“I appreciate the celebration. I appreciate the commemoration. But let’s not forget the reparation,” said J. Carl Devine, Ocoee Massacre descendant and St. Pete resident.

BY DEIRDRE O’LEARY and J.A. JONES, Staff Writers

ST. PETERSBURG — During the 2020 election cycle, much attention was paid to the growing voter suppression across the country. Last year’s election was also the 100-year-anniversary of what is still the largest U.S. incident of voting-suppression terrorism and violence ever – and it took place in Florida.

The country’s most harrowing and deadly act of targeted violence against Blacks attempting to cast their legal right to voted right happened right up I-4 in Orange County: The Ocoee Massacre.

Following the Reconstruction Era (1865 to 1877), many southern states passed laws that essentially disenfranchised Black voters. In turn, Black activists formed the “Union Leagues” and worked to register Blacks as Republicans, which as the party of Lincoln and Emancipation had (largely) affirmed voting rights for all citizens, white and Black. During the 1920 Republican National Convention, the party went as far as announcing opposition to the practice of lynching as part of their platform.

However, Dixiecrats – white-supremacist-minded Democrats – held total control in Florida. In Orlando, the Ku Klux Klan marched in Florida’s streets and wrote a letter to the area’s few Republican representatives declaring: “We shall always enjoy WHITE SUPREMACY in this country and he who interferes must face the consequences.”

Black activists conducting voter registration drives for a year before the Nov. 2, 1920, presidential election hoped to assist in breaking the one-party rule that Dixiecrats held. Also, since 1920 was the first year women — Black and white — were able to vote, it was a high-stakes election that heralded a challenge for the white men insistent on holding their power.

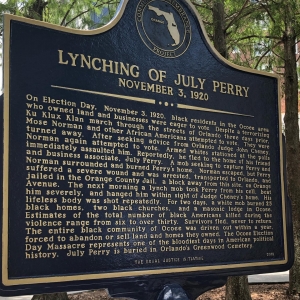

In Ocoee, Fla., an unincorporated town in Orange County, two Black men tried to vote on Election Day but were turned away. One was Mose Norman, a prosperous African-American farmer, who was turned away twice.

Norman sought refuge at the home of Julius “July” Perry, another prosperous Black citizen of the town. Both were powerful men in the area, owning vehicles, citrus groves, and between them, controlling a labor market of Black farmworkers.

A white mob surrounded Perry’s home, with two white men being killed as Perry drove the mob away with gunshots. Reinforcements were called in from Orlando and Orange County. Perry was eventually killed, and his body hanged from a light-post in Orlando to intimidate other Black people.

Norman disappeared and was later reported to have fled to New York. The homes, churches, and businesses of African Americans were burned to the ground, and up to 60 Blacks were killed. Blacks fled Ocoee, not to return for more than 50 years.

In 1920, Blacks owned several large parcels in Ocoee, including 25 acres owned by Perry. By 1930 there were no Black-owned properties in Ocoee and only “two servants” listed on the census for the area — out of the 255 Black residents listed on the 1920 rolls.

According to Orlando attorney Melissa Fussell, the land owned by the Black families was sold off, and along with Perry’s property, another 330 acres of land were taken from Black families. Since that time, descendants and their allies have attempted to gain reparations and restitution for their stolen property – which has an estimated worth of over $9 million today.

In 2019, Florida State Senator Randolph Bracy, who represents Ocoee, introduced a bill that would split $10 million among descendants of victims of the Ocoee massacre and require Florida schools to teach about the massacre.

Instead, a version of the bill was signed into law by Gov. Ron DeSantis in 2020 that removed the financial compensation for descendants but instituted statewide education on the event, slated to be put into the curriculum this year.

“This is the bloodiest day in American political history. Upwards of 50 people were killed,” said Bracy on WMNF last October. “During this time, in the early 1920s, 14 percent of the southern landowners were Black. After slavery, you had a generation of people who were acquiring land, who had farming skills, who were doing well.

“That is why you had these acts of terror. They were targeting these Black people’s land. You see a lot of wealth transference during this time. It was government-supported terrorism, allowing for land theft, the courts allowing the land to shift to those who were terrorizing Blacks.”

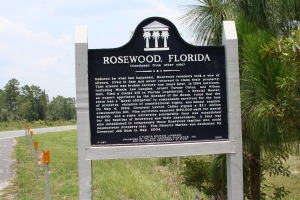

Bracy is hopeful that as legislators learn about the incident, reparations will return to the table. The descendants of the Rosewood Massacre received $7 million in reparations in 1994, the only time a state government made such payments.

In 2020, Orange County revealed a marker and declared Nov. 2 “Descendants of the Ocoee Massacre: Honoring Their Ancestors Day.”

At the ceremony, St. Pete resident J. Carl Devine, the grandson of Ocoee residents who fled their land, John and Roxie Williams, reflected on the tribute.

“Most of my life, growing up, I heard about Ocoee. They never got over the fact that people ran them off their property and took their land from them,” said Devine. “I appreciate the celebration. I appreciate the commemoration. But let’s not forget the reparation.”

Today, Devine and other descendants are still attempting to get rightful financial compensation for the loss of freedom, land and the decades of emotional and psychological trauma the event leveled on descendants of the tragedy. After many years of fighting, he now believes that legal action is the only way forward.

“These people know that they did all of this, they have known this for years and years and years — and they keep fighting the truth and reality. I just believe that they don’t want to do the right thing,” said Devine in a recent conversation.

He also believes that Rosewood gained more attention than Ocoee had to do with the cause of the massacre.

“Rosewood was about sex and Black men and white women, and they made a big issue of that. Ocoee was about Black people voting — totally different.”

Devine feels that white America’s fascination and fear around their belief that “every Black man wants a white woman” allowed them to focus more on that incident than the Ocoee occurrence.

“One was about a lie, and the other was about Black people voting. And it’s very similar to what we’re going through right now.”