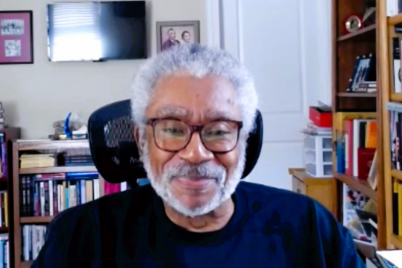

Joseph C. Myrick’s family was one of many affected by the displaced Black cemeteries in Pinellas County over the years.

BY FRANK DROUZAS, Staff Writer

CLEARWATER — The African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project is an ongoing USF research study that addresses the erasure of historic Black cemeteries in the Tampa Bay area. Awarded a USF Blackness and Anti-Black Racism grant in 2020, it consists of faculty, staff, and students from multiple disciplines across USF St. Pete and Tampa campuses.

The project focuses on activities to identify, interpret, preserve, record, and memorialize previously unmarked, erased, abandoned, and underfunded African-American burial grounds in Florida, with a focus on Tampa’s Zion Cemetery (located beneath Robles Park Village) and St. Petersburg’s Oaklawn, Evergreen and Moffett cemeteries (found beneath a Tropicana Field parking lot and I-275).

One aspect of the African American Burial Ground & Remembering Project (AABGP) is recording oral histories of those who remember or are related to those lost to time.

Joseph C. Myrick’s family was one of many affected by the displaced Black cemeteries in Pinellas County over the years. Myrick, born in Clearwater in 1968, is the son of Audrey Nee Dixon and Joseph Myrick Jr. When “60 Minutes” aired its segment on the Greenwood Cemetery in Clearwater a few years ago, it hit home for Myrick as it featured a photo of his great aunts and uncles.

“I was very touched by the photo that was highlighted in that “60 Minutes” video at the very end of the Mack Dixon family,” he said. “[The] photo that has circulated throughout my family for about 10 years. So, when I saw it, I knew it was legitimate.”

Myrick is a supervisory United States Probation Officer working for the United States district courts and lives in Ocala. He thought it was important to share this history with his colleagues.

“Because of my position with the federal government, we do a lot of outreach into communities,” he explained. “But I wanted to share that video with my executive team.”

He showed the video to his chief probation officer and his four deputies to give them a snapshot of the Black history of Clearwater because a lot of their retreats and conferences happen on Clearwater Beach.

“And a lot of my colleagues, especially my younger colleagues, have no clue of the history when it comes to African Americans and Blacks and how that area was built and settled.”

Myrick said he began digging into the history, asking his older relatives questions concerning those days decades ago when these cemeteries were being uprooted or built over.

“They actually lived through that time,” he said. “And it was something with the cemetery; it’s something we all knew, but we never talked about it for whatever reason. I wish I knew the answer to it. I mean, growing up, I did hear some rumblings through the older aunts and uncles talking about it, but there was never no follow up from myself.”

Myrick explained that Greenwood Cemetery was located in a spot then called the Heights, near Cleveland Street and Missouri Avenue in Clearwater. His great-great-grandfather, Mack Dixon, Sr., purchased the original land for the cemetery.

“He had the property,” Myrick said. “He bought the property from between Cleveland and Court Streets and from Missouri to Greenville Avenue. And my aunt Brenda … told me that he donated — and he being Mack Dixon, Sr. — donated land to other churches in the area to bury their dead.”

Myrick said the cemetery land was taken from his uncle, and to this day, he doesn’t know the details of any transaction. His elderly aunt Brenda Buie couldn’t provide insight, either.

“I was speaking with Brenda and getting the background information,” he explained. “She made the comment, ‘They took the land.’ You know, so we can only imagine who ‘they’ might have been. The land was taken from my grandfather. We don’t know how or whether or not he signed a promissory note; he was swindled — we don’t know.”

Myrick’s uncle Bernard Dixon — Mack Dixon Sr.’s grandson — and Myrick’s older cousins are working with the NAACP to find out more, he said.

When Myrick’s older relatives attended high school in those days, they went to Pinellas High School before desegregation. After desegregation, they were bused to Clearwater High and other local schools. TR Dallas Funeral and Cremation Services handled arrangements for most of Myrick’s relatives when they passed.

“I think that a majority of my older aunts and uncles who were eulogized in Baptists CME, I think the funeral home that handled their bodies was Dallas Funeral Home,” he said.

Myrick pointed out that he and his cousins didn’t experience the same prejudice or “restrictions on our movements” in the Greenwood area as his older relatives.

He primarily grew up in St. Pete but spent many weekends at his grandfather’s house in Clearwater. However, as a child, he spent his time riding bikes, playing sandlot football and baseball and not learning the family’s history.

His parents met at Gibbs Junior College, where his father played baseball and basketball. They eventually married and settled in St. Pete, off 34th Street and Queensboro Avenue. The house his grandfather lived located in Clearwater was located on Brownell Street. He recalls the close-knit community.

“Everybody knew each other,” he said. “And we would play with the kids across the street next door, you know, that lived on the street. I just have fond memories, just having, you know, Sundays after church, just changing my clothes into my play clothes and just going out there and seeing my friends who I hadn’t seen in the week…

As Myrick spent his youth in St. Pete, he recalled the various sections of the city, specifically Black neighborhoods such as the Gas Plant district.

“What’s interesting is that growing up, Central Avenue was an area that we were told that we couldn’t go around because you could pretty much get anything you wanted on Central Avenue,” he remembered. “When I was growing up, that was the red-light district, so to speak.”

Myrick does remember Webb’s City and shopping there with his mother. He remembers the Black neighborhoods and Black businesses where Tropicana Field sits now.

“I was too young to understand what was happening and how that property was eventually taken over by the city, maybe by eminent domain.”

He recalled the construction of Tropicana Field and the resulting migration of people from the neighborhood.

“I do remember, just a little talk about people moving, being displaced or being relocated to the other housing complexes in the area,” Myrick said.

As for displacement of the deceased, Myrick said he, his siblings and cousins were led to believe that his relatives may have been moved from Greenwood Cemetery, but he isn’t certain.

“My grandfather, Mack Dixon, Jr, purchased several burial sites at another cemetery,” he said. “That those relatives supposedly were moved; however, we don’t think they were moved. And if they were moved, it was only a couple of them, not all of them.

Myrick’s uncle Bernard said that the headstones were removed, which led them to believe that because the headstones were gone, the bodies were relocated. But his uncle is not 100 percent sure.

There should be a memorial placed at the site of the old cemetery, where the FrankCrum building currently sits, Myrick said, in the way of acknowledgment. He praised groups like the Black Cemetery Network and the African American Burial Ground Project that work with families associated with such cemeteries and strive to get the information out as part of the public record.

“I will say that accountability and acknowledgment of a wrong that was done to the Black community during that time,” he said. “And that there is some sort of retribution in the form of maybe a memorial site, actually tearing the parking lot up and moving the bodies.”

Dr. Antionette Jackson interviewed Joseph C. Myrick on Feb. 23, 2023.