By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

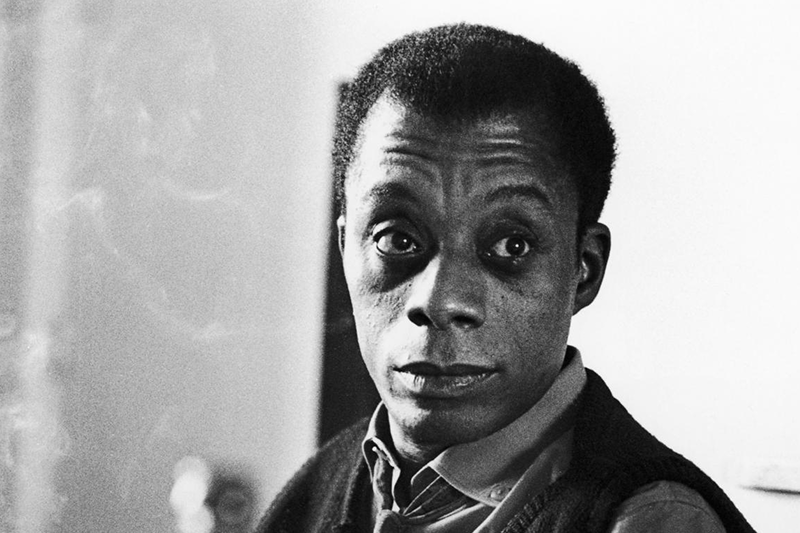

Without a doubt, James Baldwin was one of the most gifted American writers ever published. He came of age in the midst of 20th-century racial turmoil that defined and engulfed generations of African Americans. He was the intellectual voice of his generation and ones to follow.

Born in Harlem, a black neighborhood in New York City on Aug. 6, 1924, Baldwin’s biological father is unknown; his stepfather was a store-front preacher, who has been accused of being abusive to him as a child. Baldwin graduated from De Witt Clinton High School in 1942. As he grew into manhood, he was fortunate enough to study under Harlem Renaissance poet Countee Cullen.

Being black in America haunted Baldwin, and in 1948, after being awarded a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship, he followed other black artists such as Josephine Baker and Richard Wright and moved to France. France became his home, where he remained until the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement.

His language was his own with his own references and his own intellectual vigor. Baldwin was often criticized for not writing in a more simplistic style. He was often compared to the French existentialists rather than other African-American writers.

While in France, Baldwin published “Go Tell It on the Mountain,” “Notes of a Native Son” and “Giovanni’s Room.” His works required concentration and a fundamental understanding of politics, history and culture. He was never an easy read. His work was, however, always a thing of beauty.

For more than 20 years, he wrote with passion about the effects of racism in America. In 1963, in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, Baldwin published, “The Fire Next Time.” It was a warning of the violence to come.

He became a spokesperson for the Civil Rights Movement upon his return to America and became a part of the Freedom Movement.

In 1968, after his return, he published “Tell Me How Long The Train’s Been Gone.” This book allowed him to reflect upon who he had become by positing himself in the character Leo Proudhammer where he states: “The day came when I wished to break my silence and found that I could not speak: the actor could no longer be distinguished from his role.”

Baldwin became a beloved political activist and continued to both write and speak. He traveled to the southern United States and became known as a peerless public intellectual of profound genius and compassion. Later in his life, Baldwin wrote an introductory essay titled “The Price of the Ticket” to a collection of his essays spanning from 1948 to 1985 of the same title:

“Each of us, helplessly and forever, contains the other–male in female, female in male, white in black, and black in white. We are a part of each other. Many of my countrymen appear to find this fact exceedingly inconvenient and even unfair, and so, very often, do I. But none of us can do anything about it.”

James Baldwin died of cancer on December 1, 1987, in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, at his home in France.

In 2017, the filmmaker Raoul Peck completed the documentary about James Baldwin entitled “I Am Not Your Negro.” The film received many accolades. The Guardian proclaimed it to be “…a striking work of storytelling…One of the best movies about the Civil Rights era ever made…This might be the only movie about race relations that adequately explains–with sympathy–the root causes.”

The New York Times called it: “Thrilling…a portrait of one man’s confrontation with a country that, murder by murder, as he once put it, ‘devastated my universe’…One of the best movies you are likely to see this year.”

Indeed, Baldwin’s legacy will undoubtedly be his ability to put into words the tremendous complexity of race in America. In the concluding paragraph of his introduction to “The Price of the Ticket” he wrote:

“The price the white American paid for his ticket was to become white — : and, in the main, nothing more than that, or, as he was to insist, nothing less. This incredibly limited not to say dim-witted ambition has choked many a human being to death here: and this, I contend, is because the white American has never accepted the real reasons for his journey. I know very well that my ancestors had no desire to come to this place: but neither did the ancestors of the people who became white and who require of my captivity a song. They require of me a song less to celebrate my captivity than to justify their own.”

Earlier this month, an adaptation of Baldwin’s “If Beale Street Could Talk” hit the theaters. He still lives among us.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.