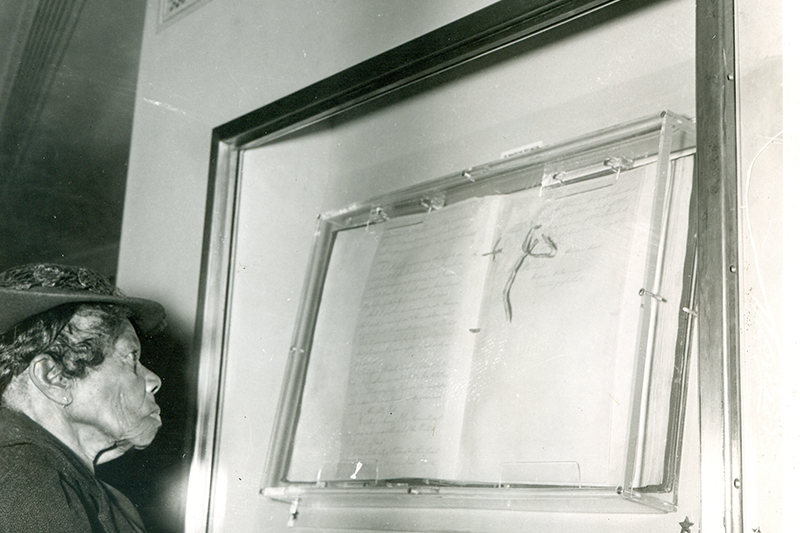

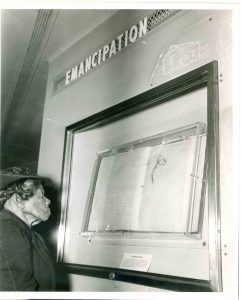

Formerly enslaved, Sally Fickland, views the Emancipation Proclamation in 1947.

By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

To place the final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation into context, it is essential to understand that the freedom of American slaves was directly tied to the secession of the Southern states just prior to the beginning of the Civil War.

On Dec. 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the United States, followed by 10 additional Southern states withdrawal from the Union within the following months, calling themselves the Confederate States of America.

On April 12, 1861, the Confederates attacked the Union’s Fort Sumter outside of Charleston, S. C., and began the Civil War. Even before that, according to “The New York Times Disunion: 106 Articles from the New York Times Opinionator,” President Abraham Lincoln’s election guaranteed that at least a few slaveholding states would secede.

“Though Lincoln the candidate took pains to emphasize that he would not move against slavery where it already existed, and as president-elect remained studiously silent on the question, many Southerners believed that the man from Illinois and his newly empowered Republican Party would move aggressively to limit slavery’s expansion, isolating the South and putting the institution on a short road to extinction.”

Formerly enslaved, Sally Fickland, views the Emancipation Proclamation in 1947.

In Dec. of 1860, Frederick Douglass expressed optimism after the secession of South Carolina from the Union. He heaped scorn upon South Carolina by stating it preferred “…to be a large part of nothing, to being any longer a small part of something.”

Douglass hoped it would lead the way to slavery’s abolition. Federal anti-slavery policies, however, began in earnest only after the concept of slaves as “contraband of war” took hold under the Union Army.

In May 1861, General Benjamin Butler refused to return hundreds of runaway slaves from Fort Monroe in Virginia. After that, President Lincoln and Congress recognized the usefulness of freed blacks to the Union Army.

In Aug. of 1861, Congress passed and President Lincoln signed “The First Confiscation Act” that required the seizure of all Confederate property, including slaves “employed in or upon any fort…or in any military … service.”

On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln signed the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. The final draft of the Emancipation Proclamation was signed on Jan. 1, 1863, and stated, among other things, “…I do order and declare that all persons held as slaves within said designated States, and parts of States, are, and henceforward shall be free; and that the Executive government of the United States, including the military and naval authorities thereof, will recognize and maintain the freedom of said persons.”

Lincoln authorized the recruitment of blacks into the armed forces, and by the close of the Civil War, more than 400,000 black people fought with the Union Army.

These heroes deserve to be celebrated and talked about. Children need to learn about their bravery. Many escaped for the sole purpose of joining the Union Army to fight for freedom. These men and women were our first Drum Majors for Justice. Let us honor them by honoring The Emancipation Proclamation every New Year’s Day.

This proclamation is one of the most critical documents in African-American history and deserves to be celebrated by all Americans as one of the first steps toward black America’s full liberation and right to full integration into the protections that come with freedom.

It carefully–when read in its entirety with the preliminary Emancipation Proclamation signed by President Lincoln 100 days earlier–lays the foundation for full citizenship for all black people. It established, without question, the fundamental purpose of the Civil War was the abolition of slavery.

It took several years after the defeat of the Confederacy in 1865 for the federal government, under President Ulysses S. Grant, to implement necessary protective measures to ensure these freedoms.

President Grant instituted new, brave and innovative actions such as creating the first attorney general’s office to prosecute the Ku Klux Klan, signing the first Civil Rights Act, passing the Civil War Amendments to the U.S. Constitution and starting the Freedmen’s Bureau.

Most historians agree President Grant’s actions led to the success, however short, of the Reconstruction Era.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.