Both Viola Davis and Chadwick Boseman deserve Oscars for August Wilson’s critique on the human condition and race in America in ‘Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom’

BY DWIGHT BROWN, NNPA News Wire Film Critic

Who’s the Mother of the Blues? Better say Ma Rainey!

It’s a steamy Chicago summer, just like the rest. Hot. Humid. Even the streets are sweating. Ma (Viola Davis) comes up from Georgia to Chi-town to make an album. Her quartet arrives before she does, practicing in a cramped recording studio rehearsal room. It’s 1927.

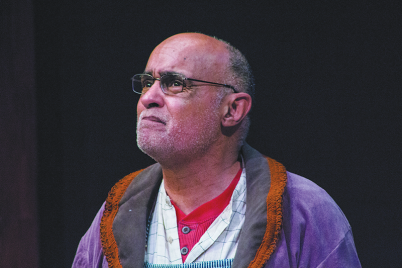

Cutler (Colman Domingo, If Beale Street Could Talk), the so-called bandleader, plays the trombone. Toledo (Glynn Turman, How to Get Away with Murder) tickles the ivories on the piano. Slow Drag (Michael Potts, The Wire) gives the band its rhythm with his upright bass. The over-ambitious Levee (Chadwick Boseman, Black Panther) blows his trumpet. The rest of Ma’s entourage includes her coquettish much younger lady friend Dussie Mae (Taylour Paige, Zola) while her 17-year-old nephew Sylvester (Dusan Brown, 42) drives her fancy car.

Cutler tries to wrangle the musicians, but Levee resists and wants to arrange some songs, his new way. The older and younger band members quarrel, arguing about the slightest things: Cutler, “I don’t criticize other people’s music.” Levee responding with pure insolence: “I do. I got talent.”

Things aren’t going much better in the studio office. Irvin (Jeremy Shamos, Birdman), Ma’s tactful manager, tries to appease everyone while they wait for Ma, who is really late and holding up the session. Sturdyvant (Jonny Coyne, The Blacklist), the impatient producer is concerned about the cost of studio time. As businesslike and determined as the two men may be, they know not to upset their prickly recording star. She’s a hard woman. Irvin to Ms. Rainey upon her arrival: “We’ll be ready to go in 15 minutes.” Ma, staring him down: “We’ll be ready to go when Madame says it’s ready to go.”

Angst, anger and rivalries intensify in the rehearsal room and recording studio, too. Adding to the drama, Levee can’t stop flirting with Dussie and if Ma finds out, wow! Couple the trumpeter’s arrogance with Ma’s stank attitude and easily someone may not survive the session. Will the album ever get recorded? If so, who will be its artistic director? The last one standing.

Playwright August Wilson was a master of relationships, contentiousness, frayed emotions and subplots on top of subplots. He deftly created rich characters who carried heaps of emotional baggage. Their thoughts were often disseminated in piqued dialogue, fervent interactions and outbursts brought on by personal strife or racism. The kinds of themes surrounding Black life that were also shown in the other nine plays in Wilson’s “American Century Cycle” series.

Equally telling of the times is the battle of wills between the self-confident Ma Rainey and her white manager and producer. It isn’t just about the tension inside; it was also about the racial friction out in the world. Blacks were being mistreated sometimes massacred in 1920s Chicago. As the producers try to steer Ma — baiting her with the accomplishments of her former protégé, Bessie Smith — she puts them in their place. What she wants goes down — the easy way or the hard way.

Wilson takes the essence of the self-empowered Ma Rainey, a real blues legend, surrounds her with fictional people and weaves a tale like a consummate storyteller. Actor (TV’s Billions) and writer (Lackawanna Blues) Ruben Santiago-Hudson adapts Wilson’s 1982 play and it’s hard to distinguish what is new and old, even if you saw the original Broadway show. The premise, characters and some settings are the same. If there are tweaks in the dialogue none will be obvious, even to the most discerning theater fan.

It’s the job of the screenwriter and film director George C. Wolfe (Lackawanna Blues) to make the source material cinematic. Not an easy task, but doable. Though there may be more sets and locations in this film version, many scenes are still stagey and dialogue heavy. Dangerous Liaisons, Amadeus and Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo & Juliet took the big leaps from play to film, using the moving image medium to its best. Films like Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf and Glengarry Glenn Ross didn’t, but were excellent anyway. Ma goes in that latter category.

Also, the original play featured singing, though it is not a traditional musical. Here, there are times when Davis appears to be lip-syncing, apparently to Maxayn Lewis’s vocal tracks. Then there are instances when she sings with her own voice. Post 2012’s Les Misérables and its authentic live recordings, all of Davis’ vocals should have been live. The band can get away with playing to a track, her Ma cannot—it’s distracting.

The camaraderie between the characters and actors seems effortless. They have the congeniality of a surrogate family. Also, conversely, the hostility and jealousy befitting a real warring clan. All that makes Levee’s acting out and threats particularly scary and dangerous.

Colman Domingo, Glynn Turman and Michael Potts are the glue, playing older guys set in their ways, acting civil and demanding respect in return. Boseman’s Levee is the unrestrained interloper exploiting opportunities, dismantling tradition and striking back at the world that hurt him. Boseman, with the agility of an extremely accomplished artist, acts both venomously ferocious and horrifically pained with equal conviction: “God ain’t never listened to a n—er’s prayers.”

Ma’s strength, as depicted by Davis, is her keen ability to dominate. Her Rainey is belligerent, fiery and explosive. As an unapologetic lesbian who owns her artistry and self-worth, she overpowers everyone. Getting in the face of a disrespectful cop, hammering Irvin and chugging a bottle of Coke like a longshoreman are indelible images.

The footage is a gorgeous spectacle: The color spectrum (golds, beiges, olives, purples) flatters brown skin. Natty costumes by Ann Roth (The English Patient) and vibrant production design by Mark Ricker (Trumbo) add verve. Exterior shots glisten through the lens of cinematographer Tobias Schliessler (Dreamgirls). The film flies by in 94 minutes thanks to Andrew Mondshein’s (The Sixth Sense) astute editing.

Looking for a happy go lucky film? This isn’t it. Hate the overuse of the “N” word? Beware. Otherwise, fans of adult dramas will be amazed even flabbergasted. In part due to August Wilson’s astute observations on the human condition and race in America. In part because Boseman and Davis deliver performances so incendiary that if they’d done them on stage they would have burnt the house down.

Released in select theaters on Nov. 25 and available on Netflix Dec. 18.

Visit NNPA News Wire Film Critic Dwight Brown at DwightBrownInk.com and BlackPressUSA.com.