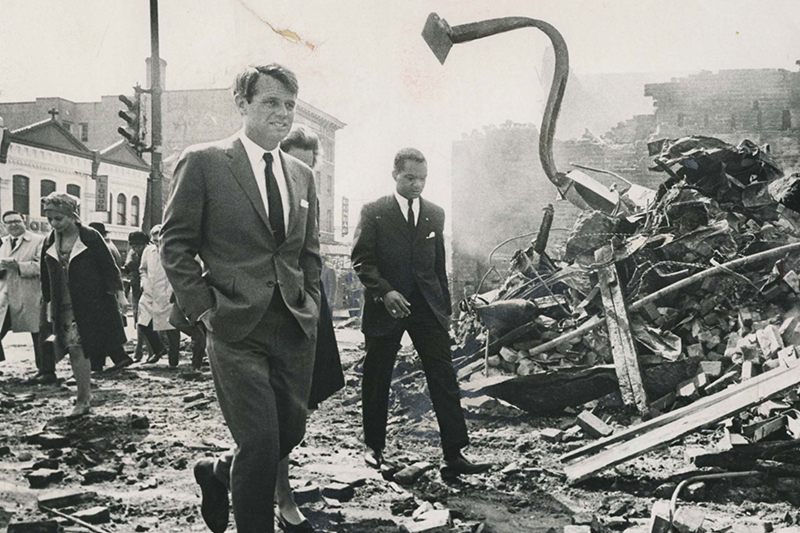

Robert Kennedy and Rev. Walter E. Fauntroy toured the damages after days of rioting in Washington, D.C., when Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. Two months later, Kennedy would be killed in Calif.

BY JENNIFER GAMBLE-THEARD, M.ED., ASALH Historian

The Civil Rights Movement of the mid-20th century was a turning point that initiated many crucial events in the United States. It was a vast movement of thoughts and actions that received pushed back against the stuck-in-place social and political inertia of the vast majority of non-black American citizens.

For too long, African Americans had been boxed into an existence created by rules and attitudes based on greed, arrogance, ignorance and hate. Fed up with injustices and frustrated from pent-up emotions, the descendants of the black diaspora (slaves) became the resistance against institutionalized racial segregation, discrimination and inequality.

Between 1955 and 1968, acts of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience produced crises and productive dialogues between activists and government authorities.

Leaders of the Civil Rights Movement chose the tactic of nonviolence as a means to dismantle the intricacies and mechanisms of injustices that had been systematically inflicted upon African Americans for centuries. In the 1960s, elements of black activism began to use the term of nonviolence in a broad interpretation.

During this time, the Civil Rights Movement moved forward in undercurrents of turmoil as civil progress seemed to be an elusive dream. African Americans continued to fight for equal rights in American society with nonviolent tactics such as marches, sit-ins, organized protests, peaceful rallies and political appeals, but many young people and extreme left thinkers grew tired of Martin Luther King, Jr.’s nonviolent strategies.

There were those who had decided to use force when necessary and were more interested in a militant brand of activism. The movement was beginning to take on a new face.

After decades of racial, economic and politically forced poverty in inner cities across the U.S., sources of tensions developed. Several cities across the country had devastating race riots as early as 1917 in East St. Louis, Rosewood, Fla., in 1923, Watsonville, Calif., in 1930, Harlem in New York City in 1943, just to name a few.

There happened to have been race riots in any given city somewhere in the United States each decade from the 1820s. By the time of the Civil Rights era of the 1960s, race riots began to occur with more frequency and intensity.

Many cities from coast to coast, north to south and scattered about the mid-west that had sizable African-American populations had the potential to explode at any time. In 1967 and 1968, city after city began to erupt with blacks expressing their anger and suppressed frustrations.

After a year of multiple explosive situations that engulfed the country in 1967, the climax of the movement began to take form. The year 1968 became the pivotal year of radical change.

That year in history impacted black people more than any other time within the past one-hundred year time period. Events of ‘68 still reverberate to this day, altering the inertia of the United States.

Barely into the new year in early February, the Orangeburg Massacre in South Carolina resulted as black students attempted to desegregate a bowling alley on the campus of South Carolina State University. From that attempt, three students were killed and 28 others were shot in their backs. Nine officers stood trial for excessive force but were acquitted of all charges.

In March, more than 1,000 Howard University students held a five-day sit-in on campus protesting its ROTC program and the Vietnam War. They demanded a black studies program, black history infused into the curriculum and school involvement in the community. The protest ended with some of their demands met.

On March 31, President Lyndon Johnson announced his decision not to seek re-election, leaving black people fearing the loss of federal support for civil rights, and realizing they had to fine tune their efforts.

On April 4, Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn, while there showing support for the sanitation workers’ strike. He was also in the process of organizing a national Poor People’s march on Washington. Civil Rights leaders pleaded for peace, yet riots broke out in more than 125 U.S. cities before Dr. King was buried on April 9 in Atlanta.

Immediately following the death of Dr. King, the country erupted in violent riots, the most severe occurring in Washington, D.C., Chicago and Baltimore. Even Tampa and Miami had a few volatile moments. More than 40 people were killed during the month of protest, which led to greater racial tensions between white and black Americans.

By the end of April, the Civil Rights Act of 1968 was passed, which prohibited housing discrimination based on race. This law opened up the opportunity for African Americans to expand the boundaries of where they could buy homes and live.

On June 5, Robert Kennedy, brother of assassinated President John Kennedy, was slain after winning the California presidential primary.

In Sept., the first Black Studies program was founded at San Francisco State University. Students of color collaborated to get a Chicano Studies program, plus other programs, which would draw attention to the relevance and attributes of other cultural groups.

In Oct., United States athletes at the Olympics took a stand in Mexico City. Tommie Smith and John Carlos silently raised black-gloved fists during the National Anthem. Some U. S. reactions considered their act as “an embarrassment visited upon the country.” Despite the negative storm, they were considered heroes by the black community.

On Nov. 5, Republican Richard Nixon won the presidency. Nixon had campaigned to fight for law and order and stand for the “silent majority” (same stand as Trump). The good news at the same time was that Shirley Chisholm became the first black woman to be elected to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Although the Civil Rights Movement was a decades-long struggle, the precision in timing achieved constitutional and legal rights that African Americans had fought for more than 300 years. With roots dating back to the Reconstruction era during the 19th century, the movement achieved its most substantial legislative gains in the mid-1960s after years of direct actions and protests from African Americans and their supporters.

Those most important actions occurred from the 1950s until 1968. Since then, there have been political and social gains of many kinds. African Americans helped to elect government representatives of our choice and most importantly to select the first black president in 2008. We have maintained a political awareness that should keep us active and involved in what happens to the future of America.

Those most important actions occurred from the 1950s until 1968. Since then, there have been political and social gains of many kinds. African Americans helped to elect government representatives of our choice and most importantly to select the first black president in 2008. We have maintained a political awareness that should keep us active and involved in what happens to the future of America.

Black pride has been a key to our social evolution in American; yet, we must continue to be aware of steps that must still be climbed in economics, education, and even global diversity. We must remain committed to the cause.

We must teach our children how far we have come from the turmoil of the Civil Rights Movement, and more importantly, the necessity to continue the fight for equality, justice and progress.

Jennifer Gamble-Theard, M.Ed. is a retired Pinellas County educator in the study of history and language. She is also the historian for the St. Petersburg Branch of ASALH.