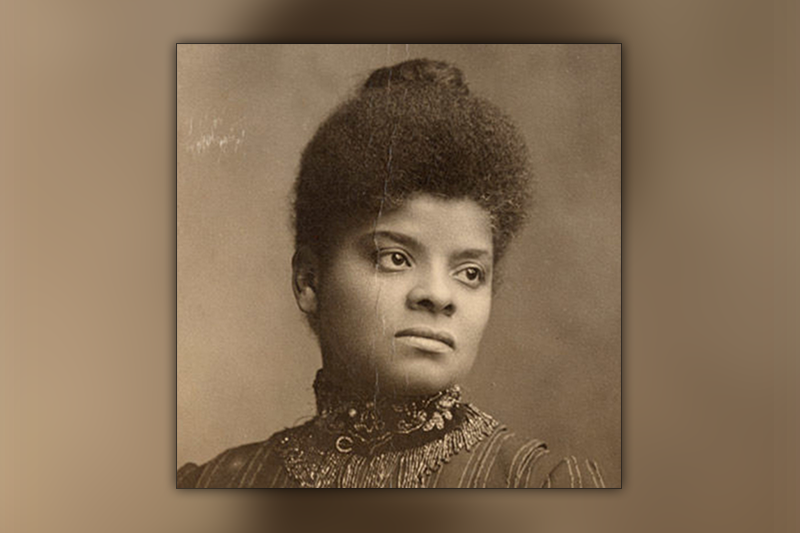

Ida B. Wells was an African American journalist and activist who led an anti-lynching crusade in the United States in the 1890s.

By Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard, President, ASALH

Ida B. Wells was born a slave in 1862 in Holly Springs, Miss. She attended Fisk University in Nashville. She is considered one of the greatest political reformers of the first quarter of the last century.

No other black leader, male or female, took on the issue of lynching black people as she did. She condemned lynchings in two newspapers she owned, writing to reveal the abuse and racial violence African Americans had to endure.

The Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), located in Selma, Ala., recently concluded that nearly 4,500 African Americans were lynched from the end of Reconstruction to 1950. Black men, and sometimes women, were hung from trees with rope around their necks, from scaffolds, and from railroad tracks.

Some were beaten, maimed, cut and burned alive while hung. Many were public spectacles, advertised in local newspapers as to the time and location of the lynchings. Most were without any real evidence of any actual crime having been committed. Black men were often convicted of rape, solely on the word of a white female, arrested, taken from jail, and lynched.

As EJI aptly stated: “African Americans living in the South during this era were terrorized (by lynching) if they intentionally or accidentally violated any social more defined by any white person.”

This reign of terror was legitimized by those whites in positions of power. According to EJI, black “subjugation was to be achieved through any means necessary, and whites who undertook the duty of carrying out lynchings would face no legal repercussions.”

During the period from 1877 to 1950, Florida has been documented to have perpetrated 311 lynchings. In looking for relief, African Americans often looked to the black press. Anti-lynching forces gathered around the black press such as the NAACP, anti-lynching freedom fighters, and record keepers such as Wells, T. Thomas Fortune, and Monroe Work, a sociologist at Tuskegee Institute.

Completely engaged in the issue, Wells created her own newspapers: Free Speech and Headlight, in Memphis. She was a co-founder of the Niagara Movement, the precursor of the NAACP.

Because of rumors, she was considered too radical, so she left the NAACP in 1912. She authored a famous anti-lynching pamphlet entitled “Is Rape the ‘Cause’ of Lynching?”

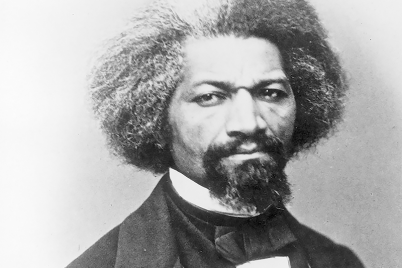

So great was her stature that Frederick Douglass wrote of her in 1885:

“Brave woman! You have done your people and mine service which can neither be weighed nor measured. If American conscience were only half alive, if the American church and clergy were only half Christianized, if American moral sensibility were not hardened by persistent infliction of outrage and crime against colored people, a scream of horror, shame, and indignation would rise to Heaven wherever your pamphlet shall be read.”

A close friend of hers, Thomas Moss, was lynched with two others in Memphis on March 9, 1892, after much violence was perpetrated on the black community. Wells led a series of successful anti-lynching actions in Memphis prior to the violence including a boycott of city streetcars.

In retaliation, her newspaper building was burned to the ground, and after threats on her life and others, she relocated to the North. She moved at first to New York and continued her anti-lynching activities, publishing “A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States.”

The first of its kind, she sought to demystify the often told, untrue rationale for the lynching of black men: they preyed upon white women. Much anger greeted the book’s publication by an outraged white population.

Wells left America in 1893 and went to England to continue her anti-lynching crusade. In 1895, she married Ferdinand Barnett, a Chicago lawyer, and had four children. She continued her activism throughout her life and died on March 25, 1931.

Attorney Jacqueline Hubbard graduated from the Boston University Law School. She is currently the president of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History, Inc.