On Feb. 23, the Community Remembrance Project Coalition and the Equal Justice Initiative unveiled the John Evans Lynching Memorial on Second Avenue and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Street. Evans was brutally lynched and shot on Nov. 12, 1914. Photo courtesy of the City of St. Pete.

BY NICOLE SLAUGHTER GRAHAM, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — On the morning of Nov. 11, 1914, St. Petersburg residents awoke to the headline: “Slain as he slept by unknown Negro” in the Evening Independent newspaper. Edward Sherman, who employed 11 African-American workers to clear land, was found dead by his wife, Mary. She had been assaulted with a pipe and possibly sexually assaulted — or at least this was implied in the newspaper coverage of the day.

John Evans, a Dunnellon, Fla., resident, was arrested and taken to the hospital where Mary Sherman was recuperating for identification. She could not identify Evans, and he was released and then later arrested again.

The next night on Nov. 12, 1914, Evans was broken out of jail, marched down to Second Avenue and Ninth Street South from where the St. Petersburg Jail was located on Fourth Street and Second Avenue South.

He was lynched by a crazed white mob of about 1,500 people for a crime he most likely did not commit. In fact, looking at the crime scene and the actions of Sherman’s wife, she either pulled the trigger herself or had someone do it for her.

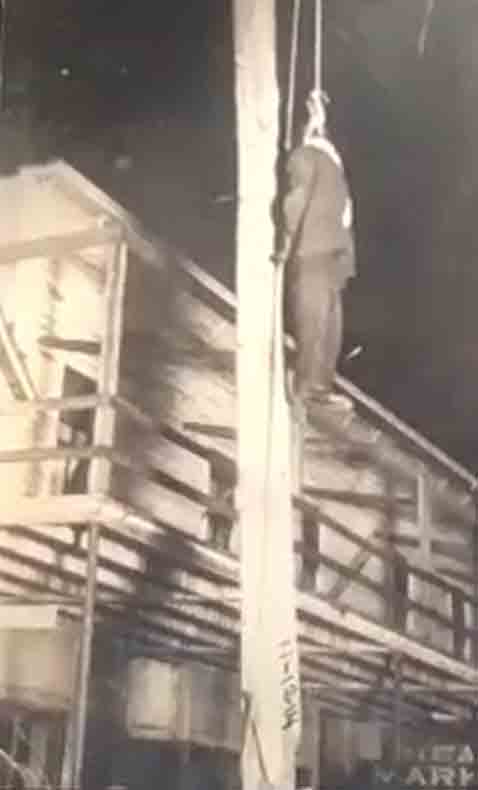

A postcard was made of John Evans hanging from a utility pole on Nov. 12, 1914.

Evans was hanged from a utility pole. Trying to survive, he braced himself on the pole with his legs wrapped around it. As he struggled to hold himself aloft, a white woman shot him from her car, inciting the crowd to fire upon him for more than 10 minutes.

White mobs then terrorized the black community for days in search of an alleged accomplice, Ebenezer Tobin. At least 170 Black residents fled their homes for safety. Tobin was later found and tried by an all-white jury, becoming the first person legally hanged in Pinellas County in Oct. of 1915.

No one was held accountable for Mr. Evans’ lynching due to the impunity granted by the racial hierarchy in St. Petersburg.

Fast forward to Feb. 23 of this year in the same spot Evans’ life was brutally cut short, a small, masked crowd gathered in somber remembrance at the unveiling of St. Petersburg’s first lynching memorial.

The marker acknowledges the city’s racist past and horrific acts against Black people, providing the story of Evans’ lynching on one side and a brief history of racial terror lynching in America on the other.

“Racial terror has always been about ensuring white supremacy,” stated Mayor Rick Kriseman. As leaders working together to build a city where there is opportunity for all, we must call out inequity, bigotry, hatred and racism whenever and wherever we see it. Before we can move forward, we must shine a light on the sins of our past.”

Senator Darryl Rouson

Among the event’s several speakers was Senator Darryl Rouson, who asked, “How do you welcome people to the site of tragic horror? How do you welcome people to the site of a tragic murder? How do you welcome people to a stark example of man’s inhumanity to man?”

The answer, Rouson said, was not by celebrating the death of Evans but by welcoming the beginning of reconciliation.

“You welcome people to the beginning of healing by memorializing the restless spirit of John Evans.”

Rouson’s remarks echo the goal of Pinellas Remembers and the Equal Justice Initiative – the two organizations that spearheaded the project.

Community Remembrance Project Coalition co-chair Gwendolyn Reese said the purpose of the memorial was much more than erecting a marker. Instead, she hopes the marker will serve as a starting point for open, honest discussions about racism and lynching.

“Racial terror has always been about ensuring white supremacy,” said Mayor Rick Kriseman.

These honest conversations, she said, were the jumping-off place for community healing to begin.

Community Remembrance Project Coalition Co-chair Jacqueline Hubbard recounted the known events that led up to Evans’ murder and the specifics of the horrific way he was slain.

“Let us bring something positive out of their deaths,” she said, referring to the more than 6,400 Black bodies that swung from trees and makeshift gallows between the period of Reconstruction and the initial part of the Civil Rights Movement in the early 50s.

“First by remembering that it happened; two by accepting the fact of it happening; three by agreeing that it will never happen again,” she asserted.

Rev. Pierre Williams was able to humanize Evans, stating that he was his grandfather’s, Loomis Williams, protégée.

Rev. Pierre Williams was able to humanize Evans, stating that he was his grandfather’s, Loomis Williams, protégée. Evans was a handyman, a “noble” figure that often visited Methodist Town, then-St. Petersburg’s second-largest Black community.

“He was a man who gave food to the poor, money to the poor, greetings to the poor. That is John Evans,” Williams said, adding that he promised his father never to forget Evans’ story.

Mayor Kriseman expressed gratitude for all of the partners who made the memorial possible, including the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg and the Tampa Bay Rays Foundation, both of which had a hand in funding and bringing awareness to the memorial.

Brian Auld, president of the Tampa Bay Rays, admitted that although he knows a lot about St. Petersburg’s history, he was unaware of the city’s racist past.

Brian Auld, president of the Tampa Bay Rays, admitted he was unaware of the city’s racist past.

“I’m embarrassed to say that until a few years ago, I didn’t know there was anything more to the green benches than an homage to a senior community or the name of a local brewery,” he confessed. “We cannot turn a blind eye; we cannot sweep it under the rug, we can’t ignore it, we can’t just move on and leave it in the past.”

Invoking the long-standing African and African-American tradition of poetry, Deputy Mayor Dr. Kanika Tomalin provided her remarks in iambic pentameter, a style of verse made most popular by Shakespeare.

She referenced the horrors faced by Black communities in the past and in the present and asked the audience to think about their roles in such terrors. She also acknowledged the power of the lynching memorial and the power of looking at and understanding history.

John Evans’ lynching memorial serves as a starting place for healing in a city whose past is filled with racial injustice. It provides much-needed acknowledgment of past wrongs and allows the community to move forward.

Historical facts were provided by journalist Jon Wilson and Jane McNeil’s Community Conversation sponsored by Tombolo Books.