Ninety-one-year-old Martha Bellamy recalls living and learning from her grandfather, who was born into slavery.

BY GABBY SETTLES, Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — As we continue to commemorate our elders and reflect on the lives and legacies of Black Americans before us, there’s a powerful voice to add to the celebrations — the voice of Mrs. Martha Bellamy.

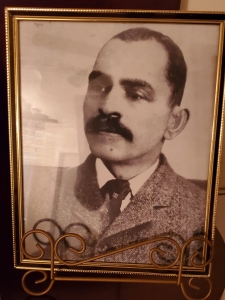

Mrs. Bellamy, a 91-years-young St. Pete resident, shares the story of her grandfather Henry Clay Richardson, who was born into slavery and lived through it as a young child. Once free, Richardson grew up to become a businessman, benefactor and leader of his community.

“He was just wonderful,” Mrs. Bellamy remembers of her grandfather.

On March 17, 1857, Henry Clay Richardson was born on a plantation in Villanow, Ga., a village located not far from the borders of Tennessee and Alabama. Mrs. Bellamy said he told her about some of his experiences as a child, growing up in the middle of the Civil War.

“He said they [the children] would be out in the yard playing, and they would hear the guns shooting with the troops marching up what they used to call the valley,” she recalled. “The wives and the children would be hollering and crying.”

Richardson was six years old when the Emancipation Proclamation was signed, but it wasn’t until two years later that the state of Georgia freed its enslaved population. Richardson’s mother took him and his brother Richard and left the plantation, walking for 20 miles until coming to a town called LaFayette, Ga., a place that Richardson would call home for the rest of his life.

Mrs. Bellamy said he never spoke about it directly, but she believes that Richardson, who was of mixed heritage, was fathered by the man who owned him and his family. She said the family moved to Oklahoma after slavery ended, but they returned to Georgia years later to convince Richardson to come back with them. Richardson, now an adult with a family of his own, refused.

He was a man of many trades — in addition to raising chickens and growing vegetables, he had a successful business as a carpenter and brick mason. His granddaughter said he was well known around town and was often called to repair mansions or build homes from the ground up.

Richardson owned multiple acres of land, where he built 10 houses for his neighbors “so people would have decent places to live,” said Mrs. Bellamy.

Richardson wasn’t just a businessman, he also used his talents to give freely to others in the community, such as building a small apartment building for wanderers and travelers to stay during the night. Richardson’s daughter, Lizzie Richardson Davis — Mrs. Bellamy’s mother — would cook dinner for the travelers, and in the morning, she would pack them lunch for their continued journey.

Richardson also donated a portion of his land for a church and then built the church free of charge. Mrs. Bellamy, a young girl at the time, said that’s just the kind of person he was.

“Those are the kind of things I grew up with,” she recalled.

When he was older, Richardson lived with Mrs. Bellamy, her mother Lizzie and her father John D. Davis, who also had an industrious spirit. He produced dairy and slaughtered cows and hogs to supply the local stores with meat, butter and milk.

Mrs. Bellamy had two siblings, but both passed away — her sister as a baby, and her brother died at age 16 of a ruptured appendix. As the only child in the home, she said she loved to spend time with her grandfather. He would often walk her to school, and she would, in turn, carry his lunch to him on his construction sites.

Richardson also put his construction skills to use for his beloved granddaughter.

“He built me a playhouse that was big enough for a person to really live in,” Mrs. Bellamy stated. “After I got where I didn’t want a playhouse anymore, a man rented it and lived in there.”

After family dinners each night, Mrs. Bellamy would spend more quality time with her grandfather.

“I had a little chair where I would sit right down beside him. He would go over ABCs, reading the Bible to me and it was just a great thing growing up with him,” Mrs. Bellamy reminisced.

She said everyone in town loved and respected her grandfather and their family. Henry Clay Richardson died in LaFayette, Ga., in 1951 at the age of 94.

Even though her grandfather had passed away, his hard-working spirit remained with Mrs. Bellamy. She remained in LaFayette, Ga., for two years before joining the military at age 22.

“I’m the first Black woman to join the army from my little hometown,” Mrs. Bellamy stated.

Jim Crow was rampant throughout the South, and segregation was felt heavily throughout the military. The army was slow to desegregate their officers; President Harry Truman issued an executive order to desegregate the military in 1948, but the military took their time in doing so, according to the U.S. Army Center of Military History. Integration didn’t fully occur until 1954.

Mrs. Bellamy describes that when she first entered the army, the sleeping quarters in the barracks were divided into segregated cubicles.

“It was cut down in little sections. You had your private stuff, and there would be two people in each cubicle, but they would have to be two Black people, two white people,” she recalled. “You just had to learn how to deal with it.”

Bootcamp training for Mrs. Bellamy took place in Virginia, where she said the women used a portion of the men’s facility. In addition to integrating in 1954, the army also opened the Women’s Army Corps Center at Ft. McClellan in Alabama, and Mrs. Bellamy went to the base to assist in the opening.

She received special training in the army’s baking school and transitioned to several army bases throughout the South, where she ran the mess halls at each. She continued her military career for “six years, six months and 16 days” until she married her husband, Master Sergeant Abram Bellamy, in 1955. They adopted a son, Eric D. Bellamy (better known as Dwayne), and were married for 30 years before divorcing.

Once Mrs. Bellamy left the army, she enrolled at a vocational school, where she learned dressmaking and tailoring. She turned it into a business, in addition to cooking food for parties at night. She enjoyed her work.

“It was just great for me,” she reminisced. “Eventually, arthritis caught up with me. So I’m a 100 percent disabled veteran now.”

Mrs. Bellamy moved to St. Pete in Dec. of 1996 for the warmer climate, and it was here that she found a new venture: buying and selling condominiums.

“I would see people buying and selling, so I got into that. It has helped me along the way,” Mrs. Bellamy said. “Since I’ve been down here in Florida, I’ve bought and sold eight condos. I’m in my last one where I’m gonna stay because I’m 91 years old, and in five months, I’ll be 92 years old, so I can’t be moving around now.”

While Mrs. Bellamy may have settled down, her diligent spirit hasn’t. She still takes care of her bills and writes her checks. She was cleaning her condo on her own, she said with a chuckle, but the Veteran’s Association now sends someone three times a week to help her.

Mrs. Bellamy wants the younger folks in the Black community to know they can have financial security too, but it comes with discipline and leaves little room for excuses.

“Set your mind on owning something of your own,” she asserted. “Settle yourself and reach towards saving what you can. You can’t save a lot now because things are bad, but try to save some of your money. Don’t work from one payday to the next and be broke.”

She also said Black Americans need to start spending more money within their own community to generate wealth.

“We’re going to have to set our mind on [making] things better for ourselves,” Mrs. Bellamy said. “Use our money for ourselves. Educate our children, teaching them from the beginning how to come on up and make it on your own.”

When it comes to racial equality in the nation, she wants people to finally understand that “Black people are human just like they are.”

“Black people worked to help build the country up to where it is now. Stop trying to look over the Black people because we’re smart,” she stated.

If her grandfather were alive today, Mrs. Bellamy said he’d have some firm words for us, too.

“He would just be upset over the way things are. He would say everybody needs to settle down and remember that the Lord has all the power … and stop all this foolishness and lets everybody start respecting each other.”

Just as her grandfather was beloved by the citizens in LaFayette, Ga., the St. Petersburg community has made sure they show the same respect for Mrs. Bellamy. Last year, her friends surprised her with a COVID-19 safe drive-by celebration for her 91st birthday.

Now that she has received her COVID-19 vaccine, Mrs. Bellamy is looking forward to celebrating her 92nd birthday, visiting with her son Dwayne and traveling across the country.