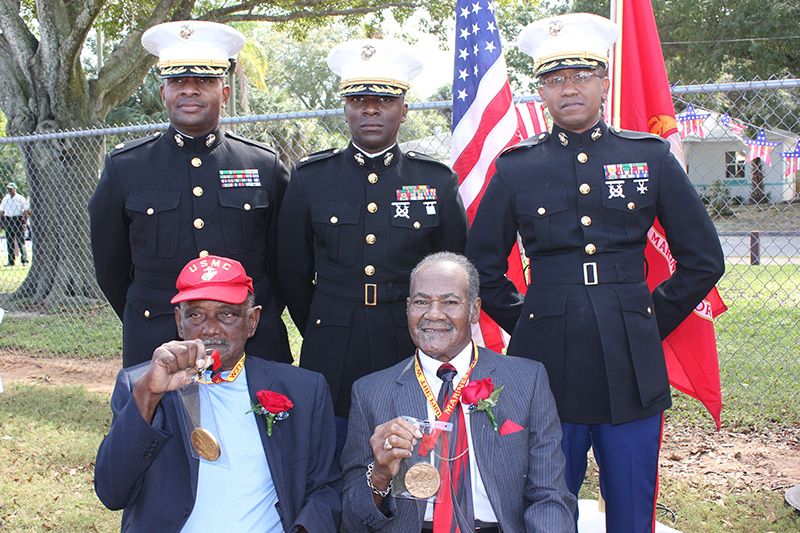

William C. Scott, left, John Tyrone Ayers and Samuel L. Blossom (deceased) were honored with the Congressional Gold Medal Fri., Nov. 8, at Wildwood Recreation Center.

BY HOLLY KESTENIS | Staff Writer

ST. PETERSBURG – William C. Scott is a marine, a Montford Point Marine. And when he walked into the St. Petersburg Housing and Community Development office last year, he had no idea that this distinction would open the doors to a rehabbed home and a medal for distinguished service. — a medal that has been a long time coming.

Linda Byars was working the day Mr. Scott dropped by to find out if he could get assistance repairing his roof. Wearing his red United States Marine Corps cap, he got her attention.

“I think the first thing he said to me was, ‘I’m a U.S. Marine,’” Byars said.

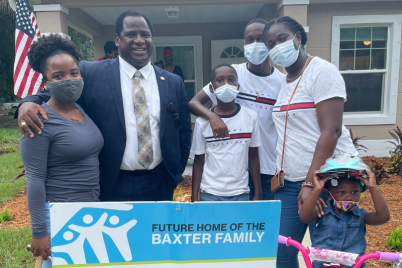

Left, Aaron Williams, Councilmember Wengay Newton, William C. Scott, and John Tyrone Ayers

When he left, she looked him up and realized he was not only a marine but part of the original Montford Point Marines, the first black unit of the U.S. Marines Corps. “I did my research,” Byars continued, “and I said, this is history.”

So along with city officials and a community of volunteers willing to donate their time and money, she set out to complete the necessary paperwork so that Mr. Scott, who served in World War II, the Korean War, and Vietnam, could get his new roof. But when the inspector showed up, it turns out his situation was more dire than what he was letting on.

Not only did the roof need to be repaired, but the entire roof structure. Conditions were so bad that building officials would not allow him to return to his house until the necessary repairs were made.

“We scrambled about and came up with a little money,” Byars said.

With thousands of dollars in repairs either found or donated, volunteers helped move Mr. Scott out of his home back in May so they could fix the dilapidated roof and make other improvements to the home. Mold was eating away at its interior, and he had been without running water or electricity.

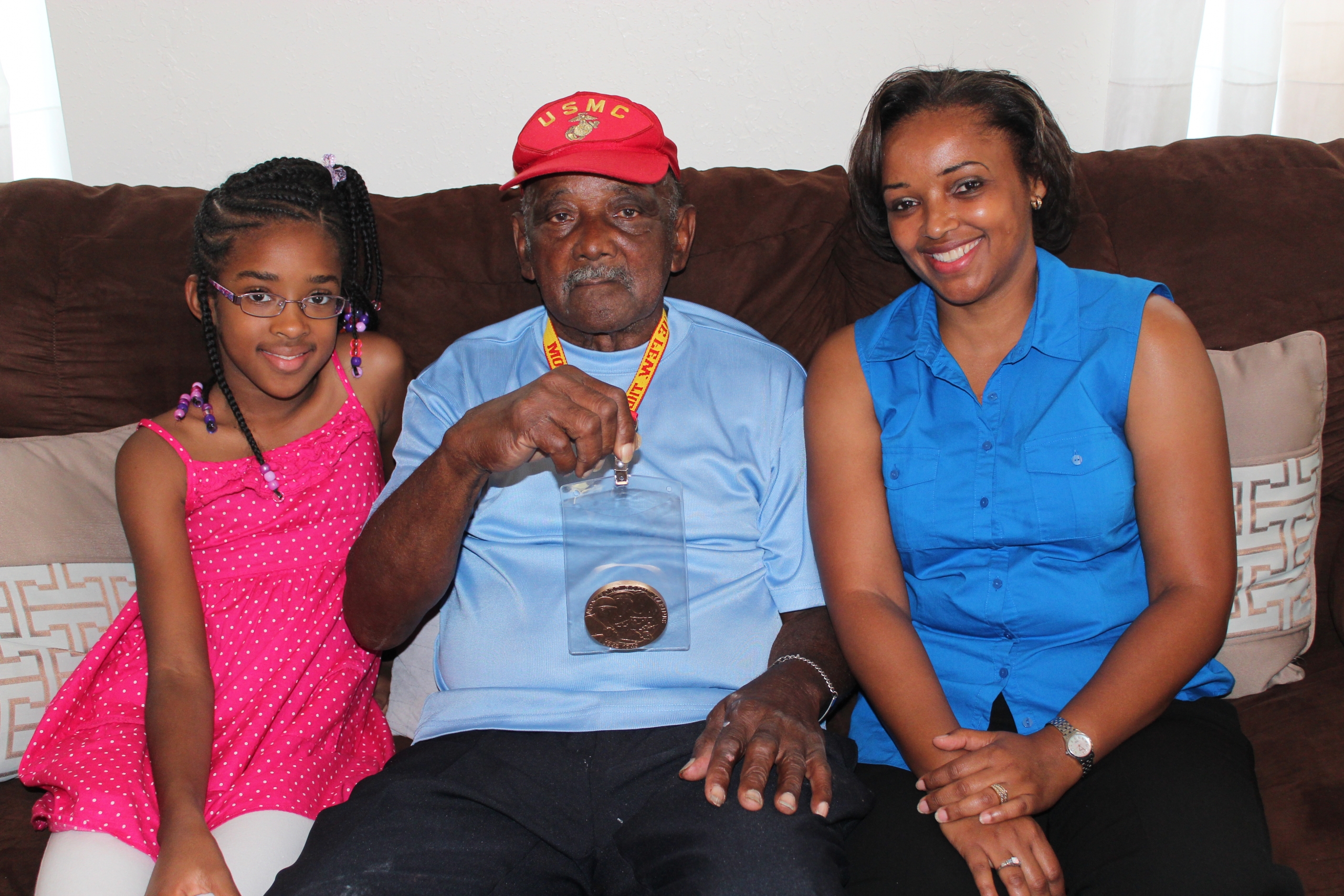

Daughter Brigette Morton flew in for the special occasion and was delighted at all the attention being thrown her father’s way. A humble man that some close friends would even call ornery, Mr. Scott usually shies away from attention. Preferring instead to serve his community rather than be the main attraction. But at 87, the Montford Marine is learning to let others in and accept assistance.

L-R, Benia Morton with her grandfather William Scott and mother Brigette Morton

“He doesn’t like all the accolades,” Morton said, speaking of his strong will. “It was amazing to see his level of receptiveness to what everybody was able to do for him because he resists help.”

Although overwhelmed with gratitude, the tears didn’t start flowing until the early Veteran’s Day observance ceremony on Friday was underway across the street from his home at the Wildwood Park baseball field.

William C. Scott and John Tyrone Ayers were finally awarded the Congressional Gold Medal for their participation in World War II.

Back in 1942, President Roosevelt gave African Americans an opportunity to be recruited into the Marine Corps. Approximately 20,000 African-American recruits signed up during the next seven years to fight in World War II. All along, the intent is to return them to civilian life after the war was over and leaving the Marine Corps an all-white organization. Segregated from their white counterparts, troops were sent to Montford Point, located at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, to receive their basic training.

But attitudes changed, and when reality set in and the war progressed, it became evident that black marines were just as capable as any other marine. So in 1948, then-President Harry S. Truman issued an executive order to negate segregation, thus deactivating the Montford Marine Camp.

Mimi Ayers with her father, John Ayers

As recently as last year, more than 400 African-American alumni of Montford Point were honored for their service in the military during World War II. They were presented with the nation’s highest civilian honor, the Congressional Gold Medal. But Mr. Scott and two of his brethren, Mr. Samuel L. Blossom (now deceased) and Mr. John Tyrone Ayers, did not receive their honor. Although the Marine Corps became determined to acknowledge each marine who served at Montford Point, some were obviously missed.

Family of Samuel Blossom

But with a bit of persistence and many follow-ups, the City of St. Petersburg stepped up and rectified the oversight.

“It’s been a long time,” Mr. Scott said, speaking of the shiny medal hanging around his neck and trying to find the right words to describe his feelings of being recognized for his service after all these years. “It feels good.”

As it should, however, Mr. Scott hasn’t forgotten those long-ago days. With the segregated boot camp and the all-black units that ensued after training, it was evident to the African-American men enlisted that the country wanted their services to win a war but didn’t want to allow them their freedoms. Some encountered racism, many telling of being refused services or having to sit in special rail cars reserved for black soldiers.

“I’ve heard the horror stories,” Morton revealed, speaking of the social and racial turmoil her father endured. “So to see him sitting there with that medal and the look of joy on his face, that is very moving, and it means a lot. It was a long time coming.”

Richard D. Marshall of the United States Marine Corps was on hand to present the awards and recognize each of the three veterans for their fighting spirit. Gibbs High School Honor Guard and the Veterans of Foreign Wars (VFW) were also in attendance to present the colors.

So, with a medal and a rehabbed house all before noon, it definitely was a good day for Mr. Scott.

“I have heard many times that love is not what love says but what love does, and I see it in the faces all around me,” Mr. Scott concluded as he invited everyone to take a look at his new digs.

Loans used in refurbishing Mr. Scott’s house were made available with state and federal funding from the state housing trust fund. Donations were provided by Home Depot, Badcock Furniture, Scott Paint, Yutzy Tree Service, and Ken Dye Lawns, Inc. Beall’s Outlet, Habitat for Humanity of Pinellas, and E-Construction Group, Inc. also took part in providing services for Mr. Scott’s new home.