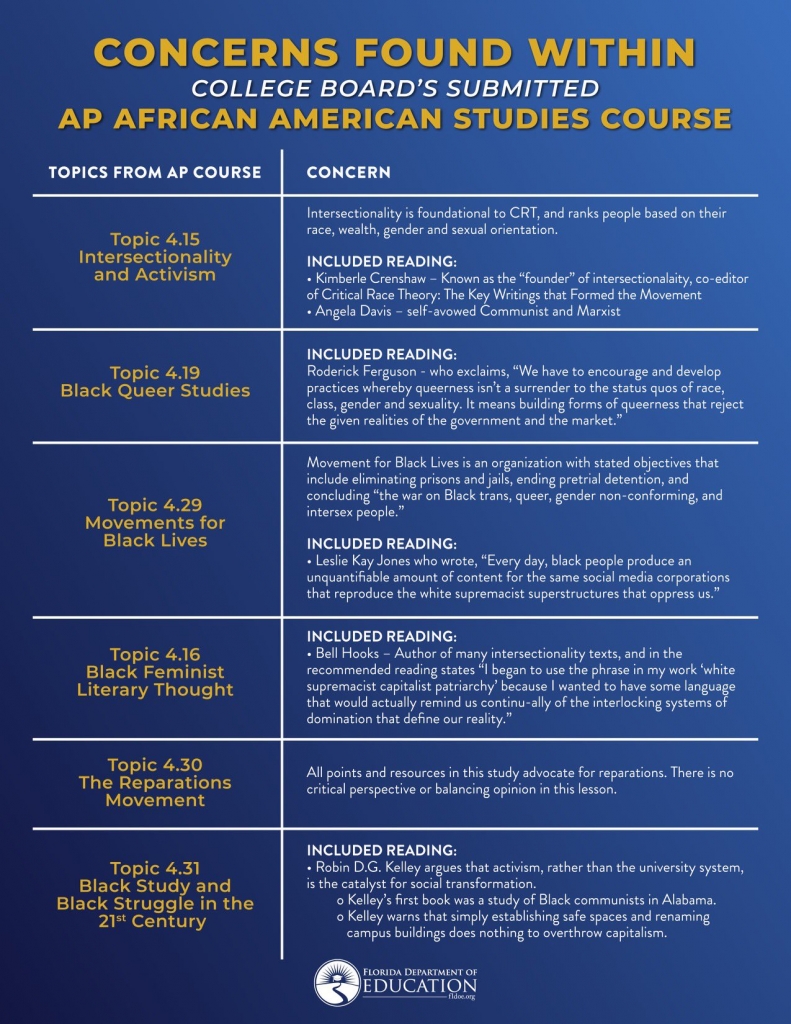

The College Board’s latest version of the AP African American Studies course includes teachings on intersectionality and Black feminism but makes instruction on the Black Lives Matter Movement and reparations optional.

BY NANCY GUAN | WUSF

The College Board, which oversees the Advanced Placement curriculum and exams, has released the final version of its AP African American Studies course. It has drawn intense scrutiny after being embroiled in controversy over the last year.

Set to officially launch for high school students next fall, the latest iteration includes teachings on intersectionality and Black feminism but makes instruction on the Black Lives Matter Movement and the reparations debate optional.

The Miami Herald’s review of the 300-page course framework pointed out that topics on the Black queer experience were omitted. But the course included Black authors such as Kimberlé W. Crenshaw, a leading scholar on critical race theory, and Angela Davis, a political activist with ties to the Black Panther Party.

A College Board spokesperson said the revisions were based on feedback from students, teachers and higher education faculty, and not the political controversy with Florida state officials that erupted earlier this year.

According to a statement, the nonprofit worked with over 300 African American Studies scholars, high school AP teachers and experts within the AP program over the last three years.

Other changes include increased time dedicated to the Tulsa Massacre and athleticism within the Black community.

But whether or not the state of Florida will accept the AP class in its course directory for next school year remains to be seen.

The State Department of Education did not return WUSF’s requests for comment.

College Board spokesperson Kelsey Latomia said their team will work on submitting the course to state education systems in the coming weeks.

AP course caught between political crossfire

Pilot versions of the course have been taught in more than 700 schools across 40 states in the last and current school year. A private school in Miami-Dade County was the sole Florida school to participate in the pilot.

Disputes over the pilot versions of the course erupted when the Florida Department of Education rejected the course in January over “woke indoctrination” accusations. Florida officials continued to clash with the College Board in the following months.

Florida Commissioner of Education Manny Diaz Jr. called the material “obvious violations of Florida law,” as the state, in recent years, has passed a slew of legislation restricting discussions on race, gender and sexual orientation in K-12 classrooms.

“As we’ve said all along, if College Board decides to revise its course to comply with Florida law, we will come back to the table,” Diaz posted on X, formerly Twitter.

When the College Board released a revised version for the second year of the pilot in February, the company then drew criticism from the left. Scholars and activists blasted the curriculum for being watered down and accused the board of bending to political pressures.

The College Board denied the notion that Florida’s criticisms influenced the new framework and maintained that changes to the course were in place before the state raised objections.

However, in April, the College Board announced that further revisions would be made and that they were “committed to providing an unflinching encounter with the facts and evidence of African American history and culture.”

Educators weigh in on the new course

According to University of Florida African American Studies program director David Canton, criticism of the final version of the AP African American Studies course is inevitable.

Canton worked as a faculty ambassador with the College Board, contacting universities nationwide for their input on the AP course.

“At the very minimum, students will be introduced to a wide range of ideas, individuals and social movements,” he said, “The current framework is solid work, but not everyone is going to be happy” — especially when “you get politics involved in higher education,” Canton added.

He pointed out that, at the high school level, instruction is going to be “very content-based,” but that there’s still space to create critical questions about issues such as poverty, inequality and segregation for students to think about.

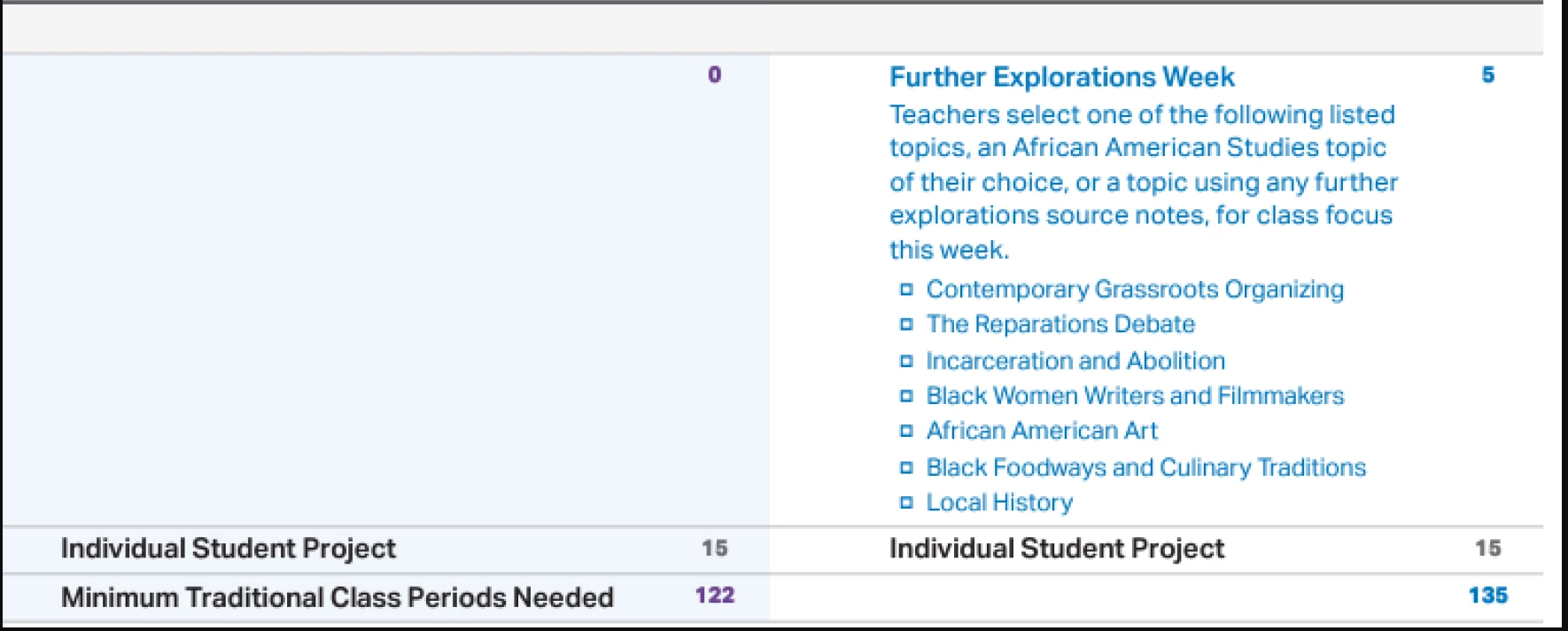

AP African American Studies course includes a week for further explorations of optional topics and a personal project that counts towards the final AP Exam. Courtesy of College Board

But, he admits, with current legislation that limits what teachers can say about systemic racism, that instruction can vary.

“Will you get a sanitized version, or will you get a nuanced critical version?” said Canton, “For K-12, that’s the ongoing debate: what are you going to teach students?”

Jessica Wright, a member of the Florida Freedom to Read Project and an educator involved with curriculum development, said the new AP African American Studies course is a “vast improvement” to the current state standards on African American history, but the framework can go further.

“There is some viewpoint censorship that exists as it relates to more modern topics,” said Wright, pointing to incidences of police brutality, including the deaths of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd, a catalyst of the Black Lives Matter Movement.

Wright noted that there is a mention of Colin Kaepernick, the NFL football player who kneeled in protest of police brutality.

“But when you look at the broader historical pieces that explain those systemic issues, they’re not there,” said Wright, “… and the problems, I would argue, that were created by colonialism and imperialism.”

The AP African American Studies course includes a week for further exploration of optional topics and a personal project that counts towards the final AP exam.

The College Board’s Latomia pointed out that students will still have the option to talk about issues not included in the formal framework through a personal project, which will count towards the AP exam taken at the end of the year. She said this option offers flexibility and opportunity for those contemporary topics.

The Black Lives Matter Movement is a topic area flagged as a “concern” by the state of Florida, said Canton. But he said it should be viewed and studied like other social movements critical to advancing civil rights.

“For a lot of young people, Gen Z-ers, this was a wake-up moment for political consciousness, just like for many in ’92 that was Rodney King, and in the late ’60s, that was when Dr. King got assassinated — a lot of young people organized on campus,” said Canton, “it’s been weaponized and demonized, but it’s nothing more than another social movement in the long history of American society.”