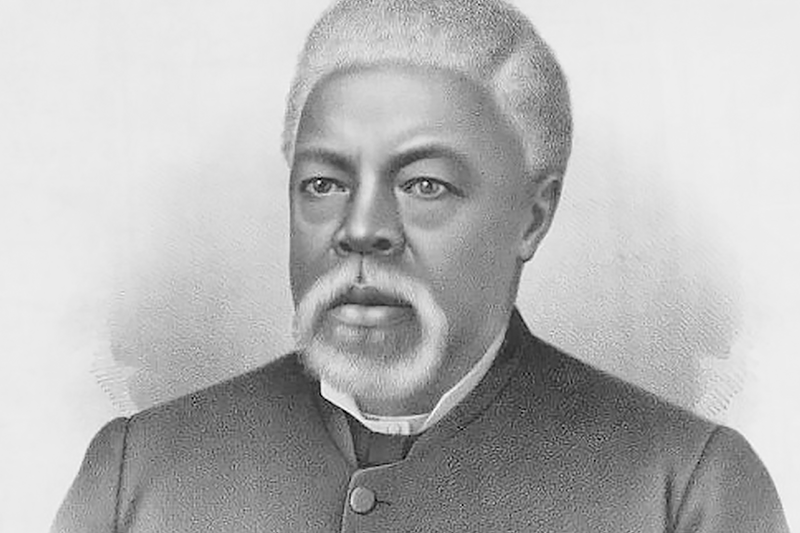

Baptist minister Ulysses L. Houston, one of the pastors who met with Sherman, led 1,000 blacks to Skidaway Island, Ga., where they established a self-governing community with Houston as the “black governor.”

By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

In W.E.B. DuBois’ seminal work “Black Reconstruction in America, 1860-1880,” he spoke approvingly of the actions taken by the abolitionists at the end of the Civil War. He felt they understood the true path to freedom lay in economic empowerment for the newly emancipated.

DuBois agreed with the abolitionists’ recognition that Negro progress and assimilation into American society depended upon a sound economic footing after the defeat of forced, free labor.

He stated, “They saw that the Negro needed land and education and that his vote would only be valuable to him as it opened the doors to a firm economic foundation and real intelligence…to give him land and schools, the battle would be won…however…Stevens could not get…his plan of land distribution, and Sumner failed…in his effort to provide for a national system of Negro schools.”

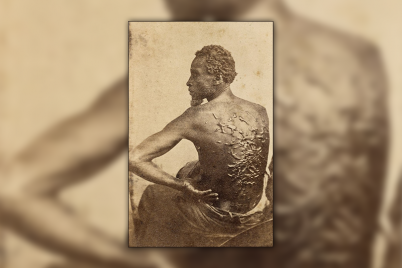

It is clear they understood the notion of reparations for nearly 240 years of slavery.

According to Harvard historian Henry Louis Gates, “the federal government’s massive confiscation of private property — some 400,000 acres — formerly owned by Confederate landowners, and its methodical redistribution to former black slaves” occurred because black people demanded it after the Civil War.

This concept was codified in Union General William T. Sherman’s “Special Field Order No. 15” on Jan. 16, 1865, which consisted of three parts.

Section One

“The islands from Charleston, south, the abandoned rice fields along the rivers for thirty miles back from the sea, and the country bordering the St. Johns river, Florida, are reserved and set apart for the settlement of the negroes now made free by the acts of war and the proclamation of the President of the United States.”

Section Two

“At Beaufort, Hilton Head, Savannah, Fernandina, St. Augustine and Jacksonville, the blacks may remain in their chosen or accustomed vocations–but on the islands, and in the settlements hereafter to be established, no white person whatever, unless military officers and soldiers detailed for duty, will be permitted to reside; and the sole and exclusive management of affairs will be left to the freed people themselves, subject only to the United States military authority and the acts of Congress. By the laws of war, and orders of the President of the United States, the negro is free and must be dealt with as such…”

Section Three

“…each family shall have a plot of not more than (40) forty acres of tillable ground, and when it borders on some water channel, with not more than 800 feet water front, in the possession of which land the military authorities will afford them protection, until such time as they can protect themselves, or until Congress shall regulate their title…”

Field Order 15, signed in 1865, covered 400,000 acres of land that would be redistributed to newly freed black people. A later order provided for the use of a mule for each 40 acres.

The importance of General Sherman’s Field Order 15 is the fact that it acknowledged that newly freed black people deserved to be compensated for more than 200 years of brutally enforced slavery.

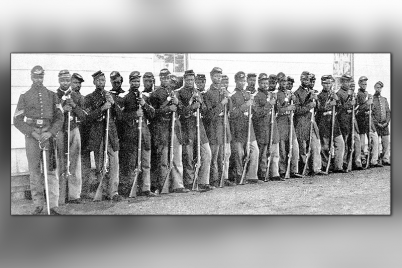

General Sherman and President Lincoln also agreed that black people deserved acknowledgment of the contributions they had made to the Union’s victory.

The amazing aspect of this notion codified in Field Order 15, was that it came from 20 black ministers who met with General Sherman and Secretary of War Edwin McMasters Stanton on Jan. 12, 1865, in Savannah, Ga. They also asked for the land and the mule to till the ground.

This hopeful resolution was cut off for all who failed to take immediate advantage of the order because President Lincoln was shortly thereafter assassinated, and unfortunately, Lincoln’s predecessor was a Confederate sympathizer.

He overturned Field Order15 in the fall of 1865 and mightily worked to return the land to the Confederates who owned it prior to their defeat in the Civil War.

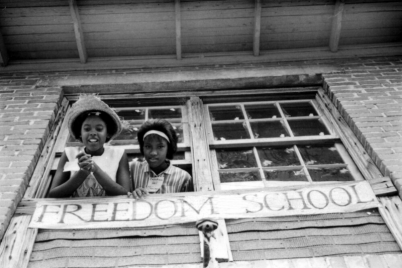

This historical reversal is a common thread throughout American history, which is why constant vigilance is always required and why black people should not sleep on their aspirations for full civil rights. We must forever continue to assert and struggle for them.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.