BY J.A. JONES, Staff Writer

CLEARWATER — When a Clearwater resident went looking for a family member’s gravestone at an area cemetery and couldn’t locate it, a decades-old theory proved true.

The St. Matthew Missionary Baptist Church cemetery was relocated in the 1950s. However, many Clearwater residents suspected dozens of unmarked graves were left behind rather than reinterred at the Parklawn Memorial Cemetery for African Americans in Dunedin, as recorded. Today, at least part of the land that once held the cemetery has become the location for human resources company FrankCrum’s national headquarters, 100 S. Missouri Ave.

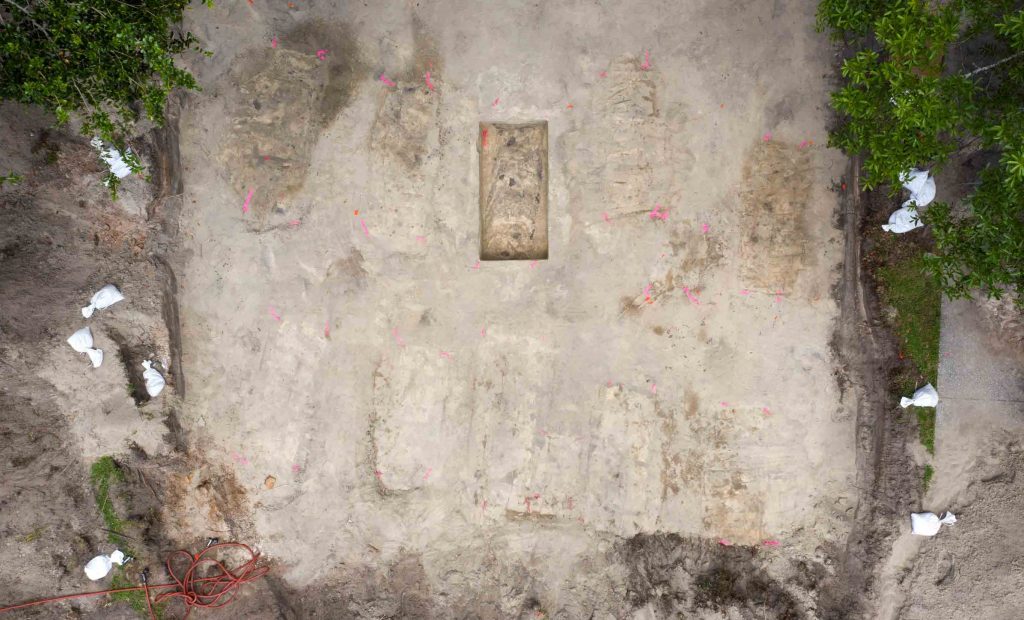

The presentation also included aerial images of the scanned grounds and images from the ground-penetrating devices showing outlines of coffin-shaped structures in Tampa.

And, as it turned out, that wasn’t the only cache of graves buried beneath newer structures. Another series of graves were located at the former North Greenwood Cemetery site – now beneath what became the old Curtis Fundamental School at Holt and Engman Streets.

In August, the NAACP Clearwater/Upper Pinellas County Branch held a public information meeting to share findings from the geological surveys and the ongoing investigation. NAACP President Zebbie Atkinson, IV, hosted a panel of archeologists who surveyed the sites, including the University of South Florida’s Paul L Jones, Jeffrey T. Moates, and Becky O’Sullivan, and archaeologist Erin McKendry with the Cardno firm.

The Clearwater Heights Reunion Committee, formed in 2016 by Barbara Sorey-Love, began to press for answers after the Tampa Bay Times investigated and revealed hundreds of graves from Zion Cemetery were still located under the area of Robles Park Village in Tampa.

Their investigation began to heat up in 2019 when the CHRC reached out to other community organizations, including the Clearwater Historical Society (CHRC) and the NAACP Clearwater/Upper Pinellas County Branch. The Clearwater Heights Reunion Committee and CHRC reached out to Frank Crum, Jr., the company’s CEO, and initially got no response.

“But,” said Atkinson, “Once the NAACP became involved, it took a very simple phone call to Mr. Crum.”

Atkinson said they set up a meeting with Crum and his children, who are now also part of the business. He told the Crums were amenable to CHRC’s request to have the property scanned.

While an initial geological scan conducted by USF failed to turn up anything, one of the great-grandchildren of the person who owned the property when the cemetery was functioning heard about the quest.

“They reached out to say, ‘you need to look more north and east’ — and that’s where the cemetery was,” acknowledged Atkinson.

The presentation by O’Sullivan tracked the historical “erasure” of the cemetery. “The cemetery was started in 1909; by 1926, we definitely have active burials that are going on, on this property,” said O’Sullivan, an archaeologist with the Florida Public Archaeology Network through the University of South Florida.

But city records through the decades also noted multiple sales of surrounding land parcels for commercial purposes. O’Sullivan noted racist practices of the Clearwater City Council, including, as recorded in a St. Petersburg Times article dated 1954, plans by the city council “to confine Negro homebuilding and purchasing to the existing area.” Fines and liens were placed on Blacks who couldn’t pay for city improvements to the roads and sewers.

“The church Board of Trustees for the St. Matthews Baptist Church in May of 1955 sold the cemetery property to three white developers for $15,000,” noted O’Sullivan. “The money was used for much-needed improvements to the church and likely to pay off the lien that had been put on the property for road improvements.”

The three men — Chester McMullen, Milton Jones, and T.R. Hudd – were supposed to move the graves to a new cemetery they established in Dunedin, Parklawn Memorial Cemetery for African Americans, shared O’ Sullivan. “It’s unclear how many burials were moved from St. Matthews to Parklawn after they purchased the property.”

Further research indicated that some graves might have been relocated to North Greenwood Cemetery, another African-American cemetery that was supposedly emptied by the three developers and relocated to Parklawn. By 1959, the St. Matthew cemetery property had been sold a handful of times more, sometimes in pieces. By 1961, construction of the Montgomery Ward store had begun on the property.

Archaeologist Erin McKendry said the North Greenwood Cemetery was “emptied” in 1954 – with graves also designated to be sent to Parklawn. In 1961, Palmetto Elementary School was built on top of the one area of the cemetery.

The presentation also included aerial images of the scanned grounds and images from the ground-penetrating devices that showed the outlines of coffin-shaped structures dotted around the properties.

“It brought back so many memories of the community…and closure is needed,” said Sorey-Love. “I think we’ve waited long enough, and it’s time to continue to move forward. We look forward to moving forward for a resolution.”