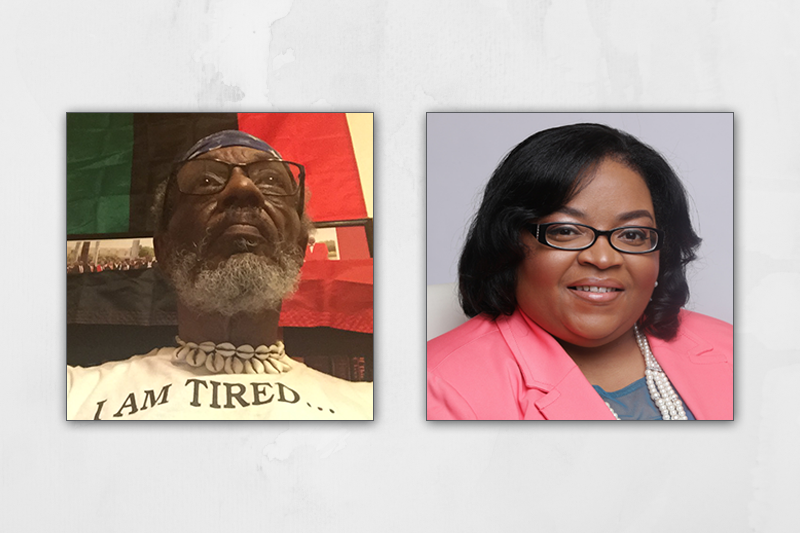

J. Carl Devine, director of the Banyan Tree Project, and Leisha McKinley-Beach, a 30-year-HIV and AIDS activist, discuss the impact of racism on HIV/AIDS health outcomes in the Black community.

By J.A. Jones, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – J. Carl Devine, director of the Banyan Tree Project, and Leisha McKinley-Beach, a 30-year-HIV and AIDS activist, sat down to discuss the impact of racism on HIV/AIDS health outcomes in the Black community on WUJM/99 Jamz last month as part of The Weekly Challenger’s #PinellasEHE initiative.

McKinley-Beach immediately clarified the issue: “I’m not going to do this dance of the lightweight stuff — let’s just dive right in here and start talking about how racism has gotten us to where we are right now in the trajectory of HIV in this country and in the state of Florida.”

Devine took time to “give a shout out” to Brandi Knight, who was recently appointed as interim administrator at the HIV/AIDS Section at Florida Department of Health – and the first Black person to ever be in the position.

The fact that it took the FDOH this long to appoint a Black woman, and the fact that even in the face of long-term advocacy, the department still hadn’t appointed a same-gender-loving Black male “in any position of authority in the state of Florida after 30 years of this,” was, stated Devine, an on-going pattern of racist behavior.

“We tried for years to get Tom Liberti (former Bureau Chief at Florida Department of Health) to have someone from our community to address the issues within our community. And he didn’t do it.”

Devine said that due to Liberti’s positions, “a lot of us died that did not really have to die; a lot of us have suffered for years because of his decisions. Racism in Florida is very prevalent, particularly in the Department of Health.”

McKinley-Beach questioned what FDOH’s stance regarding who led departments ultimately said about the department’s outlook on Black leadership and the fight to end HIV in the state of Florida.

Devine blamed systemic racism that not only minimized the impact of Black leaders, but deliberately undermined and destroyed the Black-led agencies that did exist. “They helped us to fail; they created situations so that we could fail.”

Calling the still-existing racism a “diabolical monster,” Devine asserted that the health disparities existing in the Black community are intentional.

“When the first diagnoses came about, they didn’t pour money into Black agencies or Black communities to help Black people. All of the monies went to white agencies — and when we went to those agencies for help, they treated you like you were not even human.

Devine added that this wasn’t just something of the past, but that this situation and condition is continuous.

McKinley-Beach noted that Florida has a unique infrastructure in which lead agencies orchestrate the HIV care service delivery models within the various Florida jurisdictions. Noting that she wasn’t aware of any Black-led lead agencies in the state.

Devine pointed to “dollar bills and control,” stating that although Black leaders have been on the ground for years, they are not at the table where the decisions about what happens in Brown and Black communities are being made.

“The white folks make the decisions and then they color them Brown and Black and purple, and those other colors, but it’s not coming from us, it’s coming from them.”

When the money flows into white-led organizations, he continued, not only do Blacks not see it, but they aren’t usually offered the grants necessary to service their communities – and if they are, they’re so small that it takes several grants put together to enable a program to run.

Devine noted that discrimination is so blatant because “we don’t have a lot of people fighting for us; even though we vote for these politicians, there are very few of them that have ever come to me and said, ‘What can I do to help you do what you do better in this community?’”

The Banyan Tree Project director lamented that he missed Rudy Bradley – former District 55 Black representative who won the Republican seat from 1994 to 1998 before switching parties to win as a Democrat in 1999 – and subsequently switching back and losing in District 21 in 2000.

Devine recalled directly going to Bradley while he was in office to share concerns about substance abuse and HIV in the Black community. He said Bradley went to work providing money and resources in our community.

“We have not had a representative to do that since,” he pondered.

McKinley-Beach followed up by noting that the undermining of Black leadership around HIV was not only a health issue, but it was also a political, social justice issue and economic issue.

She relayed that it’s important to bring all those factors into the conversation, even as a new “view” of the AIDS crisis is being touted outside of the Black community. “There have been some conversations around no longer using the term AIDS — that the term is stigmatizing,” stated McKinley-Beach.

But, she added, “We’ve got to be careful about whose bandwagon and whose movement we jump on, because there are some communities who are not seeing people die from complications related to this virus — they’re able to celebrate viral suppression.”

Viral suppression occurs when individuals diagnosed with HIV are taking their medications as directed, to the extent that the viral load in their system becomes undetectable, and therefore, untransmittable.

McKinley-Beach cautioned, “This is not our story, because there are still communities where we are seeing Black people, young Black people who are dying from complications related to AIDS. And so, until CDC changes that terminology, AIDS is still a word in my vocabulary.”

“And mine too,” Devine agreed.

To reach J.A. Jones, email jjones@theweeklychallenger.com