By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

When the Civil War ended in 1865, the Union Army was compelled to occupy the South to prevent the slaughter of newly freed black people by angry and impoverished former Confederates. The death, destruction, violence and terror against the newly freed were unparalleled in United States history.

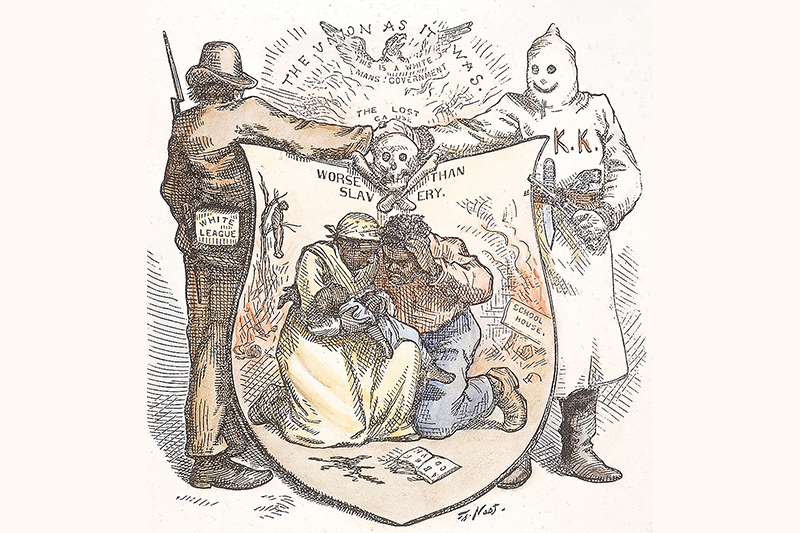

President Ulysses S. Grant spent his two terms as the Reconstruction president. He defeated the Ku Klux Klan with a great deal of success. However, ensuring voting rights for black Americans in the southern states was an extremely difficult fight that continued throughout Reconstruction and afterward.

For the first time, after 1868, Constitutional Amendments were passed giving the rights to vote, to due process, and to equal protection under the laws for black people (men). During Reconstruction, the 13th (1865), 14th (1868), and 15th Amendments (1868) to the United States Constitution were adopted, pressed by a united and Union [Republican] Congress and president.

These Amendments are often called the Civil War Amendments or Reconstruction Amendments. For the first time in American history, people who had participated in the Confederate insurrection, mostly white, were denied the right to vote.

The 14th Amendment, Section 2, denied the right to vote to any male who participated “in rebellion…” The 14th Amendment, Section 3, forbade the election of any “…Senator or Representative in Congress…or [to] hold any [elected] office…[if they] shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion…or given aid or comfort to the enemies [of the Union].”

This complete reversal of the status quo was met by unadulterated hatred, resistance and violence by the defeated Confederates. As a result, President Grant had to send thousands of Union troops to the South to protect the enfranchisement of black people and keep the polling places open.

Black people met anger, violence and hatred at every attempt to vote, but vote they did! Reconstruction lasted until 1880 with mostly African Americans in charge. Additionally, many Northerners came south to help open schools and educate black people. The Freedmen’s Bureau, banking institutions, and voting places were protected by Union Troops, which enflamed and enraged the South.

There had been one prevailing negative view by American historians of the effects of Reconstruction until W.E.B. DuBois’ seminal work “Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880.” The older view held that nothing was accomplished by the newly freed except confusion and corruption led by ignorant black politicians. DuBois’ research, first revealed in his doctoral dissertation at Harvard University, proved this view to be incorrect. In fact, black Americans miraculously achieved a great deal during Reconstruction.

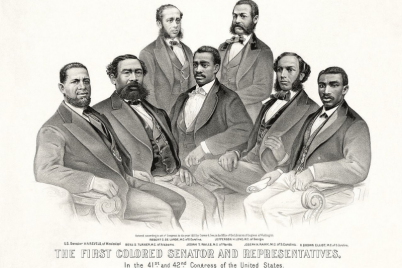

Undoubtedly, the presence of Union troops helped keep the peace. For the first time, black Americans could and did vote, held state constitutional conventions, wrote fair and just laws, elected a governor, United States Senators and Representatives, and other elected officials.

Black businesses sprung up; farmers began planting for themselves and black communities began to flourish. Black voters were uniformly Union supporters or Republicans, while former Confederates and their supporters were encapsulated in the Democratic Party. Southern resistance to Reconstruction was fierce; northerners began to tire.

Support for Reconstruction began to wane before the end of President Grant’s second term. By 1876, his last year in office, uniform support for the newly freed had greatly weakened.

In the presidential election of 1876, a compromise was entered into by Republicans and Democrats that resulted in the election of Republican Rutherford B. Hayes in a hotly contested presidential election.

Historian Eric Foner sums up the commonly held notion in “Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution” that by 1877, the growing conservatism of the Republican Party and the humanitarian impulse that had helped create the party and the commitment to equal citizenship that evolved during the war and Reconstruction had lessened.

“Southern issues, however, played a steadily diminishing part in Northern Republican politics, and support for the idea of federal intervention to enforce the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments continued to wane,” Foner posited.

Many Southerners opposed both Grant, the outgoing Republican president, and Rutherford B. Hayes, the 1876 Republican presidential candidate. In contests in four Southern states, Hayes won the presidency by one electoral vote.

In return for Southern support of Hayes, Republicans agreed to support the withdrawal of federal troops from the former Confederate States, formally ending Reconstruction. Called the Compromise of 1877, South Carolina, Florida and Louisiana agreed to certify Hayes as the president in exchange for the removal of federal troops from the South.

Hayes complied with the compromise. He quickly ended Reconstruction and withdrew federal troops from the last two occupied states, South Carolina and Louisiana. The right to vote was the first victim of the ensuing assault on Constitutional rights for African Americans and is still a struggle.

The compromise resulted in an appropriations bill for the army that included the prohibition of any military occupation of any state by the United States Army. By the 1878 election, Congress was dominated by the Democratic Party, and it passed the Posse Comitatus Act in 1878 to prohibit any future president or Congress from directing, by military order or federal legislation, the imposition of federal troops in any U.S. state.

Author Ron Chernow wrote in his book “Grant” that at the collapse of Reconstruction, southern blacks were left at the mercy of “Jim Crow segregation, lynchings, poll taxes, literacy tests, and other tactics designed to segregate them from whites and deny them the vote” for 80 years.

It is an enduring legacy and one that African Americans need to be aware of.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.