Dominique Cobb had two relatives buried in the Zion Cemetery, the first African-American cemetery in Tampa.

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (found beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Dominique Cobb was always intrigued with the story of Zion Cemetery, the first African-American cemetery in Tampa. While visiting family one day three years ago, she found herself face to face with the human aspect of this history.

“I actually have a family member — two family members — that live right there on the grounds,” said Cobb, who sits on the Historic Preservation Commission in Tampa. “You literally walk out of their door, and you see the sign with the names. I was actually leaving her house, dropping her off some food, and I came out her door, and I was like, ‘Oh my goodness! This is the exact location!’ And seeing those names and seeing babies’ names…seeing it made me say, ‘Hey, I’m looking at the names, so I know someone is there.'”

The segregated-era burial ground is located on the Robles Park property and was created in 1901 by Richard Doby, a Black businessman who sold it a few years later. By the 1920s, Zion was owned by white businessmen who parceled it out for development after they reported the bodies had been removed.

During the construction of public housing development Robles Park Village in 1951, construction crews dug up coffins with human remains. As late as 2019, archeologists confirmed via ground-penetrating radar that caskets were still beneath the ground, under public housing, warehouses and a tow lot along Florida Avenue.

Cobb said her relative, Ms. Howard, has relocated and wasn’t aware of her proximity to the erased cemetery. There have been meetings for eventually repurposing or rebuilding Robles Park. Cobb believes more could have been done for the residents following the 2019 investigation into the cemetery that revealed bodies were still there.

“I feel as though there should have been more wraparound service for those who actually have to see it,” she said. “Like I said, leaving out her door, seeing names, not knowing what they’re actually connected to — that’s a mental aspect that I don’t believe was grasped. I know that took a toll on her and other families that constantly have to see that.”

Cobb comes from a long line of Tampa residents, including vegetable farmers and longshoremen, and her great-grandfather literally helped build the city as he laid bricks along Nebraska Avenue. She recalled her youthful days at Robles Park, where she would play Sunday kickball games and walk her dog near the pond. The predominately Black housing complex has been there as long as she can remember.

“We enjoyed the whole neighborhood; it was very walkable then,” she said. “It was safe in my time.”

Cobb said that the local NAACP is working with the Tampa Housing Authority to help facilitate the relocation process for residents.

Concerning the African American Burial Ground Oral History Project, Cobb said one thing that comes directly to mind: “Don’t let them forget me!”

“One thing that I believe [about] our culture that tends to happen is we forget our ancestors, and we have a complete site, a whole cemetery of people that may be connected to me, may be connected to you … I need them not to be forgotten.”

Cobb would like to see that land marked with something peaceful, as it is sacred ground and commemorates a resting place.

“Being able to have a place to go to and say, ‘Let me sit here. I may not have known them, but let me read about them, let me see some of the stories of the people who lived here,'” she said.

When she worked with the Tampa Housing Authority, Cobb said it held a memorial celebration during which people read the names of those who were buried there.

“That kind of hit home for me because hearing last names that are similar to mine, hearing about a mother and twins who died during childbirth … knowing that my people, possibly my people are here, I want to make sure that they are not forgotten,” she said.

There are other historic African-American cemeteries in Tampa that Cobb wants to ensure are not forgotten.

“I believe that we can definitely right this wrong,” she said. “There is no way that a home is built on someone’s final home. Yes, acknowledge that, but how do we correct that?”

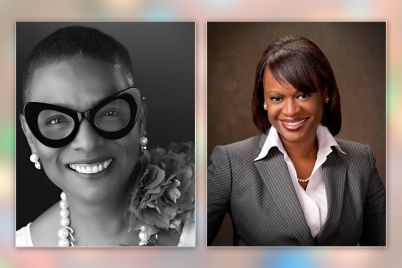

Dr. Antionette Jackson interviewed Dominique Cobb on Sept. 19, 2021.