On Dec. 29, 1966, Joseph Waller – now known as Omali Yeshitela — stripped the mural from the wall as he was leaving the building. He was arrested and charged with felony theft and spent at least 22 months in prison.

By Gwendolyn Reese

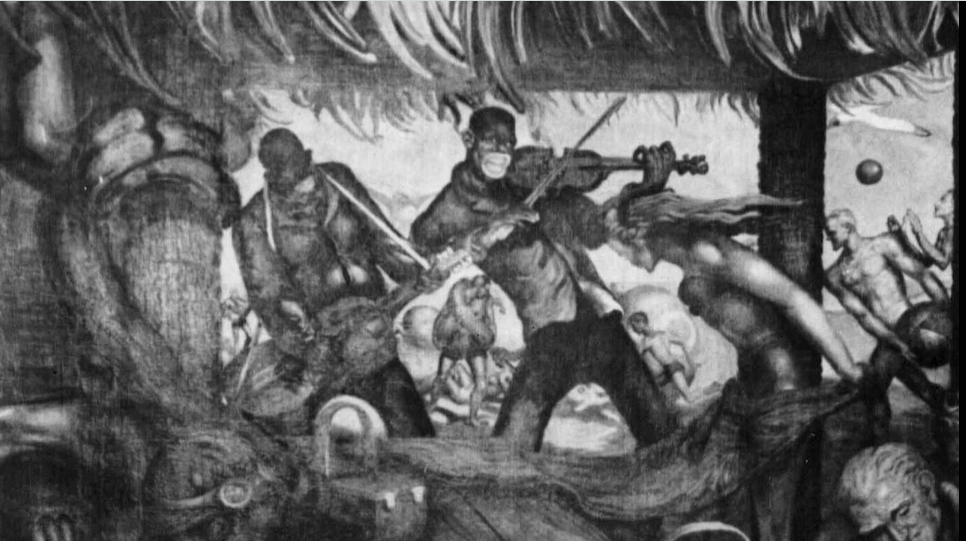

In 1940, George Snow Hill, painter and muralist for the Federal Art Project, a New Deal program, was commissioned by the federal government and the City of St. Petersburg for two 7 x 10 feet murals to be hung in the grand staircase in city hall. Hill’s Depression-era Works Progress Administration art is noted by some to provide a community record.

Working mostly during the New Deal era, Hill was commissioned to paint five murals for the Pinellas County Courthouse (some of which were considered indecent and even lewd because they depicted women in swimsuits). His other murals can be found at the Bayboro Harbor Coast Guard station, airports, and several post offices throughout Florida and Alabama, including one painted for the 1933 Chicago’s World’s Fair (later hung at the Florida Capitol).

According to a March 25, 1945, article in the St. Petersburg Times, Hill had been commissioned to paint murals featuring scenes of contemporary St. Petersburg, scheduled to be placed in city hall. One of the murals was a scene at the Million Dollar Pier and the other a scene of black troubadours (musicians) entertaining white picnickers at the beach.

The mural of the picnic scene was a caricature of black musicians depicting them as happy-go-lucky, with huge pink lips, and strumming banjos. The mural, which also included watermelons, was considered by many in the black community as denigrating and racist in nature.

The mural of the picnic scene was a caricature of black musicians depicting them as happy-go-lucky, with huge pink lips, and strumming banjos.

More than 20 years later, on Dec. 15, 1966, the Times printed the article “Negro Group Finds Mural Despicable.” The article reports a letter sent to Mayor Herman Goldner by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee asking for the mural to be removed or changed.

Goldner’s response was, “I must admit that I have looked at this mural for the past 10 years with nothing but admiration. I find nothing offensive in the portrayal of the troubadours and picnickers at Pass-a-Grill Beach.” He went on to say, “I think that all minority groups must mature in the point where self-consciousness is not a motivating factor for complaints.”

On Dec. 29, 1966, Joseph Waller – now known as Omali Yeshitela — stripped the mural from the wall as he was leaving the building. He was arrested and charged with felony theft and spent at least 22 months in prison.

Thirty years later, during extensive renovations to city hall, city council members agreed to spend $50,000 to commission two landscape murals by Tarpon Springs artist Christopher Stills to be hung in the staircase. On July 18, 1998, the Times published the article “Need Mural to Grace City Hall’s Blank Wall Again.”

In a letter dated Aug. 10, 1998, the newly formed Concerned Citizens Action Committee sent a letter to Mayor David Fischer regarding the proposed murals and requested to appear before city council on Sept. 10.

On Sept. 10, council resolved to refer the issue to the Public Arts Commission. Councilmembers Kathleen Ford and Ernest Fillyau proposed a resolution that the city council be requested to organize a ceremony to dedicate the new art to be installed in city hall and to issue a public apology to the community. The resolution also requested that the city’s legal department investigate the process to restore Omali Yeshitela’s civil rights.

Nearly 34 years after his arrest, Yeshitela’s rights were restored by Gov. Bush and the Cabinet in 2000.

On Sept. 11, 1998, the commission was unanimous in its recommendation to council to place the Stills murals in council chambers, keep the Hill mural on the north side of the staircase in place, and the wall on the south side of the staircase should be devoid of any artwork. On Nov. 12, 1998, council passed Resolution NO. 98-651 regarding the placement of the Stills murals.

Years passed, and on Aug. 18, 2015, the City Hall Stairwell Mural Project Committee was formed to revisit the issue of the blank wall in city hall and to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the removal of the mural. The Project Committee issued a Request for Proposal seeking “Art that will respect the history of the events surrounding the tearing down of the original mural and that will celebrate a city of opportunity for all.”

The project budget was $50,000, and the deadline for applications was set as Oct. 3, 2016. The work of the Project Committee ended in June 2017, and the city council once again voted to leave the wall blank.

The wall remains blank, and more importantly, absent of a plaque commemorating the event that ignited the civil rights movement in St. Petersburg.

Our stories are beautiful, complicated, and messy, but our stories matter and they must be told. Around the country and throughout the world, stories are being remembered, and histories are being preserved.

From the Legacy Museum and National Peace and Justice Memorial in Montgomery, Ala., to the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C., to the identification of homes from which Jewish families were sent to death camps in Germany to our own African American Heritage Trail in St. Pete — history is being honored and preserved.