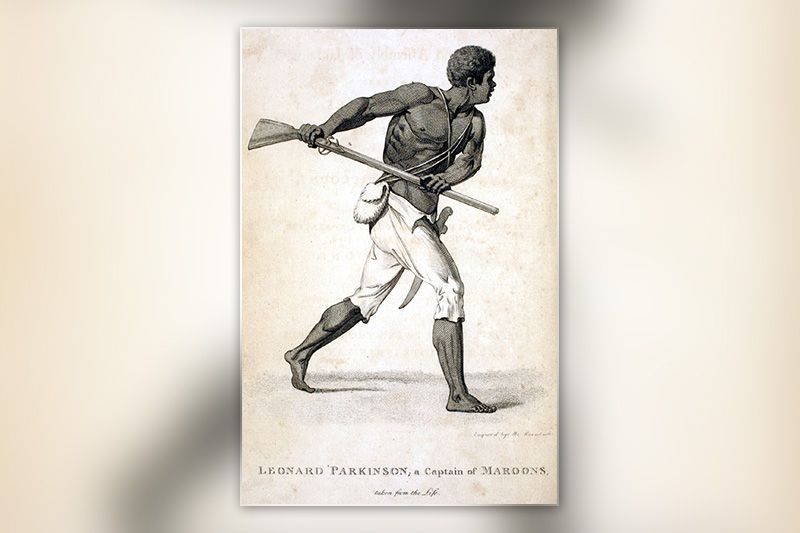

Leonard Parkinson, Maroon Leader, Jamaica, 1796

By Jacqueline Hubbard, Esq., ASALH, President

The English word “maroon” derives from the Spanish word cimarrón, which is based on an Arawakan root. Cimarrón initially referred to cattle that had escaped and living in the hills in Hispaniola. Soon the term referred to the enslaved indigenous population who escaped from the Spaniards on Caribbean islands.

By the mid-16th century, the word was used to refer to African runaways from enslavement in the Americas. Maroons could not bear to be enslaved, so they ran away and established their communities, often deep in the woods, swamps, and nearby hidden waterways. The word has continued to mean a type of fierceness, independence, wildness and the possession of an unbroken spirit.

In an essay featured in “Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619-2019,” historian Sylviane A. Diouf wrote that between 1700 and 1724, the many revolts, marronages and the more than 50 insurrections aboard slave ships posed a potential threat to the 13 British colonies.

During the Revolutionary War, the British often armed rebellious free, enslaved, and runaway Black men, trained them in military warfare, and taught them how to use the weapons of war. After the war, the ones who qualified to leave with the British did so. The ones that were left behind continued their rebelliousness by establishing maroon areas and resisting re-enslavement.

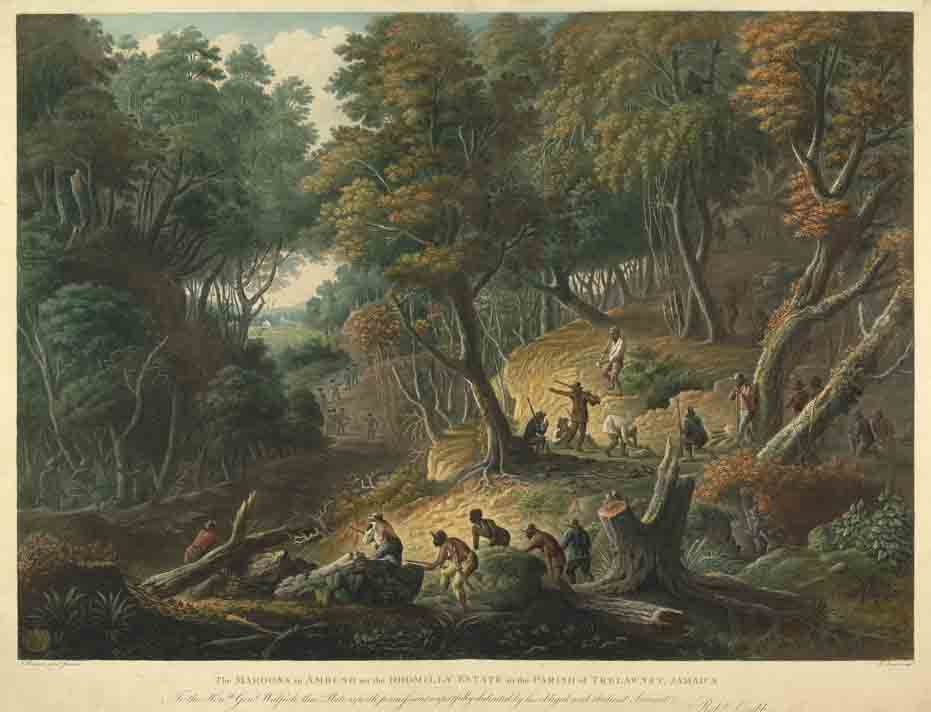

1810 aquatint of a maroon raid on the Dromilly estate, Jamaica.

After the maroon communities were established, women and children joined the runaways. Knowledge of the maroons is an essential part of African-American history. It has been written that during the Civil War after the Union Army began the active and open recruitment of Black troops, many men from maroon communities joined the Union Army and fought against the Confederacy.

Maroon colonies were established in the southern United States, South America and the Caribbean islands. In the United States, before the abolition of slavery, maroon communities existed in South Carolina, Virginia, North Carolina, Florida, Louisiana, Alabama and probably other southern states.

Historians generally agree the largest maroon colony in the United States was in the Great Dismal Swamp, on the border between Virginia and North Carolina. Other well-known maroon sites included the out islands of Georgia and South Carolina.

The maroons sought to ensure their freedom and maintain their African culture and beliefs. They came from different African tribes and often initially spoken diverse languages as they came together. They survived by developing, securing and creating for themselves ways of survival in the wilderness.

Maroons made or acquired necessary tools, shelter and weapons; they established small farms and developed ways to fish and hunt for food. The communities were self-governed, and for the most part, peace was maintained. Maroons found ways to safely trade with outsiders while keeping the location of their colonies a secret for as long as possible while taking in other runaways.

Betrayal or discovery by enslavers would lead to death and destruction of the maroon communities. When located, maroon colonies would be burned to the ground, and those who failed to escape would be tortured and killed.

Maroons posed the threat of insurrection to plantation owners because of their intense hatred for the institution of slavery. They were constantly on the alert to defend themselves from their potential enslavers. They lived as free people, beyond the sight, sound and control of the plantations.

Diouf, describe maroons as tenacious, creative, self-confident, fearless and resilient.

“They displayed all these qualities and more to their enslaved admirers. Maroons became folk heroes,” she wrote. “Maroons created an alternative to life in servitude, a free life in a slave society, a free life in a free state. Free Blacks and runaways were still subjected to white supremacy; only maroons were self-ruled.”

In Florida, Black Seminole towns were built by maroons who were allied with the indigenous Seminole tribe. Called “Black Seminoles,” these maroon colonies found refuge in central Florida swamps or hidden riverways.

Since at least 2005, local archeologists and anthropologists have been excavating a maroon site in Manatee County called “Angola.” Anthropologist Dr. Uzi Baram from New College of Florida and Dr. Sharon Howard, scholar and author, have been tirelessly working with local volunteers to bring that site the recognition it deserves.

The site was recently named a stop on the Underground Railroad by the National Park Service.

The public is welcome to view the site at the Manatee Mineral Springs Park in Bradenton.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.