The 2023 BurGala held at the University of South Florida St. Petersburg Campus celebrated diversity, inclusion and members of the community who help eradicate racism.

BY FRANK DROUZAS | Staff Writer

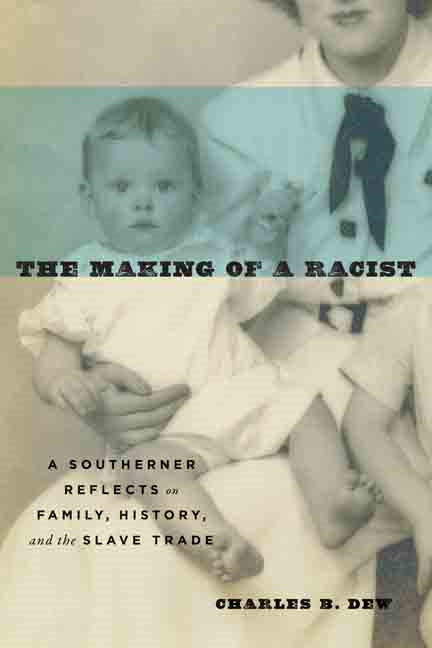

ST. PETERSBURG — RaceWithoutism, Inc. presented BurGala 2023 on Dec. 2, an event to celebrate and promote diversity and inclusion. The evening featured special guest Dr. Charles B. Dew, who discussed his book “The Making of a Racist: A Southerner Reflects on Family, History, and the Slave Trade.”

Danny E. White, president of RaceWihtoutism, Inc., explained that his organization is about unity and “people seeing people for who they are, not skin tone.” Through sponsored events such as BurGala, it promotes open and honest conversations that aim to get at the root cause of racism.

Mayor Ken Welch said that celebrating inclusion will move our community forward.

“In St. Pete, we believe in equity and inclusion, and we understand the power of that,” he said. “We understand what history means when we look at something like the historic Gas Plant and why that needs to be approached in the spirit of equity and promises that were made 40 years ago.”

Television and film writer, director, and producer Erica Sutherlin served as mistress of ceremony and noted that the event featured its first annual Leadership In Forging Transformation (LIFT) Awards. Winners of this year’s awards included Carla Bristol, St. Pete Youth Farm, Antonio Brown, Barbershop Book Club, and Dr. LaDonna Butler, The Well for Life, Renee Edwards-Perry, Saturday Shoppes and historian Josette Green, St. Pete Black History Bike Tour.

White presented the awards and lauded each winner for their contributions to the community. In praising Bristol, he said of her unique youth-led urban farm, “It’s more than just a place to put your hands in the dirt.” The St. Pete Youth Farm has turned six empty city-owned lots into a place to grow fruits and vegetables and minds.

Carla Bristol received the LIFT Award for her commitment to ‘lifting’ youth in our community by helping them learn valuable life skills, teamwork and respect for themselves and Mother Earth.

“We are in every aspect of the food system,” Bristol said, “so we would like you to know your city — our City of St. Petersburg — has something that’s incredible, and we invite you to come visit it.”

Antonio Brown received the LIFT Award for ‘lifting’ our youth by showing them the wonders of reading, thereby contributing to improved literacy among the youth in the community.

Brown thanked everyone for celebrating the effort and compassion he has put into his Barbershop Book Club, which promotes literacy for at-risk children while they get haircuts.

“The barbershop has been a cornerstone of our communities since the beginning of time,” said the master barber. He notes that after working in several shops and ultimately owning his own, he realized the positive influence barbers can have in their communities.

Standing with Danny E. White, Dr. LaDonna Butler received the LIFT Award for ‘lifting’ the spirits, minds, bodies, and souls of those who need a mental helping hand.

Dr. LaDonna Butler co-founded her nonprofit The Well for Life, which started as a mental health practice but has grown into an organization that provides communal healing spaces.

“On behalf of The Well, which was established as a place for my own healing, I know that it is through efforts like RaceWithoutIsm that recognizes the work that we do that is only going to push us further together as a community,” she said.

Renee Edwards-Perry received the LIFT Award for ‘lifting’ people to higher heights through collaborative strategies that ultimately transform lives.

The vision behind Saturday Shoppes, founded by Edwards-Perry, is to create economic development opportunities for emerging businesses through monthly markets while promoting diversity.

Edwards-Perry explained that she started Saturday Shoppes, which operates in various locations in Tampa Bay and even Atlanta, two years ago, and its number of vendors has exploded since.

“We’ve grown from 64 vendors to now we have 1,700 minority-and women-owned businesses coming down,” she said.

Josette Green, standing with Danny E. White, received the LIFT Award for ‘lifting’ and highlighting the rich Black history of our city and for doing the right thing for the right reasons.

Green is the founder of the St. Petersburg Black History Bike Tour, which takes participants to the actual locations where history began for St. Pete’s Black residents and reveals an understanding of the systemic racism in our city today. So far, the bike tour has completed 50 tours with almost 800 people.

“I want you to know that it’s not just about learning the history but understanding the impact today on our city,” she said. “And all these folks are given action items, so we have almost 800 people out there that know the value of supporting Black-owned businesses, that know the value of looking at the demographics and salaries of their employer and their work situation. So, they’re giving several action items to go out in the world–and that’s what makes the difference to me. It’s not just about telling the history but taking that information out in the world today and making a difference for racial equity.”

Dew, a St. Pete native and retired professor, taught American history, the history of the South and the Civil War and Reconstruction at Williams College in Williamstown, Mass. In discussing his 2016 work “The Making of a Racist,” Dew noted that “racists are made, not born.” People embrace pernicious ideas of white supremacy as they grow up in certain parts of town, he said, which was his experience in St. Pete. Growing up in the 1940s and 1950s, he viewed firsthand how white and Black people interacted with one another.

“I never saw my mother or my father shake hands with a person of color,” Dew said. “That was a violation of that etiquette that governed the way whites and Blacks interacted with each other.”

Dew explained that conversations between people of different races could be about the weather, baseball, or anything else at all, provided they would never approach anything like social justice. Dew, who, as a youth, saw a clear color line and assumed it was there for a reason, even believed for a time that racism was biogenetic.

When he was 14, Dew recalled his successful lawyer father giving him a book titled “Facts the Historians Leave Out: The Youth’s Confederate Primer.” Unsurprisingly, it spun history in its own skewed way, maintaining that most of the enslaved were treated well and were happy in a kind of “security system” where white folks took care of Black folks, Dew explained. The stereotype promoted in this book was of the “sambo,” a not-very-bright manchild who is happy-go-lucky “more interested in a good time than hard work,” and this sort of spurious information was what Dew absorbed in his impressionable years.

As a freshman arriving at Williams College, Dew recalled telling a “Rastus and Lulabelle” kind of Black dialect joke in his dorm that he knew from growing up in his household. At that moment, an African-American student walked by his open door.

“I saw him, and I froze,” Dew said, “and I felt that I had humiliated myself, and I believe that I had humiliated him.”

The following day, while headed to breakfast, Dew found the student, introduced himself, and offered his hand, which the African-American student accepted.

“I shook hands across the color line for the first time as a 17-year-old,” Dew remembered. “He became a friend, and my education at Williams College began before I walked into my first classroom.”

Dew’s father, Jack, believed in segregation full-heartedly and even flew into a “volcanic rage” when Bill Williams, an African American who ran a shoeshine parlor, attempted to visit the elder Dew to apologize for a disagreement they’d had — all because he’d failed to use the back entrance.

“Bill had committed the cardinal sin of approaching our house through the wrong door,” Dew said. “He did not come to the back door; he came to the side door.”

If you grew up on the white side of the color line, Dew explained, you can be looking at a grotesque abomination of a social structure that “humiliates people on a daily basis; you can be looking at it, and never see it.”

After obtaining his driver’s license, Dew began driving his family’s housekeeper, Illinois Browning Culver, home so she wouldn’t have to take the bus. One day, he mentioned that he was sorry that her son Roosevelt had to leave St. Pete because he couldn’t go far there due to his skin color.

“She looked at me and was silent for a long time,” Dew recalled. “She was making up her mind if she could trust me. This was dangerous territory. You didn’t talk about this stuff. Finally, she said, ‘Yes, Charles, it is a shame he had to leave,’ and that opened up a whole world of conversation and realization to me.”

Browning Culver began to confide in Dew more, and in giving him glimpses of what daily life was like for people of her color, Dew received a valuable education. For example, she told him that she could go to a department store and pay for a dress but could not try it on in the store, as that was never permitted for Black patrons. If the item of clothing didn’t fit, Black people had to take it to a tailor for alterations.

She told him that St. Pete’s famous green benches were segregated, which was news to Dew at the time. Browning Culver was a big fan of The Price Is Right show, and when Dew asked her why, she said it was the only show that had “colored folks on as guests.”

One day, when they were discussing race-based restrictions and conventions, such as black and white people not shaking hands, Dew told Browning Culver he didn’t know where it all came from.

“She looked over at me, and she was almost in tears,” Dew said, “and she said, ‘Charles, why do the grownups put so much hate in their children?'”

If a person decides they are on one side of the line and everyone else with specific characteristics is the “other,” then it is easy to denigrate and be bigoted toward that “other,” Dew pointed out.

“If things aren’t going so well in your life, it’s frequently the case that you blame the ‘other’ with what’s going wrong with your side,” he said. “I think there’s too much of that in our politics today.”

The evening ended with celebrating the rhythms of the African diaspora as the crowd vibed and swayed to demonstrations of dance that borrowed from Afro beats that created the unique sounds found in cultures from Africa to Spain to the Caribbean to Brazil and the United States.