Hillary Van Dyke explores the complicated relationship African Americans have with water in her documentary ‘A Splash of Color: Getting Black in the Water.’

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG — In her documentary “A Splash of Color: Getting Black in the Water,” Hillary Van Dyke explores the complicated history African Americans have had with water and the current movement to see them participating in outdoor activities more.

As an adventure curator at the Get Black Outside (GBO) organization, Van Dyke believes it’s essential to get people into an outdoor environment for a variety of reasons.

“Firstly, I just think if you are out there, you tend to appreciate it more,” said the film’s writer and director, “and when you appreciate it, you care about what happens to it,” adding that “outdoorsy” doesn’t necessarily mean climbing mountains or kayaking, but merely fishing off a pier or even playing basketball.

Van Dyke began to appreciate spending time outdoors at a young age during family camping trips, which included kayaking, canoeing, biking and horseback riding. Her parents both had green thumbs and spent much of their time outside on weekends tending to their garden.

“I was outside all the time as a kid,” she recalled, “riding my bike, rollerblading, and then I worked for five summers at a girl’s summer camp where I got really into more water sports.”

GBO is a global platform designed to acknowledge, support, and unite black-led grassroots organizations and facilitators that bring outdoor programming to black audiences.

Andre Sesler, a participant of GBO along with his family, said that such organizations create opportunities for Black people to participate in events — activities that we otherwise wouldn’t partake in.

“We’ve over the years expressed an interest as a family of getting outside and going camping, for instance,” he said. “Well, Get Black Outside facilitated those activities to make it seamless for us to show up and become fully engulfed in all the activities that they’ve planned for us.”

Sesler’s wife Krystal said the experiences her children enjoy in activities like snorkeling, kayaking, hiking on nature trails, bird watching and sleeping in tents are priceless.

Van Dyke shared that having recreational experiences with people that look like you are important, where you can “exist with already having these shortcuts to understanding without having to explain why a comment might have been offensive. Without having to defend your expertise, without having unsolicited advice thrown your way all the time.”

Rhonda Bartholomew, another participant of GBO, explained that the organization helped her enjoy the outdoors more because it made her feel comfortable to be around other Black people.

Justin Lovett founded the Unicorns of Diving, an organization for Black scuba divers and snorkelers, to inspire African Americans to not just get in the water but under the water.

“Going on a dive trip with a buddy, we realized we were getting a lot of stares,” Lovett recalled. “A lot of people looking and wondering, you know, why is it that they see not one but two African-American scuba divers? And my buddy and I just came to the realization that we’re unicorns! We’re something that people don’t see every day.”

Chris Clark, a member of Unicorns of Diving, is an advanced rescue diver on his way to obtaining his instructor’s certification to teach diving himself. He explained that he stood out amongst groups of white divers and noted the difference in a group like the Unicorns.

“Being with people who look like you, who have experienced the same things that you have experienced,” he said, “whether it’s how they were raised, the things that they go through in everyday life — it’s soothing.”

As there is an inherent risk in scuba diving, Clark said it helps to put everybody in a mentally safe place first. Tarissa Williams, another member of Unicorns, is also a volunteer diver at the Florida Aquarium in Tampa. She said she learned to overcome her fear of scuba diving by repetition.

“The more often that I got into different bodies of water, from springs to lakes to the ocean, shore diving, boat diving, repetition,” she said. “I grew to love the different types of water and the different ways I was getting into the water and loving everything I found under the water! It took away the anxiety and the fear and only left behind the excitement and wonder for what new things I was going to see when I got there.”

Jason Thompson, another member of Unicorns and GBO, said with the encouragement of these organizations, he is doing things he never thought he would do. He would like to see more minorities get involved in water activities.

Visual artist Vivia Barron created a series of paintings of Black people enjoying the beach and the water.

Vivia Barron is a Jamaican-born visual artist who creates paintings of Black joy and the deep connections Black people have with water.

“That’s motivated by the fact that I am from Jamaica, and I was surrounded by water growing up,” she said. “It’s a big part of my life. I moved to Florida, and I’m surrounded by water as well. For me, there was a gap in us being represented in those spaces, and it motivated me to create works showing us enjoying the beach and the water in a joyful way.”

Kymbriell Finch, a water safety advocate, founded Courageous Leap, whose mission is to “reconnect humans to life before fear through swim lessons and partnerships.”

“I believe that through swim lessons, we are able to learn what it means to be courageous by putting yourself in an environment that’s not so comfortable to you,” she said, “Learning how to survive and thrive in that environment, I feel like that’s a mindset thing and if you can do that in the pool, you can do it anywhere.”

Kimberly Crawford, retired swim instructor, and Finch’s mother said swimming teaches children independence.

“Usually, they have to rely on someone to hold them up in the water, to help them to get to the side, but as they learn to swim, they develop an independence that can travel with them throughout their life.”

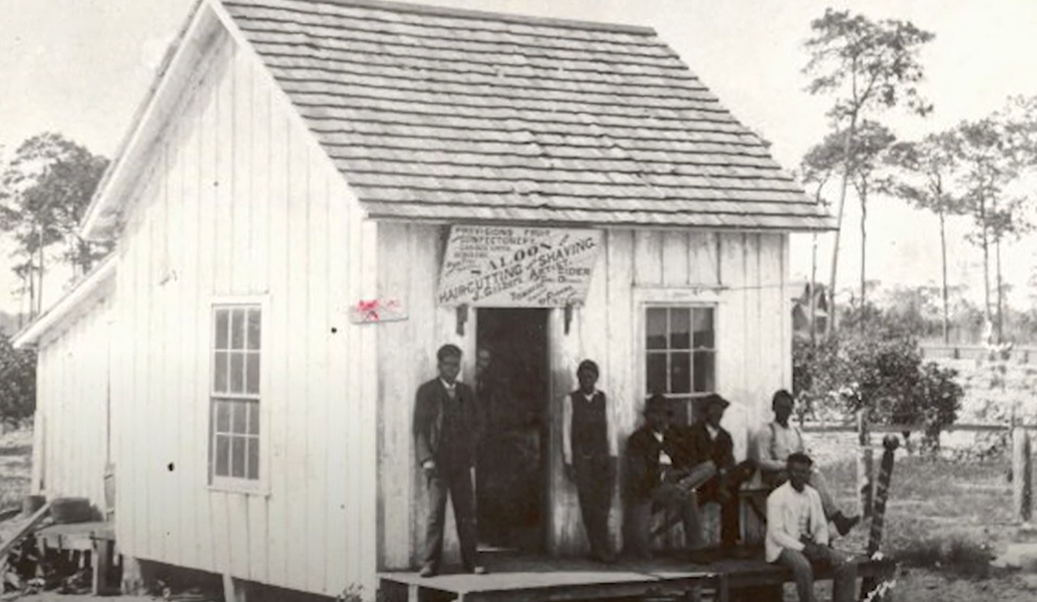

“A Splash of Color” delves into local Black history as Van Dyke noted the connection between African Americans and the water, including the Bahamian sponge diving industry in Tarpon Springs, which preceded the Greek divers.

In the 1890s, a number of sponge divers arrived in Tarpon Springs from the Bahamas to harvest and prepare the wealth of sponges found in the Gulf of Mexico at the mouth of the Anclote River.

“Historically, African people were people who got out into the water,” she said. “They did surf, they did fish … but now we really associate water with the trans-Atlantic slave trade, closed swimming pools during Jim Crow segregation, so I think this work really takes back that narrative to some extent and allows Black people to get away from the ways we’ve been convinced that we don’t like water.”

When organizing swim lessons, Van Dyke makes sure to tie in the area’s history, such as Spa Pool and Beach in St. Pete, a segregated area and focal point of the local Civil Rights Movement. After its integration in 1959, North Shore Pool opened as a landing for white flight.

Finch, a water safety and drowning prevention specialist at the Jennie Hall Pool in south St. Pete, explained that the pool came into being in 1954 when Hall, a white retiree, demanded the city make progress on a pool that African Americans could enjoy, as there were no such pools at the time. She gave the city $25,000 to make it happen.

“We have completely revitalized the community when it comes to their relationship with that aquatic space,” said Finch, crediting the many community elders who helped make it possible, such as Norvell Fuller and Shirley Hayes-Smith. She believes Hall would be proud of the work they’re accomplishing.

City Councilmember Bro. John Muhammad discusses the benefits of water bodies like Clam Bayou Nature Preserve, which runs through his district. Clam Bayou is used for recreation and stormwater runoff that can prevent flooding.

When speaking with people in his district, Councilmember Bro. John Muhammad said their concerns are housing, jobs and public safety, not pollution.

Williams noted that studies show it is psychologically beneficial to be in the water, as it reduces stress.

“Being out in nature, being in the water, it helps in a world where everything moves so fast to help us to re-ground and re-center ourselves,” she said.

Barron pointed out that when she even paints water, she feels grounded and connected.

“I live in Florida, and so I’m painting this water, and I’m connected to Florida in this way,” she said, attesting to the healing power of water.

Krystal Sesler said being near water is relaxing for her as she loves taking her two young girls to the beach at sunset to watch the dolphins come out, and her husband Andre said their family experiences on the waterways give him time to unwind. Lovett said he loves the calming seclusion of being able to hear his own thoughts and even his heartbeat while in the water.

The 40-minute film touches on water pollution and how it affects water activities. Andre Sesler said one of his family’s favorite pastimes is fishing. If pollution directly impacts the fish population, it decreases his family’s opportunities to enjoy the pastime together. Clark noted that pollution tends to stimulate overgrowth in the ocean, and an increase in algae can block sunlight to the reef.

Justin Lovett (above) founded the Unicorns of Diving, an organization for Black scuba divers and snorkelers.

Muhammad admitted that though the water pollution issue is crucial, it does not rank high in importance for many constituents he talks to. When speaking with people in his district, their concerns are housing, jobs, and public safety.

Finch, who is also the founder of Swim with Kym, said many in the Black community are just trying to survive.

“We don’t have the luxury of going out and experiencing boating and kayaking and the sea trek experience on the beach,” she explained, adding that many youths in south St. Pete, which is at the tip of a peninsula, have never experienced the beach.

“It’s important for us to remember that protecting people and protecting nature are not at odds,” Van Dyke said, noting that often “when a space is exploited, you’ll find that the people in that space are also exploited.”

Muhammad said the government should do a better job of promoting the waterways and sharing with the community.

“When you listen to people who are excluded from these spaces,” Van Dyke said, “you will learn ways to help them feel more included and to open access, but I also think when you open access to them, you’re really going to help open access to all sorts of communities that maybe you wouldn’t have realized were being excluded unintentionally.”

Van Dyke visualizes a day when Black folks can be outside doing things “without it being weird or being an exception.”

“When they can go to a hiking trail and not have to deal with people asking if they’re part of a church group or a family reunion,” she said. “Where they see people who look like them who aren’t with them on the trail, and we just normalize the idea that we belong in these spaces, and it isn’t weird when we are.”

Van Dyke produced “A Splash of Color” as a part of her work as an alliance member of BlueGAP, with funding support from the National Science Foundation Convergence Accelerator. She worked closely with Ryan Watson of WatsTower Films and Maya Burke of the Tampa Bay Estuary Program.

The film debuted at the Warehouse Arts District on Jan. 6 to an enthusiastic crowd. The next screening will be on April 18 at the Foundation for a Healthy St. Petersburg. For more information, visit instagram.com/asplashofcolorfilm