an “exemplary job” in teaching African-American history.

Saving erased Black cemeteries

Another issue the documentary pointed out is the discoveries of the “erased” and “lost” African- American cemeteries throughout the Bay area. Such cemeteries — Zion in Tampa, Evergreen in St. Pete and a beneath Missouri Avenue in Clearwater, to name a few — had been built over during various development projects over the years.

“Consideration was not given to Black people during that time, and we are still having to fight those battles today,” noted Zebbie Atkinson IV, president of Clearwater/Upper Pinellas NAACP.

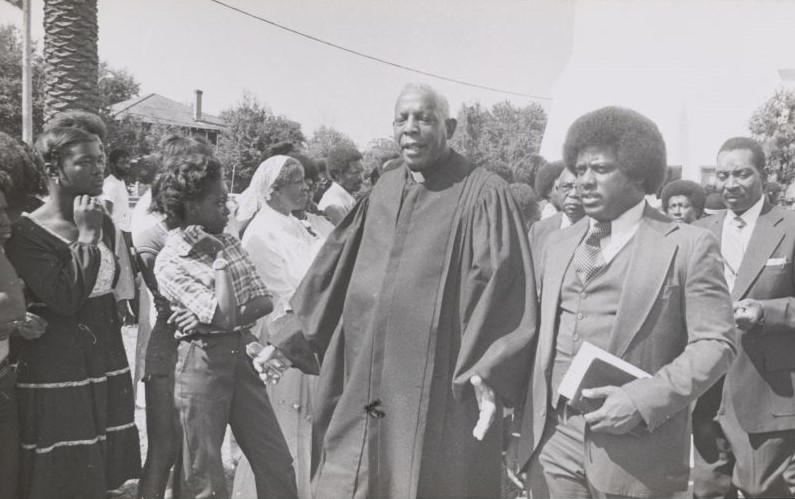

Finding refuge in faith

Churches play a vital role in Black history, often serving as the hub of the community, even in the face of adversity.

Rev. Enoch Davis and Rev. Wayne G. Thompson in the 1970s.

“The fact is that when we opened our churches, it is because the white church didn’t want us a part of that,” said Rev. Wayne Thompson, senior pastor of First Baptist Institutional Church in St. Pete.

Longtime members say that generations of this congregation have managed to stay together through forced moves, pandemics, and Jim Crow.

“It’s like home,” said Maxine Feazell. “It’s like home. Family, love, it’s all here.”

Bethel AME is the oldest church in St. Petersburg.

The Historic Bethel AME Church is St. Pete’s oldest church, said Rev. Kenny Irby. Some parts of it feel more like a museum, with century-old artifacts. Black churches are a part of history, the pastor believes.

“Dr. King and the Freedom Riders, they were all really committed to using the network of churches, regardless of denominations, right? It was God’s house,” said Irby.

Harlem of the South

The documentary also noted that for a time, Tampa was known as the Harlem of the South, and Perry Harvey, Sr. Park stands in what used to be an epicenter of Black America. It featured bustling Black businesses and culture, including the first library for African Americans in the city, but it was the entertainment that brought Tampa’s Central Avenue to life.

Tampa’s Central Avenue in the 1940s. Photo: Tampa Bay History Center

“People came from miles around to see the entertainers,” Hearns pointed out, “to enjoy their performances and to eat at those restaurants that served chitlings and collard greens and candied yams.”

Ray Charles made his first recording a block away from Central Avenue in 1950 — a tune called “St. Pete Florida Blues.” Hearns explained that though Charles wrote and recorded the song in Tampa, he believed white people were more familiar with St. Pete and its beaches, and he would have a better chance of appealing to white audiences with that title. Today, Ray Charles Boulevard stands two blocks from where he recorded the song.

The Cotton Club on Central Avenue played host to some of the all-time greats, including Duke Ellington and Ella Fitzgerald. Today the street is gone, but a colorful mural remains, featuring Charles at the piano, Fitzgerald at the microphone and a couple doing the twist, immortalizing the spirit of the Harlem of the South.

After the documentary, audience members enjoyed a panel discussion with Jackson, Hearns, Farrell, and Atkinson IV.