November’s Community Conversations titled ‘Our Stories Matter: Memories of the Gas Plant District’ on Nov. 15 at Tombolo Books highlighted residents’ stories of growing up in the historic neighborhood. Top row: Gwendolyn Reese, Mary Murph, Carlo Lovett, Thomas ‘Jet’ Jackson; bottom row: Wanda Stuart, Shirley Smith-Hayes, George Stovall, Andrew Walker.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — The African American Heritage Association’s (AAHA) November Community Conversations spotlighted former residents of the Gas Plant District. Held at Tombolo Books, the public discussion allowed residents to share stories and talk about the neighborhood that meant so much to them.

For too long, AAHA President Gwendolyn Reese noted, the outside media had depicted it in a negative light.

In 1910, Davis Academy, later to become Davis Elementary, opened as the first formal school for African Americans and was located in the Gas Plant neighborhood. [City of St. Petersburg]

Shirley Smith-Hayes, who lived in various places around the area, recalled that near the Royal Court Apartment (Laurel Park) on 16th Street South, there was a cemetery.

The impact of Laurel Park’s demolition, once known as Royal Court Apartments, was socially and economically devasting. Not only were residents forced to leave their homes, the jobs and affordable housing promised to the Black community never materialized. [Tampa Bay Times]

Her family then moved to Fourth Avenue, across from John Baker’s saloon, which provided free Friday entertainment for her and other young kids as they sat on their porches and “listened and looked,” Hayes mused.

“I never saw the blight. I never saw what the newspaper said,” Hayes stated. “Maybe it was there, and I just didn’t see it, but people actually slept on their porches in the summertime when it was hot. So, you know you felt safe … I have really good memories of the neighborhood.”

Bethel Metropolitan Baptist Church was displaced after the Gas Plant District’s destruction. [City of St. Petersburg]

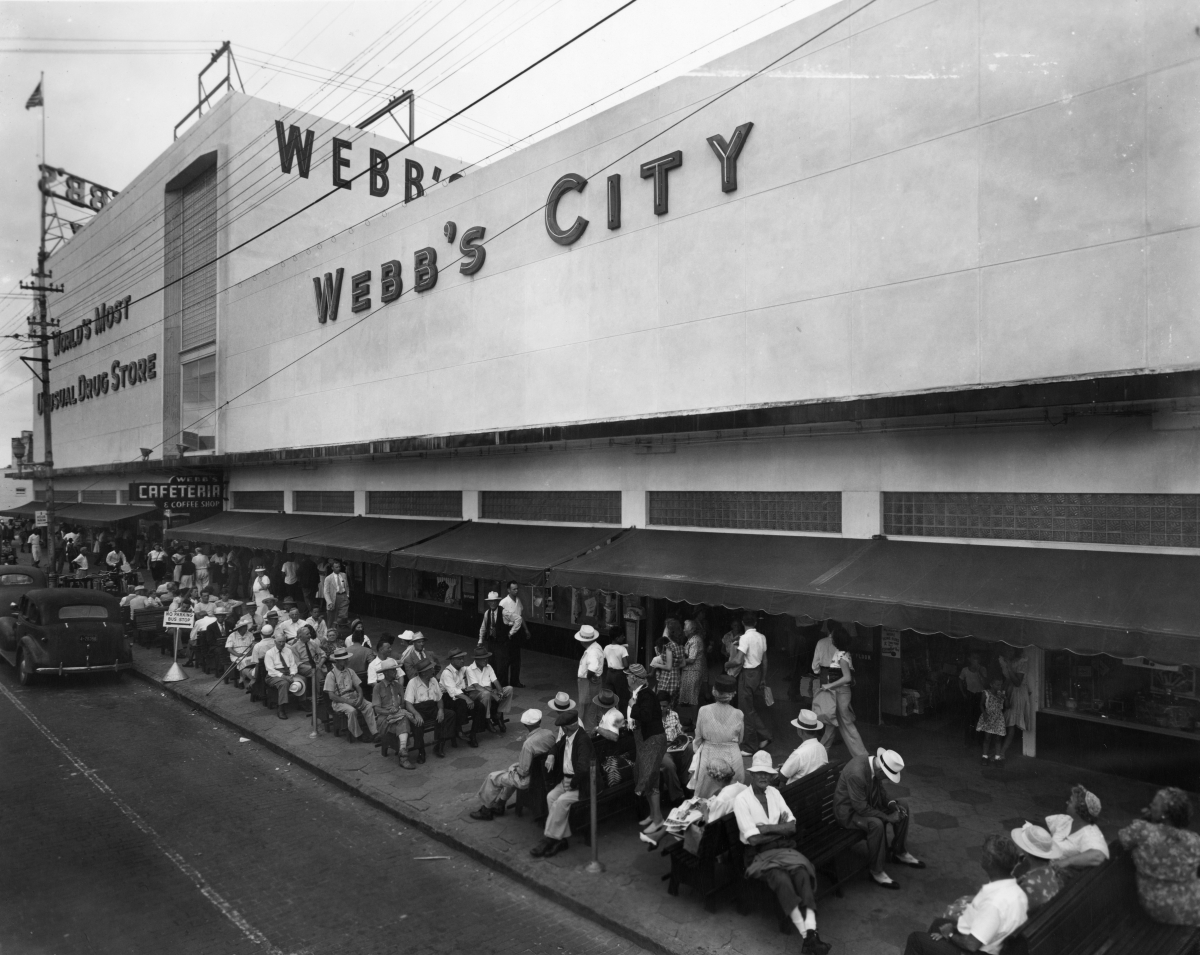

“There were so many businesses — I mean Black businesses — along that strip, between First Avenue, Second Avenue and Third Avenue. We had grocery stores – Webb’s City was one of the most popular stores,” he recalled, adding that you could get 10-cent chicken wings there.

It was a community, he went on, where everyone looked out for one another, and residents didn’t have to lock their doors at night. The teachers motivated the students to do their best, and the coaches at the high school were like “fathers to us,” he recounted, noting that some young athletes from the area went on to play professional sports.

Mary Murph recalled some residents of note, including Dr. James Maxie Ponder, the first African-American doctor to practice at Mercy Hospital. The doctor rented rooms in his home to teachers who taught at 16th Street Junior High.

Murph’s uncle owned a gas station, and she worked in the store next door. As the teachers walked from Ponder’s house to the school, she got to talk to them and know them very well. One teacher got Murph to join the school chorus.

She sold cookies and candy and ran the cash register. She made two dollars a week, a dollar and a half for her school lunch, and 50 cents for mad money, which she saved.

Her uncle also had a baseball team that played at Campbell Park, and Murph sold concessions, where she also earned and saved money, “learning the value of a dollar.”

Andrew Walker recalled his days as a youngster when he used to walk by the McRae Funeral Home. Eventually, he’d stop to talk to owner Mary McRae, who’d give young Walker a Coke.

“One for her and one for me, and we would sit on the bench and talk,” he said.

Another recollection for him was Gibbs High teacher Ernest Ponder’s daughter, Erna, to which he took a liking and noted that at their residence, “there was a wall that I was standing on to get a kiss! I was a little boy, but she was probably 18 or 16! And then her father would come and try to box with me!”

Though very young, Walker recalled the sanitation strike led by Joseph Savage coming to the neighborhood, with people marching and holding signs with messages like “We Are Men” and “We Deserve Fair Pay.” The sanitation strike was an integral part of the Civil Rights Movement, and Dr. Martin Luther King’s brother, A.D. King, marched down St. Pete’s streets to support the striking sanitation workers.

Walker worked a summer job cutting grass at Lincoln Cemetery and at McRae Funeral Home, where he started by washing cars but eventually took on more responsibility, like driving families to funerals and picking up bodies from Bayfront Medical and even Tampa.

Such job experience, exposure to opportunity and conversation was a form of mentoring, Reese pointed out, and “that’s what we had in our neighborhood, whether you walked to school with your teacher, or the teachers chatted with you…we had our role models living right next door to us.”

“Think about the opportunities that we knew were available to us because we saw it every day,” Reese asserted, adding that she lived between two doctors and walked to Junior High with the librarian.

Because of the staunch segregation at the time, African Americans, no matter their income, all had to live together, Reese pointed out. Two-story homes and bungalows next to low-rent apartment buildings were not uncommon.

Wanda Stuart lived at 330 18th St. S, on the current Tropicana Field parking lot grounds. The unique thing about living there was that it was a “corner house” that her grandmother had bought. When the construction on the interstate began, city officials only wanted “the front porch of my grandmother’s house.”

“They said, ‘You can take what money you can get off this front porch, and you can stay here,” Stuart said. “She had already paid off her home and all of that.”

Stuart’s grandmother, displaying business acumen though only possessing a high school education, then decided to rent her house out and purchase another property on the other side of town. When the city needed more land to develop, she eventually settled at 1304 Fifth Ave. S, where she was neighbors with Walker’s father, Mordecai.

Some 500 households, nine churches and 30 businesses were razed to make room for a baseball stadium without a team. [Tampa Bay Times]

“There were three moves before we finally landed,” she recalled, “and that was quite stressful on my grandmother.”

A sense of community was something that Stuart underscored, noting that the people sitting next to her were “from different walks of life, and our lives have been impacted by the community that was called the Gas Plant.” She recalled, as a young girl, picking up fresh vegetables with her grandmother — who worked as a cafeteria manager at Gibbs High — and watching her grandmother and other women “make the best fresh food [for] the Gibbs High School students and football teams and basketball teams — those were the days!”

Carlos Lovett, who lived at 1218 First Ave. S, was 15 when his family had to move, and his family was one of the last families remaining in the area. He recalled the shift from a bustling, close-knit community to a deserted, run-down neighborhood.

“It was just like a ghost town,” he said. “It went from a place where you felt safe, that you felt a connection, the only place that I knew … being right off of First Avenue, we would see the parade set-ups; we would see the circus, we would see the train bringing in the circus animals because we couldn’t afford the circus.”

Bordered to the west by the gas cylinders and to the east by Webb’s City, the Gas Plant neighborhood was home to several Black churches, businesses, and homes. African Americans made up the bulk of the shoppers at Webb’s City but were not permitted to eat at the lunch counter or shop in the ‘ready to wear’ or ‘men’s suits’ departments. [State Archives of Florida]

“I have had dogs sicced on me because I had missed a train,” he said.

Lovett, one of 11 children, reiterated the sense of family that many residents shared, explaining that “even if we weren’t family, we were families,” and recalled a sense of loss when he had to leave.

“I kind of lost a lot when I lost the Gas Plant neighborhood,” he said, “because up till then, my family had been there so long. It was my playground.”

He recalled swimming in the nearby creek and playing along the bridge, and when the gas plant tanks themselves were being dismantled to make way for progress piece by piece, Lovett said, “It’s just like a piece of yourself getting taken away.”

Some residents wound up homeless, Reese pointed out, after the development projects began.

“If you owned property, you were compensated somewhat, but if you rented, you were not,” she said, “and when you moved to other places, the rent was so much higher than where it was in the Gas Plant area that many people could not survive.”

That is what happened to Lovett’s family. His family moved a lot, many times staying with family.

“I would come home one day from school, and all of our furniture would be out. This happened so much,” said Lovett.

From 1906 to 1986, African Americans suffered at least 10 displacements from the Gas Plant and adjacent Peppertown neighborhoods. These incidents forced the relocation of hundreds of Black households in groups ranging from 10 to 500 households at a time. [Tampa Bay Times]

“I would take 25, sometimes 50 pounds of ice into the kitchen,” he recalled, “and I got to know the families. I got to know those families as mothers and fathers and children and grandparents. I got to know them really well. I knew their names, and they knew my name.”

Stovall lived on Arlington Avenue and 11th Street, walking distance to the main ice plant, where his father had his office. One day, a young Stovall asked his father about a sign hanging in the plant.

“I said, ‘Dad, why do we have a “whites only” drinking fountain?'” he said, adding that many of the employees were African American.

His father only laughed, nudged Stovall on the shoulder, and walked away. So that’s that, Stovall recalled thinking. Yet in a week’s time, that sign disappeared from the plant.

By 1986, the Gas Plant neighborhood was destroyed to make way for the construction of a baseball stadium instead.

“There was a brand-new drinking fountain, and everybody could use it,” he recalled. “I couldn’t believe it! So, when I went back to plant number two, I took down that ‘whites only’ sign myself!”

Stovall’s family then moved to Snell Isle, a sundown neighborhood at the time — all Black people had to be out of the neighborhood by sundown. Stovall said this reality upset his father, who employed Lily Chambliss, a Black nanny for his children. So, he built Stovall’s sister a life-sized dollhouse in the sideyard that could accommodate three or four people, complete with air conditioner, electricity, and television.

“That’s where Lily lived,” Stovall said, adding that she stayed during the week but returned on weekends to her place in her own neighborhood. “She lived on Snell Isle and didn’t have to be gone at sundown. She lived there!”

These former Gas Plant residents credit their upbringing in the historic neighborhood for their prosperous lives and careers.

Gwendolyn Reese was brought in as a consultant to the Gas Plant Redevelopment Project to ensure the community has a voice. [City of St. Petersburg]

She is proud to be the first griot, or African storyteller, for the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg.

“Our stories are so important. They are beautiful and messy, but they are important and must be told,” Reese stated. “I’m living my dream of telling our stories, making sure they are told by us, to us, and to others to educate people about our presence, our contribution, who we are, and what we’ve done to make this nation what it is.”

Walker, the health and well-being director at the National Senior Games Association, developed a health-conscience lifestyle and credits his grandfather — a World War I vet — for instilling the importance of exercise in him. He became interested in anatomy and physiology from working at McRae Funeral Home.

Stuart is a drug prevention counselor who moved back to the area in 1991 and found that things were not like they were when she left.

“The work that I do is to help a community be all it can be through education,” she said, adding that she benefited by growing up around a family of educators.

Stovall went on to become a chiropractor and explained that one key to his success was being able to relate to and know “all kinds of different people.”

Murph was inspired by her teachers and participated in sit-ins on Central Avenue during the Civil Rights Era. She became an educator for 32 years.

Hayes, who helped her mother clean houses on Snell Isle as a pre-teen, decided that it was not the future she wanted and, after eventually attending Gibbs Junior College, became the first African-American female insurance adjustor in the state.

Jackson credits a group of ladies from his neighborhood who gave him a job as a youngster at their store and encouraged him to go to college. He attended Gibbs Junior College and worked for the city for 56 years.

Lovett works with special needs children for the school system. He does trauma-informed work and is starting a trauma coaching organization.

Editor’s Note: Gwendolyn Reese has a column called “I AM” in The Weekly Challenger newspaper, illuminating African-American history in St. Petersburg. If you see her on your travels, please tell her you miss her articles and to please start writing again.

Thank you for the article and the photos. It brings back memories, good ones. I loved my neighborhoods and my neighbors