Author and historian Dr. Raymond Arsenault and civil rights leader Dr. Bernard LaFayette, Jr. discussed the legendary civil rights activist Congressman John Lewis and Arsenault’s new biography, ‘John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community.’

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — Author and historian Dr. Raymond Arsenault sat down with civil rights leader Dr. Bernard LaFayette, Jr. at Allendale United Methodist Church on Feb. 22 to discuss legendary civil rights activist and Congressman John Lewis and his new biography, “John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community.”

The event, “In Search of the Beloved Community: A Conversation with Raymond Arsenault,” was presented by Allendale in partnership with Tombolo Books and the League of Women Voters of the St. Petersburg Area.

Before retiring, Arsenault was the John Hope Franklin Professor of Southern History Florida Studies program co-founder and Senior Scholar at the University of South Florida. He’s the author of several books, including “Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice,” “The Sound of Freedom,” about Black opera singer Marian Anderson and “Arthur Ashe: A Life,” about the famed African-American tennis player.

In his biography of Lewis, Arsenault traces Lewis’s upbringing in rural Alabama, his activism as a Freedom Rider and leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), his championing of voting rights and anti-poverty initiatives and his decades of service as the “conscience of Congress.”

Arsenault met Lewis — whom he called “the most extraordinary person that I’ve met in my lifetime — over two decades ago while compiling research for “Freedom Riders,” as Lewis was organizing reunions of the Riders, who were scattered all over the country.

He met LaFayette, a longtime friend of Lewis’s, around the same time. LaFayette, a civil rights activist, minister and educator, co-founded SNCC in 1960. He was a leader of the Nashville Movement and on the Freedom Rides in 1961, where Black and white activists rode on buses together across the segregated South to test the Supreme Court decision that declared segregation on interstate buses unconstitutional.

Lewis himself was controversial within the Civil Rights Movement, Arsenault explained, because of his deep commitment to nonviolence for the “beloved community.” He never wavered, even in the face of the emerging Black Power and Black Nationalism Movements and the criticism of interracial coalitions and nonviolence as a method.

“He was sort of in the way,” he said, “and in 1966, after three years as the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, he was basically thrown out and replaced by Stokely Carmichael.”

Arsenault said Lewis and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. believed that “you’ve got to love your enemies as much as you love your friends,” which is not easy.

“Maybe we need to hear that more than ever,” he said, “but it’s probably more difficult than ever.”

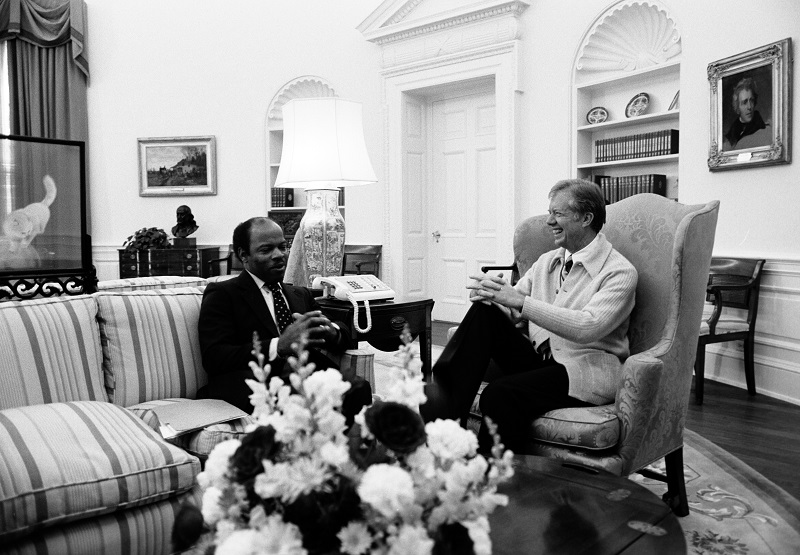

In 1968, while Lewis was working on the Robert F. Kennedy campaign for the presidency, Dr. King was assassinated on the night when Lewis was helping Kennedy at a rally in a predominately Black section of Indianapolis. Though they learned of King’s murder in Memphis that night and were devastated by it, Lewis and Kennedy proceeded with the rally, and Kennedy “probably gave the best speech of his life that night,” Arsenault said.

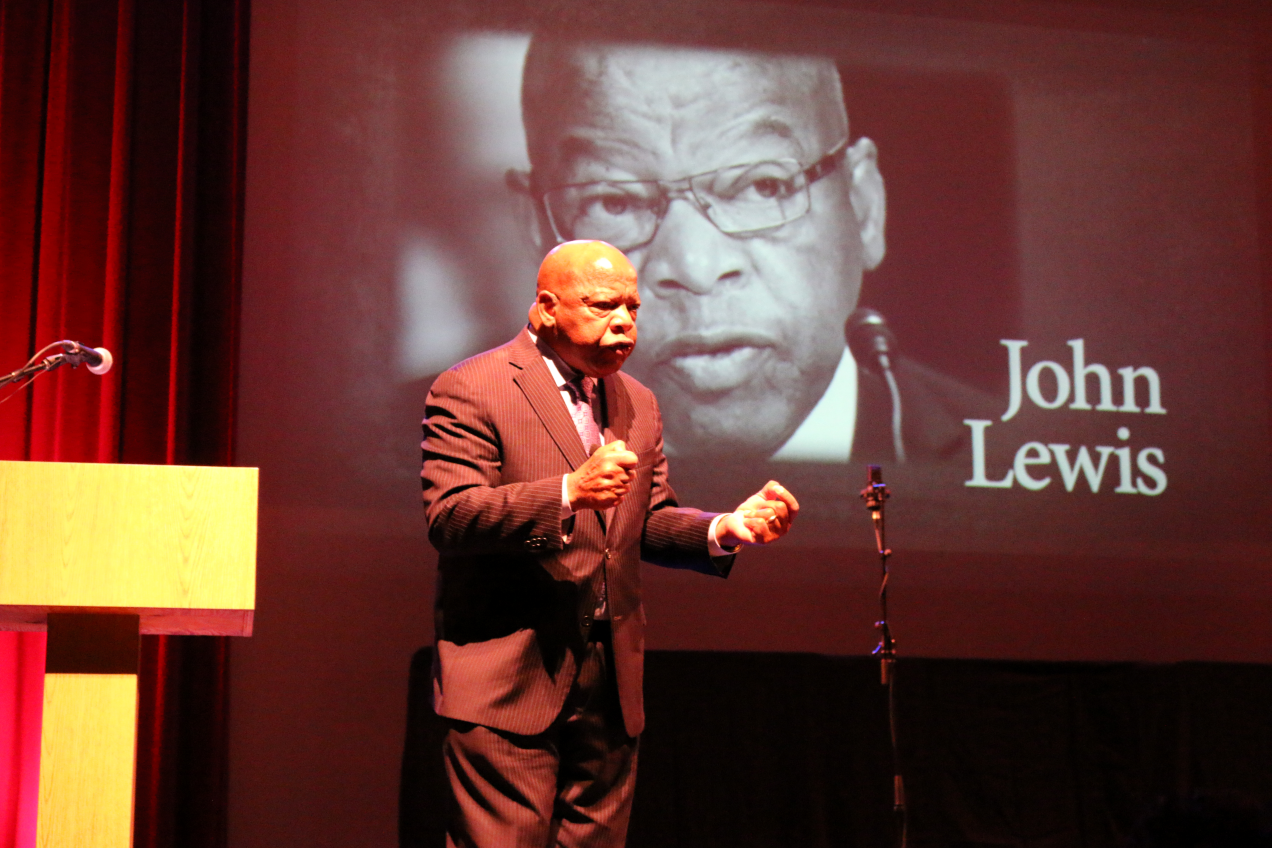

The late Congressman John Lewis at the Poynter Institute’s 100th anniversary celebration of the Pulitzer Prize on March 31, 2016.

“Indianapolis turned out to be one of the few cities in the United States, large cities, that did not go up in flames that night,” he said.

A liberal white journalist asked Lewis why is that those who are fighting for freedom are the ones getting assassinated and even told him, “Maybe we should put a bullet in one of their heads,” Arsenault related. But immediately, even though he was grieving terribly, Lewis told the journalist, “The world does not need any more hate!”

To Arsenault, that was the quintessential Lewis — a man who always seemed to keep his head. Nonviolence, for Lewis, was not a tactic or mere strategy but a way of life. He didn’t simply seek equal rights in the movement but a “revolution in the human heart,” Arsenault pointed out.

LaFayette, a Tampa native, was the editor of his high school newspaper and earned a journalism scholarship to Florida A & M University, but his grandmother told him outright that he would not be a journalist but a preacher because a mark on his forehead preordained this, LaFayette recalled. Determined, his grandmother — who only had a third-grade education — did research and found a college in Nashville, American Baptist College. LaFayette went there on a work scholarship in 1958. Arriving in Tennessee weeks before school began, he did odd janitorial jobs and cut grass, living off the cans of sardines and other foods that his church had given him as a going-away gift.

“I worked at the college before it even opened,” he remembered, “so I got the best room on campus!”

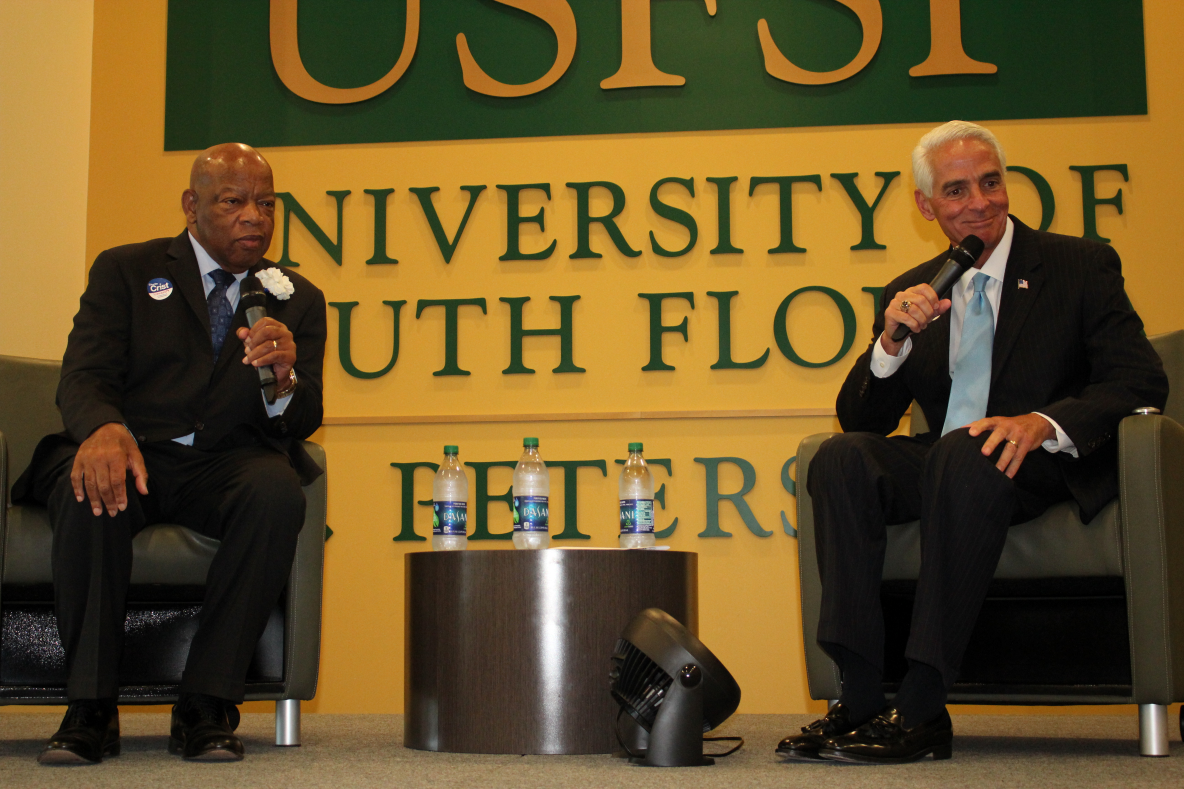

The late Congressman John Lewis at USF St. Pete gave a hand to the Charlie Crist campaign on Nov. 2, 2016.

Lewis, who was a year ahead of LaFayette, became his roommate. LaFayette quipped that he had the advantage of rooming with someone who had already taken all the courses he would take.

“That’s how we got to be roommates, and I didn’t have to buy any books!” he said.

Lewis was the president of his class, so he was already a leader, a quality that impressed LaFayette. He underscored that theology and the study of Scripture give you the basis for nonviolence, and through that, “somehow you have the ability to bring about change when you represent the change that you want to see.”

Lewis was very bright, LaFayette recalled, as he could not only recite what he had read in books but also interpret what he read and put things together. He went on to become president of the entire student body.

At Fisk University in Nashville, where Lewis and LaFayette were at a SNCC meeting, Carmichael suggested electing a leader through elimination rounds of multiple candidate voting, which LaFayette agreed to — but turned around and told everyone to vote only for Lewis, who was elected as the organization’s leader.

LaFayette and Lewis led sit-ins in Nashville, which helped desegregate movie theaters and the Greyhound bus station in 1960. It did not come easy, though. LaFayette recalled getting locked in the bus station overnight with all the lights turned off by the white management.

When the management finally opened the doors to let him out in the morning, LaFayette entered a phone booth in the parking lot. The next thing he knew, a driver had kicked in the door, put him in the headlock, and thrown him on the concrete. The driver then kicked LaFayette in the face.

The late Congressman John Lewis frequently visited St. Pete, as seen above, with the late Watson Haynes and Charlie Crist.

“I got back up,” he said, “and they didn’t know what to do because what they did didn’t work. And I looked at him, and I said, ‘Excuse me, I need to finish making my phone call.’ I didn’t respond to them at all. I just accepted that response. The police came and arrested me.”

As two officers led him to the police wagon, the younger officer asked the senior one what they would charge LaFayette with. “Fighting,” came the response from the senior officer. “Who with?” asked the younger. The senior one then instructed him to go get “one of those,” gesturing to the white cab drivers. They put the handcuffs on the white driver as well, though they threw LaFayette into the wagon first. The driver seemed frightened to be in the wagon with him, LaFayette recalled, but he told the driver, “Listen man, relax, I’m the same on the inside as I am on the outside. That had a double meaning.”

Lewis was no stranger to punishment during the turbulent times of the Civil Rights Movement, Arsenault said, noting that he suffered several beatings, a fractured skull and was imprisoned 45 times in his life, including five times when he was a member of Congress.

He related a story where Elwin Wilson, a former white supremacist, called Lewis on the phone, sobbing and apologizing for his behavior and the bloody beatings he gave Lewis when they were both younger. Lewis had him flown to Washington, where they had an in-person “come to Jesus meeting” and became friends.

With Arsenault’s help, they, along with former Freedom Riders, were featured on an episode of Oprah Winfrey’s talk show. As Wilson was visibly petrified and sat frozen at the outset of the episode’s taping, Lewis reached out and grasped Wilson’s hand, raised it a bit, and told everyone, ‘He’s my brother,'” Arsenault recalled.

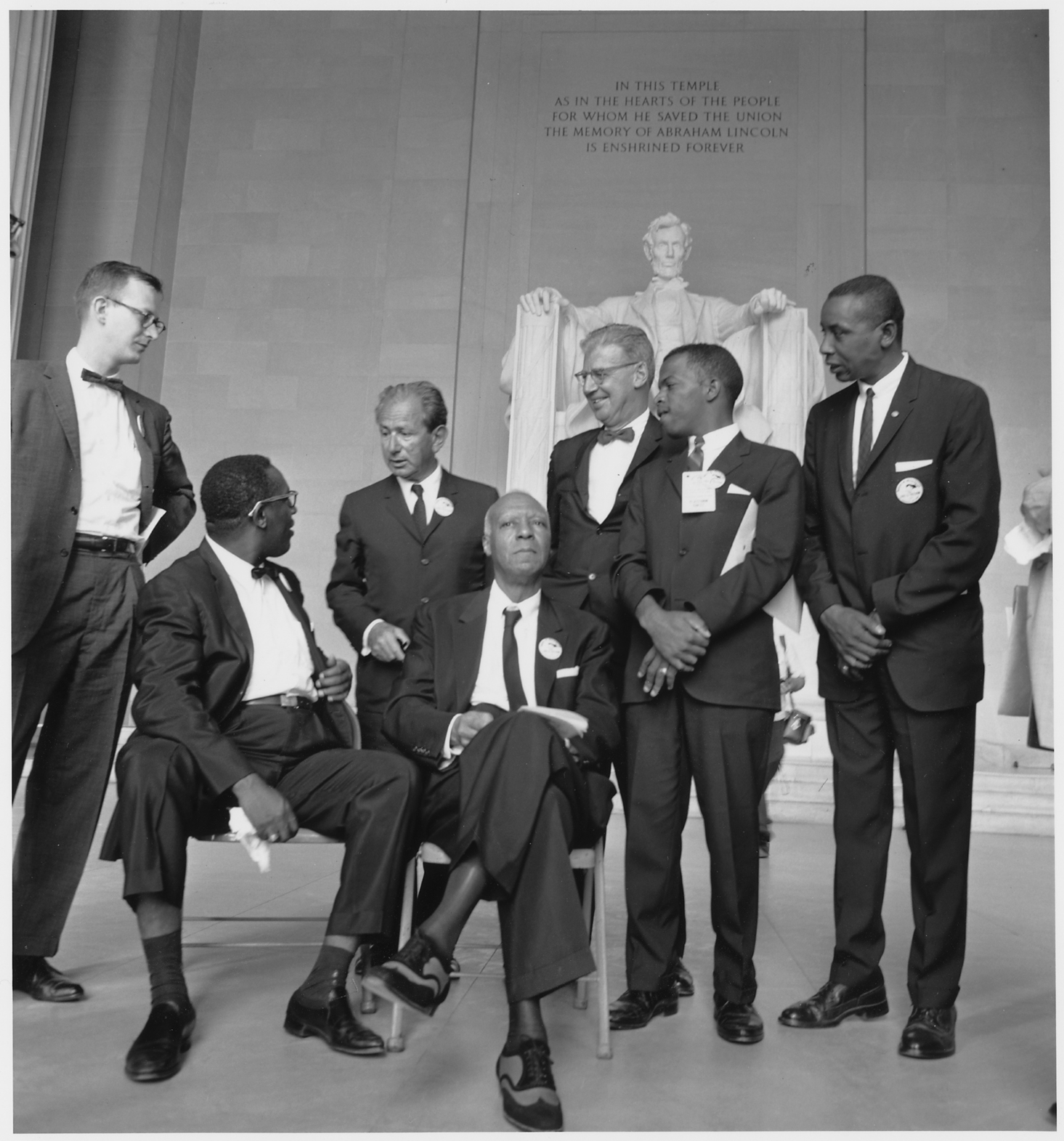

Civil rights leaders meet with President John F. Kennedy and Vice President Lyndon Johnson after the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, 1963. Lewis is fourth from left. [Public Domain]

Lewis urged Lafayette to join the Freedom Rides, and on a bus from Birmingham, Ala., to Montgomery, Ala., the streets were empty on a Saturday morning. Lafayette and the other Riders felt something was amiss. LaFayette then stood up and instructed everyone on the bus to find a partner and stick with him “no matter what happens.”

An Alabama state guardsman on the bus promptly told him to “sit down and shut up,” to which LaFayette said to him that he may be in charge of the troops but not the Freedom Riders. LaFayette was in charge of them. The guardsman, not used to being told off by young Black men, said nothing. Then, the calm was broken. A mob came out of the bus station and started beating up the reporters and cameramen who had been there, LaFayette recalled, ignoring the Riders. They wanted to “wipe them out” first so they couldn’t record anything.

“I knew we were going to be next,” he said, adding that he then tried to get the women into the lone cab that was there, even though they had expected several to be waiting for them. “When they got in that cab, that Black cab driver jumped out! [He] jumped out of his cab, shaking like a leaf!”

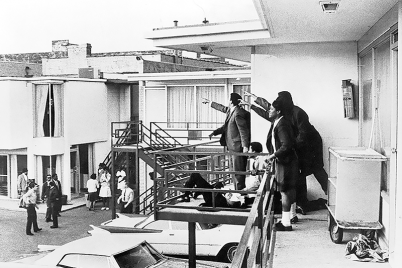

Lewis said he admonished him, telling him to get the women out of there, but the driver outright refused to drive the white women. When the mob had finished beating the reporters, it turned its fury on the Riders. One of them hit Lewis on the head with a Coca-Cola crate, LaFayette said, and a metal part of that crate put a hole in his head. They knocked another white Rider unconscious, even knocking all his teeth out.

The more activists like the Riders were beaten up and even imprisoned, the more they kept “singing these freedom songs” and employing their stance of “unmerited suffering,” as they didn’t respond to the usual forms of intimidation, Arsenault said.“There was no turning back for them,” he said. “I mean, they kind of got their stripes, in a sense. They were kind of nonviolent warriors.”

Lafayette said that while imprisoned, they turned their cell into a college, urging students of various majors to give lectures during the day while at night, they sang songs. While in jail, they had 40 days to put up an appeal bond or be forced to serve the entire sentence. They used 39 days, Lafayette said. That’s how they kept the jails filled and used them as a “power base for our change,” he explained.

They won over the night warden in a Mississippi jail, entertaining him with their singing, even inserting his name into the lyrics. The warden began sending out a “trustee,” an inmate who could be released for a few hours and return to fetch ice cream for everyone. LaFayette and others even helped him with his daughter’s college application. When it was time for them to be transferred to a state prison, LaFayette said the night warden saw them off, even telling them to “Come back and see me, hear?”

LaFayette said that today, there are groups around the country and abroad that offer training for effecting social change through nonviolence.

“We train people so they can train others,” he said of these groups. “This is something that I do as chairman of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the group that Martin Luther King organized,” adding that SCLC played a role in helping Nelson Mandela get elected as South Africa’s first Black president.

As John Lewis was famous for getting in “good trouble,” as he put it, Lafayette faced some pushback from his own family when he did the same. When he needed his application for the Congress of Racial Equality before he could go on the Freedom Rides, he sent it to his father in Tampa for his required signature. Concerned about how long it took to receive the signed form in the mail, LaFayette called his father and asked if he had received the form. He told his son he had, but also told him: “I’m not signing your death warrant.”“In part, my family admired what I was doing,” he admitted, “but at the same time, they didn’t want to see me get eliminated!”

Though LaFayette could not participate with Lewis on that Freedom Ride, he was determined to go on later ones, which he ultimately did.

Arsenault credits LaFayette with helping him finish “John Lewis: In Search of the Beloved Community.” When he started writing the book, Lewis was almost immediately diagnosed with pancreatic cancer. He said he didn’t feel right about bothering him in his final months, so he didn’t get to do final interviews. Knowing Lewis for more than 60 years, LaFayette stepped in, answered endless questions and filled in some gaps.

“If you can’t have John Lewis here tonight, this is the next best thing,” asserted Arsenault.