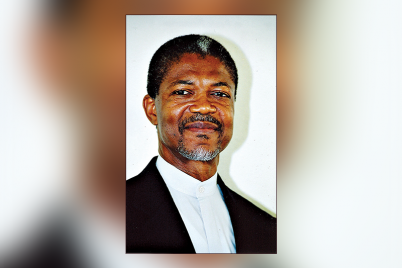

Dr. Kemesha Gabbidon helps prevent the spread of infectious disease as a community health advocate and postdoctoral research fellow at USF’s St. Petersburg campus.

ST. PETERSBURG — As a young girl playing doctor in her hometown of Kingston, Jamaica, Kemesha Gabbidon’s patients only ever seemed to come down with two specific ailments: asthma, which Gabbidon herself suffered from as a child, and bronchitis.

“I used to call it brown-chitis,” Gabbidon said laughingly. “My mom bought me this fake stethoscope, and I carried around a little notepad, diagnosing my friends with asthma and brown-chitis.”

Today, Gabiddon is a real doctor of a different sort. Rather than diagnose patients, she helps prevent the spread of infectious disease as a community health advocate and postdoctoral research fellow at USF’s St. Petersburg campus. Gabbidon’s research focuses on topics like reproductive health and health equity. Through a recent initiative, she works closely with local individuals and communities most affected by HIV in order to reduce the spread of the disease.

“My goal in public health is to help with prevention efforts,” Gabbidon said. She has a special interest in reaching at-risk youth, instilling in them the knowledge they need to lead safer and healthier lives.

It might sound morbid to many people, but Gabbidon has always been fascinated by infectious diseases. As a student, she devoured grim literature about pandemics like it was light reading. Her interest was so acute that for many years Gabbidon would eagerly discuss the stages of syphilis, her favorite infectious disease, with anyone willing to listen.

“Even today, when someone starts talking about infectious diseases, my ears perk up,” she stated. “I like the mystery of trying to solve something so complex in a way that can help so many people.”

Gabbidon’s passion for public health stems from her experiences growing up in two countries with distinct cultures. When Gabbidon was ten years old, she moved to the United States, living with her father’s family in Miami until her maternal grandmother arrived from Jamaica. Although at the time Gabbidon thought the move was temporary, she remained in the States, where she encountered stark differences from her home country.

“Living in Jamaica, I never really realized I was Black,” she says. “But in America, I was an immigrant and had an accent. I was clearly different.”

The chasm between Americans who are financially secure and those who aren’t struck Gabbidon as particularly troubling.

Over the years, Gabbidon’s growing interest in social justice drew her towards addressing the structural root causes of health risks for disadvantaged Americans. After receiving her bachelor’s degree from Florida State University, she earned a master’s in public health from USF, focusing on communicable global diseases.

She subsequently received a doctoral degree in health promotion and disease prevention from Florida International University, where she studied the dynamics of sexuality conversations between Haitian and Jamaican parents and their adolescents.

As a postdoctoral research fellow at USF’s St. Petersburg campus, Gabbidon was honored with the University’s Outstanding Black Staff/Faculty Award in 2020 for her teaching and research excellence. Through courses on health psychology, health disparities, and public health, she challenges her students to think critically about their social identities and recognize ways in which they benefit from often unseen privileges.

These conversations aren’t always easy, Gabbidon said, but they’re essential. She uses humor to help disarm students and alleviate their discomfort during these critical discussions.

Gabbidon recently received a $70,000 research grant to target the multiple stigmas surrounding HIV in Tampa Bay, with the goal of increasing health screenings and diminishing the spread of the disease. After some delay due to the coronavirus, the initiative has been transitioned to a virtual format.

“I’m excited to get folks in the community involved with this research,” Gabbidon said. “To me, it’s their project at the end of the day. Some people say we’re giving a voice to the voiceless, but these members of the community already have a voice. We’re just giving them the space to speak.”